It’s a fresh, warm Friday morning in early August and I’m deep in “God’s Country” near Petersburg, Ky. The sun shines confidently on small pockets of verdant forest, the air is crisp and every few miles a local farmer is selling summer corn, tomatoes and melon.

Today, however, “God’s Country” has a few strange bedfellows: a congregation of atheists, all gathering at the Creation Museum, the best-known and most controversial monument to Creationist beliefs in the Midwest and perhaps the world.

This 70,000-foot structure offers 160 exhibits that seek to bring the pages of the Bible to life. Its interactive displays allow visitors to see the history of the world as described by the Book of Genesis, that the heavens, the Earth and life were created divinely in seven days.

The museum attempts to merge Biblical texts and modern science to show, among other things, that the Earth is approximately 4,300 years old and dinosaurs and man used to be neighbors.

People have come from as near as Union, Ky., and as far away as Halifax, Nova Scotia, this day to tour what some believe to be a reverent place and what others consider a hoax. More than 300 students, scientists and atheists — people who don’t embrace a god or a religion — are patiently waiting in line for entrance to the museum.

The trip was organized by the Secular Student Alliance (SSA), an educational non-profit group based in Columbus, Ohio. Its mission is to educate college and high school students about the value of scientific reason and the intellectual basis for atheism.

Lyz Lidell, SSA’s senior campus organizer, planned the trip to the Creation Museum because while she had heard reviews of the facility, she didn’t want to make a snap judgment.

“You can’t speak against anything if you don’t know what you’re talking about,” Lidell says.

‘The bottom of the list’

The large turnout at the Creation Museum isn't unusual for southern Ohio. Greater Cincinnati has a burgeoning and thriving atheist community and is responsible for large contributions to both the national and global atheist/secular humanist movements.

The two dominant atheist organizations in the Cincinnati area are The Free Inquiry Group of Greater Cincinnati and Northern Kentucky (FIG) and the Atheist Meetup Group. The local meetup group was established in 2003 and boasts 337 members and has held 144 meetups so far. The FIG group has been in Cincinnati since 1991 and is affiliated with national secular organizations, such as the Council for Secular Humanism, the American Humanist Association and American Atheists.

Joe Levee, 84, of Cincinnati is the founding member of the FIG group and has been an active member for 18 years. He got the idea for the local FIG chapter after visiting the Council for Secular Humanism (CSH) in Amherst, N.Y.

Chapters of the CSH were being established in Washington. D.C., and Levee thought Cincinnati could benefit from an affiliate group.

“I was nervous just because I knew (Cincinnati) was a conservative town,” he says. “But I thought it was important for secular humanists to get together.”

Assisted by the editor of Free Inquiry, the CSH’s monthly magazine, Levee contacted local subscribers and invited them to the first of many FIG meetings. The group meets bi-monthly for discussion and potlucks.

Cincinnati’s political climate has warmed to atheists in recent years, Levee says. That may be due to a nationwide shift in attitudes about religious beliefs. A national poll conducted in March by USA Today found that 15 percent of Americans claim no religion at all. It’s the third largest “religious” category in American after Catholics and Baptists.

That’s a drastic change since 1991, according to Levee. “Most of the polls in those days were about how atheists had less chance of being president than homosexuals,” he says. “(We) were at the bottom of the list.”

A sense of community

Days later, while driving on a long, painfully flat stretch of road, a clear azure sky above, it appears I’m lost and late.

My photographer friend and I are on a pilgrimage to a children’s summer camp on the outskirts of Kalamazoo, Mich. I was due to arrive at noon and the time is nearly 1:15 p.m.

After several wrong turns, I careen down the unpaved, forested path leading to Camp Kindle, the summer home of Camp Quest Michigan, a week-long residential summer camp where children of atheists, secular humanists and freethinkers come to learn about science, philosophy and a sense of community.

Campers show their support for one of their peers as he scales a climbing wall at Camp Quest. Photo by Keith Rutowski

Greater Cincinnati was ground zero for the first atheist summer camp in the United States. The first Camp Quest was held near Cincinnati in 1996. Since then, the camp has sprouted eight legs, six across the United States and two international satellite camps in Canada and Britain.

