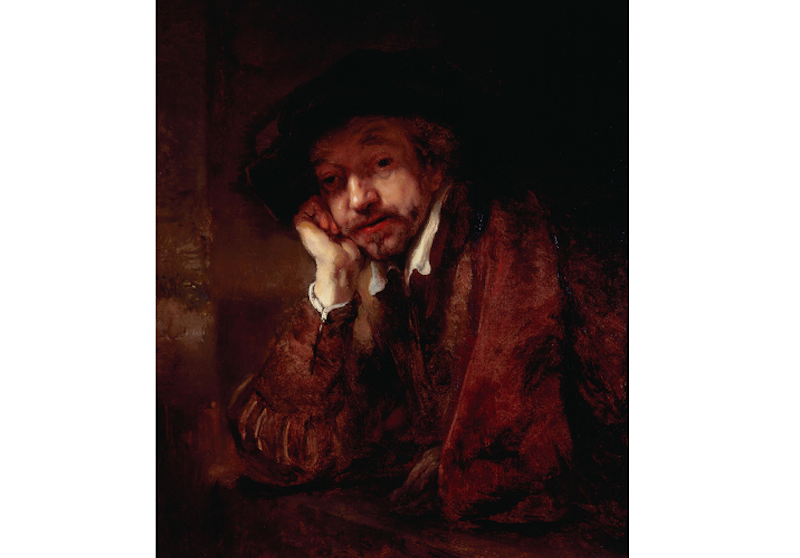

Photo: Provided by Taft Museum of Art

Imitator of Rembrandt van Rijn (Dutch, 1606–1669), Man Leaning on a Windowsill, probably early 1700s, oil on canvas. Taft Museum of Art, Bequest of Louise Taft Semple, 1962.1

Generally when visiting a museum or art gallery, the authenticity of what’s on view isn’t in question. When we read labels or captions assigned to works of art we believe what we see, because why wouldn’t we? The scholarship involved in verifying art has evolved to an almost exact science. Professionals even can tell how a canvas was prepped in hundred-years-old paintings.

But they can’t get it right all the time.

An upcoming exhibition at the Taft Museum of Art will display and examine rare instances of art that was once thought to be original, authentic in a certain way or attributed to a specific artist, but was found to be something else entirely. Fakes, Forgeries, and Followers opens Oct. 22 and runs through Feb. 5 in the Sinton Gallery at the Taft Museum of Art.

“We had just finished a complete, pretty extensive reinterpretation of works in our permanent collection for the reopening of our historic house, which happened in June,” says Tamera Lenz Muente, Taft Museum of Art curator. “We were just thinking about other exhibitions that we could do related to our permanent collection. We thought it might be interesting to people if we were to pull those works out of storage, which are rarely seen, and share the stories behind them to kind of share the science that goes into determining what works are not authentic.”

Muente says many of the works in storage are there because of their de-authenticated status – some of which haven’t been seen by the public in 30 years. Of the 800-plus works in the museum’s collection, only about 14 have been given such a status, which doesn’t necessarily render them useless, unattractive or less valuable. In fact, the Taft is seizing it as an opportunity to educate by putting these works on display and publicizing the journey that solved their mysterious origins.

“In our mind, they are great educational tools for people to be able to learn about how things were determined,” Muente says. “I think it can also teach you about the real thing by looking at the thing that is not real.”

Among the pieces are paintings, decorative works of art and furniture. A number of works were bequeathed by the Taft family, who lived in the historic house in the late 1800s. An armoire owned by Charles Phelps Taft, half-brother of former President William Howard Taft, is a prominent and ornate piece in the exhibition. Included in the display will be an excerpt from a letter Charles Phelps Taft penned to President Taft, describing his experience in an antique shop in Paris, where he found the piece of furniture.

In part, the letter says, “I think it would amuse you to see your brother rummaging round in these old antiquaries’ shops trying to pick up works of art.”

Muente says the armoire is possibly the biggest piece of furniture in the museum's entire collection. It was believed to have been made during the Renaissance until a closer examination determined it was made in the 1800s as a Renaissance Revival piece.

Kiosks and labels throughout the exhibition will share information about methods used to authenticate and date works of art. Raman spectroscopy, for example, is a technique scientists and historians apply to paintings. It scans paint surfaces to determine what minerals or elements make up the pigments.

This information is especially helpful when dating pieces because of certain elements’ presence that may not have been invented when the work was believed to be created, Muente says. This method was employed on certain pieces included in the exhibition. It has even been used to re-authenticate certain works. Other methods include radiography, infrared photography, microscopic examination and in-depth comparisons with genuine works.

Fakes, Forgeries, and Followers in the Taft Collection also will highlight the distinction between categories of deauthentication. While it might be simple to understand that a work was determined to have been painted by an artists’ follower instead of the actual artist, it could be a little more tedious to differentiate fake and forgery.

“In my mind a forgery is something that, from its inception, was created to deceive,” Muente says. “To intentionally deceive, that would be a forgery. A fake, that kind of runs the gamut."

"So, take the work of Rembrandt for instance," Muente continues. " There are two paintings in the show that were once believed to be by him. One is now known to be by a follower of Rembrandt, which means it was likely someone who was his student or worked in his workshop or was an admirer in his circle who emulated his style but did not necessarily intend to deceive in that way.”

Muente says Rembrandt’s work became so popular, a lot of his followers' pieces have been misinterpreted to be original. In 1968, the Rembrandt Research Project was founded by the Netherlands Organization for Scientific Research to categorize and organize the multitude of works circulating believed to be by Rembrandt. The project lasted for more than 40 years and helped classify Man Leaning on a Windowsill – a painting endowed to the Taft by Louise Taft Semple in 1962 – as either an imitation or a deliberate forgery.

The Taft Museum of Art is located at 316 Pike St. General admission includes access to Fakes, Forgeries, and Followers in the Taft Collection (Oct. 22–Feb. 5, 2023) as well as the museum’s permanent collection galleries located in the Taft historic house.

Stay connected with CityBeat. Subscribe to our newsletters, and follow us on Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, Google News, Apple News and Reddit.

Send CityBeat a news or story tip or submit a calendar event.