O

hio Rep. Janine Boyd says the danger of guns in a domestic violence situation has touched her personally.

“Domestic violence is a part of so many lives. I know a few friends personally who survived relationships that were violent,” says Boyd, a Democrat from Cleveland Heights. “And I have a very close friend, a young lady I used to babysit, who was murdered by her boyfriend. She was shot and killed after they broke up.”

Boyd asked fellow Rep. Nickie Antonio, a Democrat from nearby Lakewood, if she could be a co-sponsor on Antonio’s proposed law to impose additional firearms restrictions on those involved in domestic disputes.

HB 494, which was introduced by the two representatives last month, would allow Ohio judges the discretion to confiscate firearms when issuing temporary retraining orders for domestic violence. Judges would also be able to decide how long to keep the gun from the accused individual.

“What we’re trying to do is really address that time period initially when a woman files a protection order,” Antonio says. “It’s the time when we’ve seen women murdered by intimate partners with guns or other weapons.”

Ohio’s HB 494 would also create a state law that mirrors a federal law prohibiting those convicted of misdemeanor domestic violence charges of owning or purchasing firearms. States often overlap federal laws to give local law enforcement specific state laws to enforce rather than involving federal statutes. Antonio says passing HB 494 would create a stronger framework for local law enforcement — which responds to the majority of domestic disputes — to follow.

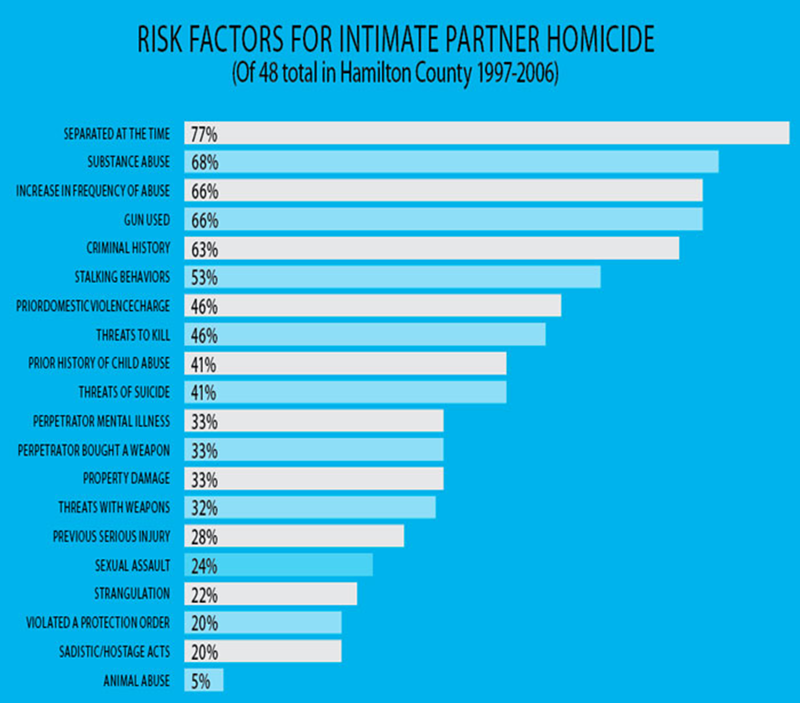

Academic researchers have looked into the existence of guns during domestic-violence-related deaths. A 2006 University of Cincinnati study found guns and breakups were some of the top factors that predict when a domestic dispute will turn deadly. It looked at 48 cases of intimate partner homicides in Hamilton County from the previous 10 years and found that in 77 percent of fatal incidents, the couple was separated at the time. A gun was used 66 percent of the time.

If the bill passes, Ohio will join 28 other states that have similar state laws giving judges the discretion to confiscate firearms when issuing protection orders.

There is research to suggest that such restrictions help reduce the number of homicides from domestic disputes. A 2010 study in the journal Injury Prevention found laws that restrict firearm access for those issued restraining orders results in a 25 percent reduction in firearm homicides.

