Joe Civitello moves quickly down the long sloping stairs at downtown’s Contemporary Arts Center. It’s after 10 p.m. on a Thursday in early February, and the day’s visitors have long gone home. As the CAC’s installations director, Civitello generally deals with a range of material like wood and drywall. But tonight, he’s checking in on staff strategically positioned throughout the building to ensure no one wanders too close to where a team of artists and technicians will detonate more than 100 explosives embedded in a wall.

“I’ve seen things come and go,” Civitello later told me at the Fausto cafe in the museum’s lobby, “but this was one of the more interesting things I’ve been a part of.”

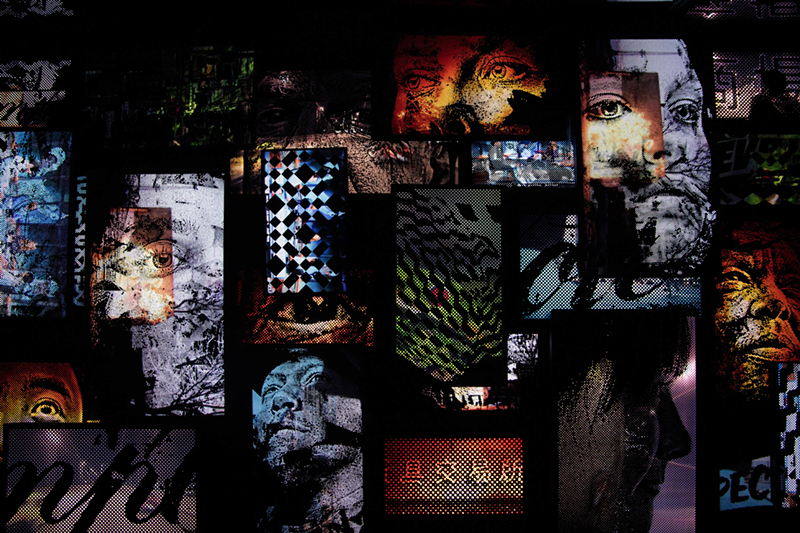

The explosions were conceived by Portuguese street artist Alexandre Farto, better known as Vhils, and filmed in slow motion to create “Identity,” the installation that forms the centerpiece of his current exhibition Haze. Vhils is famous for his use of implements like power drills, acid and explosives to carve monumental portraits on the side of buildings, such as his mural of John Mercer Langston on Over-the-Rhine’s Logan Street. Haze, which runs through July 6, is the artist’s first large-scale exhibition in the United States. This is also the first time he and his team have used explosives inside a museum.

Civitello punches a button on the freight elevator. Building sensors are all operational. Everyone is in their assigned locations. When the elevator closes behind him, it will be taken offline. He listens to the soft crackling of Portuguese from his walkie talkie.

Five floors up, in a makeshift command center in a women’s restroom, Michael Lutz hunches over a pair of computer monitors. A fire marshal looks on as Vhils and his crew adjusts video equipment. From a controller box, wires stretch down a short hallway and around a corner where they connect to more than 100 “air burst” charges.

“It was definitely a different application than what we’re used to,” Lutz later tells me over the phone.

You wouldn’t know from his calm and deliberate manner of speaking that he’s one of the wizards behind the annual Western & Southern WEBN Riverfest fireworks, along with his uncle, Joe Rozzi. They’re part of the Loveland-based Rozzi Fireworks, which was founded in 1895 by Lutz’s great grandfather Paolo Rozzi.

Lutz had arrived several hours early in order to double and triple check each of the charge connections. Growing up around fireworks taught him a healthy respect for their power. Over the preceding weeks, he gathered the necessary permits and coordinated with the Cincinnati Fire Department. He worked with the CAC staff to verify that sprinklers, fire detection and air-handling systems were working, as well as to ensure the blast would present no danger to the building’s structure or the art within. On the night of the blast, he was confident everything would go as planned.

Later, Civitello steps out of the freight elevator onto the fifth floor and watches Vhils’ studio assistants make last-minute adjustments to the camera and lighting. Weighted down with sandbags, safely behind a shield of Plexiglas, the camera points to a wall where, just below view, wires dangle like nodes from a cybernetic porcupine.

It had taken Civitello and his team more than a week to build. They began with a freestanding brick wall half an inch away from the gallery’s real wall. They covered this in layers of plaster-like coating to match the surrounding drywall. Vhils’ studio then used drills and chisels to carve out the word the blast would reveal, and the charges were placed.

