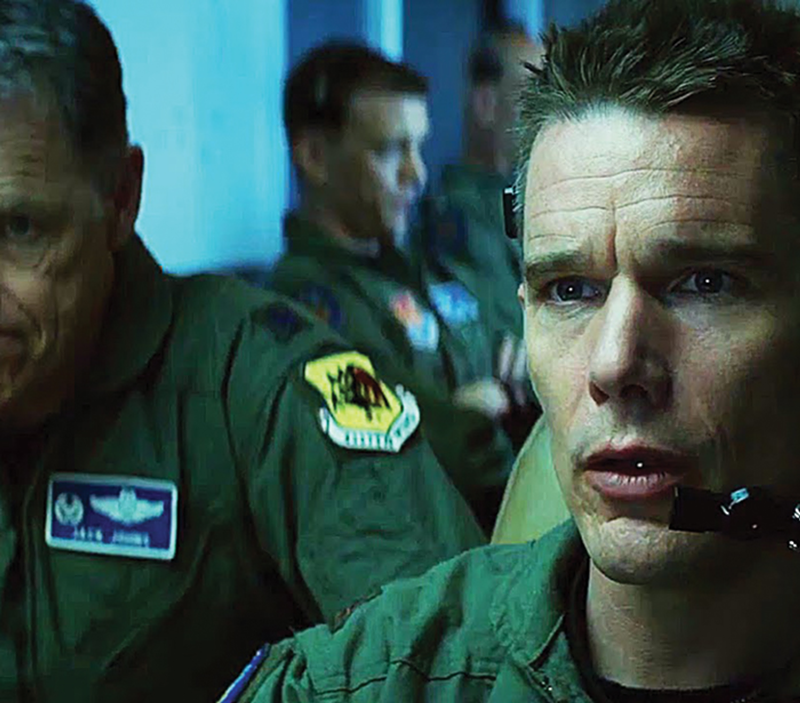

This isn’t real life, Good Kill, this new movie from writer-director Andrew Niccol (Gattaca, Lord of War), about Major Thomas Egan (Ethan Hawke), a long-serving and highly decorated pilot who now “flies” drone missions from a trailer in the Nevada desert and bombs targets in the Middle East.

Egan, from time to time, reminds various characters (and the audience) that he served several tours in the actual hot zone, logging his hours in the cockpit up in the not-so-friendly skies before settling down in this mission that allows him to do his dark business and then head home to his beautiful wife Molly (January Jones) and their two kids.

It must be better to be home, to be able to pick up the kids after school, to attend soccer games, to have sex with the wife, to drink away the memories of all those good kills that he and his crew are still able to rack up, right?

Niccol wants desperately for us to believe this is real, just like the military wants these pilots, these drone warriors, to appreciate the harsh reality of what they are doing. These missions are more than just “surgical strikes,” says Lt. Colonel Jack Johns (Bruce Greenwood). He’s fed up with the euphemistic language — in war, the task at hand is to end life, to kill — and the video game mentality that has replaced the warrior pilot training.

To be a pilot, you ought to actually fly planes, rather than joystick a simulated drone thousands of miles away. There’s no skin in the game anymore — no sense that you could die in the service of your mission (to kill).

I wanted to believe it was real, this movie, because the issue at hand is fraught with all of the necessary ethical and philosophical questions that we as a society should be addressing, rather than picking around the edges, questioning how much war costs us each day or which political party/candidate voted to fight based on faulty intelligence in the first place. Does it matter how we fight, how we kill?

And I suppose I’m also asking if this makes for engaging cinema. That’s certainly the tricky part from an analytic perspective. To plot such a premise means trumping up situations, giving actors things to do with their characters, so far removed from the action.

I was fine with the idea of Egan lobbying to go back into battle. He is modeled on the type of soldier/man that Clint Eastwood gave us in American Sniper. Egan’s pilot is the same type of dead-eyed, by-the-book killer that Chris Kyle was — a loyal man with the steadfast belief that what he was doing was right and good for his country. He would do it 100 out of 100 times the exact same way in those tense moments.

But when you remove him — or any soldier — from the theater of battle, and when you pull the audience away as well, you have to twist us up in knots a bit more by ratcheting up the drama, by compromising the narrative.

It is peculiar, though, because the situation is already compromised enough. We don’t need to see an insurgent repeatedly rape a woman sweeping up an enemy compound, especially not through the eyes of Egan’s new “co-pilot” Airman Vera Suarez (Zoë Kravitz), or witness the team’s transfer of command from the military to the CIA, which is far less rigorous in their delineations of enemy combatants and hot targets.

The debate is worthy and necessary. And the idea of questioning the reel versus the reality, well that’s understandable, but you don’t have to stack the deck. The game, such as it is, happens to be rigged already, weighted against those who would argue against ever going to war, even if we truly still had real skin in the fight.

We’re terrorists now. That is a very real message embedded in the narrative, but what is missing is the sense of outrage, the sheer atrocity of our acts. Maybe that’s why we can still dare to consider these kills “good.”

Of course, when you go back to the question of whether or not this makes for good filmmaking, the burden rests squarely on the shoulders of the performers who must convince us that the dialogue and action (of which there is very little) arises from human characters and press secretaries at the podium or talking heads on cable news sets.

Hawke leads the charge here, living in the skin of a man removed from the cameras and all of the chatter. He is steely-eyed, lasered-in on his target and unseen threats ready to spring up from any and all sides.

It is just too bad that he can’t defend himself from all of the words and ideas that are killing his good efforts. (Opens Friday at the Esquire Theatre) (R) Grade: C+