Camp Quest Ohio had more than 70 campers this summer and Camp Quest Michigan boasted roughly 25, as did Camp Quest England.

Len Zanger, director and founder of Camp Quest Michigan, has been at the camp’s helm since it began in 2003. A design engineer by day, Zanger started the camp to provide the children of atheists with a common ground in which to make friends and socialize without being preached to or harassed.

“That’s our motivation, to see these kids get together and have some community,” Zanger says. “That’s what we do it for.”

When we arrive, the kids have just finished taking a group photo and are getting ready for a swim at the lake. High-pitched squeals can be heard from their bunks as they clamor for bathing gear, each wanting to get to the water’s edge first.

The camp’s activities are similar to any other summer camp, with swimming and outdoor games as the norm. But Camp Quest delves into knowledge-based activities as well. Children learn elemental philosophy, astronomy and critical thinking skills.

“We try to develop kids who are able to think for themselves,” Zanger says.

Camp Quest-ers also are engaged in discussions about critical religious and moral issues. The children deconstruct church doctrine, like the Ten Commandments, and talk about them outside the context of religion.

Zanger likes to discuss logical exceptions to religious instructions with the kids: “If you need to steal a loaf of bread to feed your family because they’re starving, that’s more moral than refraining from stealing,” he says.

A common misconception about Camp Quest is that the camp is place where children go to be converted to atheism or indoctrinated with atheist thought, a charge Zanger denies.

“I’m not sure atheism can be taught,” he adds.

Most of the children at Camp Quest are already growing up in atheistic or freethinking homes and are religion-free by the time they get to camp.

A younger camper, Caitlin, is spending her second summer at Camp Quest. Caitlin, who comes from a secular household, enjoys coming to the camp because it allows her to spend time with like-minded children her own age.

Caitlin chose to be an atheist on her own, she says. “The whole concept of supernatural things and God just seemed kind of unusual and silly,” she adds. “I like to think of things as scientific and logical.”

Other Cincinnati atheists also volunteer at Camp Quest. President of the FIG group John Welte and his wife Fran have been counselors at Camp Quest Michigan the last two summers.

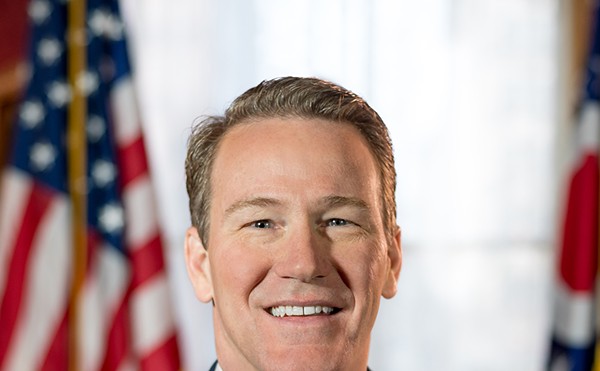

John Welte (Photo by Keith Rutowski)

“There’s a lot of science-type camps … geared towards one particular discipline,” Welte says. “(But) we pretty much cover everything.”

Welte is a staunch advocate of teaching kids about several science disciplines, but believes the ability to think for oneself is the best skill the kids will get.

“I think it helps them to understand how difficult it is to argue a point when your opposition in the argument is totally convinced they’re right,” Welte says.

One of the free-thinking exercises at Camp Quest involves two invisible unicorns that cannot be seen or sensed, but that are believed to reside at camp. The children’s job is to prove the unicorns don’t exist. The winner receives a “godless,” pre-Eisenhower $100 dollar note without the words “In God We Trust.”

Camp Quest’s founder, Edwin Kagin, also is on site. Kagin, 68, and his wife, Helen, of Union, Ky., founded the first Camp Quest along with the FIG group in 1996 as a secular alternative to the Boy Scouts.

Kagin believed children of atheists “needed a place where they could feel safe and comfortable and not persecuted.”

He often sees campers in tears because the sense of community makes them feel like they belong. A young girl told him once that the camp made her feel like it was OK not to believe in God.