Civitello makes his way to the CAC’s Contemplation Room. Here, another group of assistants and museum staff wait with dust masks, goggles and ear protection.

Vhils began incorporating explosives in his work after seeing the devastating effects of the global financial crisis in his home city of Lisbon, Portugal. He had already received international attention for his monumental bas-relief portraits, through which he sought to call attention to the struggles of working people.

“I really try to capture the everyday hero,” Farto later tells me. “We’re humanizing public space, and we’re creating a connection with everyone through the city without needing someone that is iconic or well-known.”

His method of carving into the walls shows how things build over time, unnoticed, like rings in the cross-section of a tree, and how events like a global financial crisis leave their mark on the built environment. The blasts were his response to the economic violence this crisis had made visible.

Civitello adjusts his ear protection and straightens his back against the Contemplation Room’s outer wall. His walkie talkie crackles: “Three… Two… One…”

Fast forward three weeks. Haze is slated to open in just a few hours, and Vhils has agreed to a short interview. My hope is to peel back a layer to show a portrait of Farto, but the soft-spoken 33-year-old encourages me instead to focus on his team’s work and impact.

We walk through the exhibition, starting at the end where faces are carved into weathered freestanding doors. I admire his “Spectrum” series when a peal of thunder billowed through the galleries. Vhils flashes a grin. “We did the explosion. Want to see it?”

“It rattled the walls,” Lutz says later.

It hurled debris across the gallery and jolted tiles in the women’s restroom. Civitello describes how he almost lost his balance as the shockwave ripped through the Contemplation Room’s walls. “You could definitely feel it in your chest,” he says.

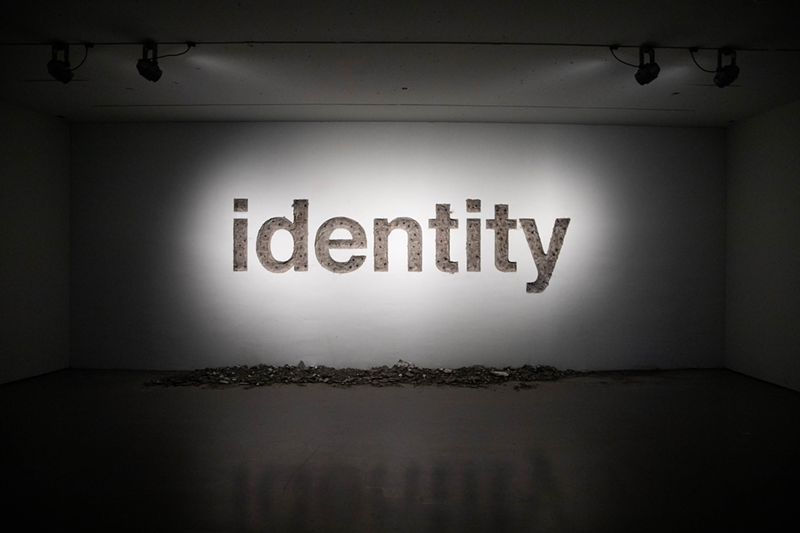

I follow Vhils around a corner to the gallery where the blast had occurred. On the far wall, the word “Identity” looms above a pile of debris. On a screen, the blast replays in extreme slow motion, chunks of brick and plaster floating across the room. Four speakers convey a subsonic rumble. In the clearing dust, what was there all along becomes visible.

“We wanted the museum to be a place where you can go really deep into the concepts of the work,” Vhils said earlier, “and to really challenge the concept of (a) museum.”

What is there within a museum’s white walls that might be revealed with an explosion?

“Art has the power to bring attention,” Vhils told me. “Not just visual attention, but eventually media attention.”

It occurred to me later, while talking with Civitello, and again with Lutz, that here are two of Vhils’ “everyday heroes.” Along with dozens of others who came together on this chilly February night, this blast made them visible.

As the video loops back to the beginning, Vhils strides to an area of the wall that looks like it had been hit with a shotgun blast. Grazing his fingers along the damaged surface, Alexandre Farto’s eyes twinkle in the video’s light.

Haze runs through July 6 at the Contemporary Arts Center (44 E. Sixth St., Downtown), despite its current closure. More info: cincycac.org.