Domestic violence legislation is one area in which gun control supporters and gun rights activists have often found common ground, says Robin Lloyd, state legislative director for Americans for Responsible Solutions, a gun control group.

“They don’t go after them the way that they go after other types of firearm legislation,” Lloyd says of gun rights activists in general. “I think that, ultimately, this is domestic violence legislation that has firearm provisions.”

But the National Rifle Association still plays a big part in advocating against restricting gun ownership, even in these cases. Dean Rieck, executive director of the Buckeye Firearms Association, a local grassroots gun rights organization affiliated with the NRA, says he is concerned the proposed law is too broad.

Rieck says it could allow a judge to confiscate firearms before that person is actually convicted of domestic violence charges.

“These protection orders are issued just because somebody’s upset or just in case, so there’s not necessarily a proven incident of violence,” Rieck says. “And so, if you’re going to have someone’s firearms taken away and violate a constitutional right, that just seems like the bar’s really low for that.”

On the other side, advocates for further limiting guns say even a brief turnaround between the issuing of a protection order and the restriction of gun ownership can put victims in danger.

Kristin Shrimplin Smith is the executive director of Women Helping Women, a local nonprofit that addresses gender-based violence. She supports HB 494 but worries it won’t cover the critical period directly after an incident when most homicides occur. Police file the motion for a temporary protection order, but a judge has the power to actually grant that order, a process that can take up to 24 hours.

“Of course we’re supportive of any law or policy or procedure or accountability of systems that removes firearms that kill women and children, because that’s the reality,” Smith says. “I would like to see that even quicker than 24 hours, but apparently that’s what’s being proposed. And it’s better than what we have now.”

In Ohio’s Republican-dominated House, firearms provisions have historically been defeated.

Antonio’s previous attempt, last session, to strengthen firearms protections for domestic violence never made it out of the Ohio House’s judiciary committee. Antonio co-sponsored a similar bill with former Rep. Robert Hagan, a Democrat from Youngstown.

In January, every House member voted in favor of a bill that would remove domestic violence victims’ information from public databases to better protect them from their abusers. But the same legislative body also passed a controversial bill last November allowing Ohioans with concealed carry licenses to bring guns inside daycares and certain parts of airports and police stations. The vote was 68-29, almost directly across party lines.

In 2014, 2,165 domestic violence charges were filed by police departments in Hamilton County, according to an annual domestic violence report by the Ohio Bureau of Criminal Identification and Investigation. The Cincinnati Police Department accounted for 1,317 of those charges.

Hamilton County law enforcement agencies reported 1,343 injuries from domestic violence, though none were fatal. Only 10 fatalities were reported across Ohio. The report does not specify the weapon used.

Ellen Newman, the Hamilton County volunteer coordinator for Women Helping Women, says there’s another domestic violence issue the proposed law can’t address; many domestic violence cases don’t make it through the legal system.

Charges are often dropped when victims don’t show up to testify against their abuser in court, Newman says, because victims often fear retaliation or facing the abuser’s family members. Sometimes they find it too difficult to testify against someone they love.

“The system is set up where it relies heavily on the survivor being present at court,” Newman says. “But when we’re thinking about what it’s like for a survivor to go to court to face their abuser, it’s really scary. And the courts are sometimes not necessarily set up to make the survivor feel as safe as possible.”

According to the National Coalition Against Domestic Violence, 43 percent of domestic violence incidents in Ohio in 2010 resulted in no charges being filed. This includes temporary protection orders.

HB 494 is still waiting to be assigned to a House committee, where it will have until the end of this year to make it past state House and Senate votes. It then must be signed into law by Gov. John Kasich.

Antonio says, at the very least, she’s hoping the proposal will start more conversations about domestic violence and firearms.

“I think we need to have the conversation,” Antonio says. “The conversation is important because human lives are important, and frankly, they’re the most important thing.” ©