This is Camp Quest’s essence.

“We note that she didn’t say ‘I have learned there is no God.’ We don’t teach that,” Kagin says, an important distinction that he feels is often lost.

The Kagins were the directors until their retirement in 2005. This summer, Kagin traveled abroad to participate in the first Camp Quest England.

“It looks as if Camp Quest has reached what I call a ‘critical mass,’ ” he says. “It’s just taken on a life of its own.”

National Legal Director and the Kentucky State Director for American Atheists are other mantles Kagin wears, and he advocates for secular legal causes in Greater Cincinnati. He recently represented a local atheist father in an attempt to prevent his ex-wife from keeping their son in a Catholic high school.

Although the couple shares joint-custody of the child, the court ruled the mother has sole custody in “the limited purpose of educational decision making.” Kagin appealed and the Kentucky Supreme Court might hear the case.

For his many contributions to the national atheist movement, Kagin was awarded the “Atheist of the Year” award in 2005 and 2008 by American Atheists.

Straddling the same era

Lyz Lidell and the SSA knew beforehand about the Creation Museum’s take on science, history and religion. She hoped to find some common thread between her own beliefs and that of the museum’s proprietors. But certain historical, scientific and philosophical discrepancies prevented her and others from taking the museum seriously.

Among other things, the museum stipulates fossils of similar animals are found all over the world because during the Great Flood, animals floated around on rafts, settling on differing continents. Sections of the Grand Canyon were carved out sometime between an hour and four years. Dinosaurs can be no more than 4,300 years old because that’s how old they believe the planet to be. This sets the stage for the most controversial claim: Humans and dinosaurs straddled the same era.

Lidell believes the museum gives patrons the wrong impression. “If you’re trying to misinform people about they way the world is functioning now, you’re going to set up a lot of people to make very bad decisions,” she says.

Contributing to the event’s large turnout was the presence of P.Z. Myers, associate professor of biology at the University of Minnesota at Morris and prominent atheist blogger. His blog, Pharyngula.org, is a sensation in the atheist community, drawing roughly a million page views each month. He was also featured in the documentary, Expelled: No Intelligence Allowed.

Myers came to make his own informed decision about the museum. Like Lidell, he was also concerned by factual discrepancies presented there. “This is a great intellectual vacuum,” he says.

Of concern to Myers was the lack of source material throughout the museum for Biblical explanations that differed from scientific fact. “If you talk to a real paleontologist, they’ll be able to explain to you why they think (a fossil) is 100 million years old, why they think it was buried in flood,” he said. “There is no educational value here for your average citizen.”

The Creation Museum gathering is a testament to the local atheist movement’s vitality. The growing organization exerts its solidarity in Cincinnati in many ways.

They have pool parties, potlucks and a weekly podcast, Answers in Atheism, broadcast live each week from Kagin Manor. Like any other group of like-minded people, they gather frequently and often in public.

The Creation Museum staff and the atheists were generally respectful of each other during the visit, according to separate statements from both the museum and the SSA. Alliance members voluntarily signed a waiver guaranteeing good behavior.

One incident did occur: Derek Rodgers, a college student from Nova Scotia, was allegedly asked to leave for disruptive behavior, while a photographer, Larry Brand, was also asked to leave after being warned about filming by security. Rodgers claimed he was intimidated by the staff and asked to leave.

Derek Rodgers (Photo by Ryan McLendon)

The Creation Museum’s co-founder, Mark Looy, denied Rodgers was kicked out and regretted other patrons’ visits were disrupted by atheists’ reaction to some displays. He was, however, complimentary of the SSA.

“Overall, though, given the several disruptions … the day went well,” Looy wrote in an e-mail.

Lidell was equally complimentary, saying the Creation Museum staff was “very professional, regardless of our worldview.”

Many might view the atheist intervention at the Creation Museum in a negative light or as one group forcing its beliefs onto another. Not so. These functions do the same for local atheists groups as Camp Quest does for children: It creates a sense of community, something every person needs.

People of faith go to a church, a synagogue or a mosque; sometimes atheists go to Creation Museums.