I am most charmed by what I call “little movies,” film projects that feel like the makers channel them from beyond, compelled by something better than money — the fiery need to tell an intimate, heartfelt story. Movies like Dogfight, Gas, Food, Lodging and Tangerine, to name a few. Tiny budgets are key, since the restrictions plus vision inspire real creativity rather than focus group reads. Often, these films feel like they were made in your backyard. And, sometimes, as is the case of the Ethan and Maya Hawke vehicle Wildcat, they really are.

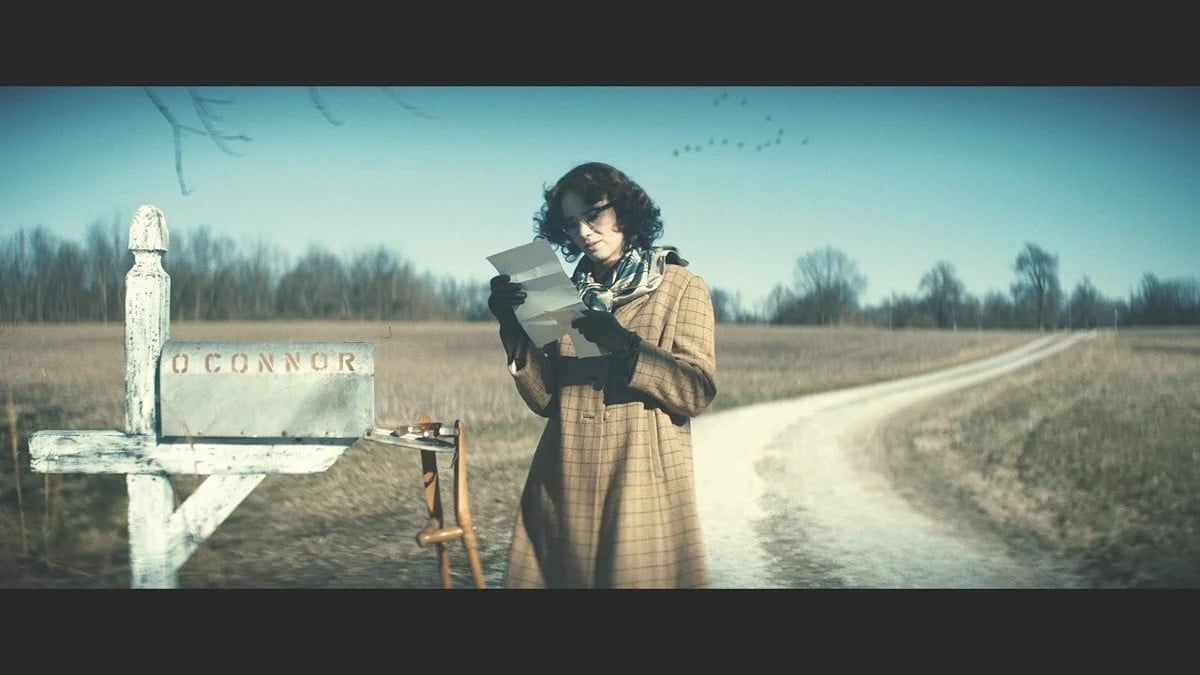

Filmed in and around Louisville, Shelbyville, Frankfort and Loretto, Ky., Wildcat is an odd, lovely and funny glimpse at the life and work of Southern gothic writer Flannery O’Connor. Less a straight biopic, Wildcat is a meditation of sorts on the early career of O’Connor and her transition from Iowa fiction workshop bound twenty-something to the bedridden, peacock-loving genius she would become. Set in 1950, when Flannery is 24 and diagnosed with lupus, the disease that killed her father and will eventually kill her at age 39, the film focuses on Flannery’s life as a writer with huge ambitions, her struggles to come to terms with her serious medical issues and her relationship with her strong-willed, yet loving caretaker mother. The always delicious Laura Linney plays Flannery’s mother, and Maya Hawke transforms from her Stranger Things It Girl persona to the plain, physically ailing and eccentric genius, delivering a nuanced performance. Most importantly to this Kentucky viewer, her accent work is A+ and didn’t grate on me one bit.

Between vignettes of real life, we experience dramatizations of O’Connor’s famous, and often perfect, short stories. These interpretations use the same actors from Flannery’s life to play the wholly original characters she created in her stories, suggesting a connection between O’Connor’s bio and the stories she wrote. O’Connor herself scoffed at the idea that her stories were reminiscent of her life, citing her housebound status as proof. But Wildcat is not interested in explaining away the stories by means of biography, but rather to show that the Catholic O’Connor’s creativity sprang from processing the world around her within the restraints of her illness and station, coupled with her longing to know and serve God.

Traditional biopics create an illusion of telling a whole story of a life, and for that reason, usually fail as art. Their agenda is to create a narrative authority and convince the viewer that what they are seeing is the whole story of a life, or at least, all that matters. What the Hawkes are instead doing with Wildcat is to use her imaginary life as told through her stories, coupled with lines from her letters and, most importantly, dramatizations of O’Connor’s A Prayer Journal to create an interpretation of her inner life. The result is that major themes of O’Connor’s life are only glanced over rather than thoroughly explored, and this can be seen as a weakness. Most galling for modern viewers will be the gentle way O’Connor’s own racism is handled when there is potential for an entire movie that is about nothing but her relationship to race. It is a theme to be grappled with and I would love to see the movie that shows the creators absorbed takes from thinkers like Hilton Als, Alice Walker, and Toni Morrison, all writers who get into the meat of O’Connor and race, and offer complex readings of her work and life.

This longing for an additional movie is not a sign that Wildcat is not a strong work of art though. It is not aiming to be the endpoint of the audience’s relationship with this literary giant, but rather a jumping off point. Like A Prayer Journal itself, an incomplete, strong in craftsmanship, heartfelt pleading with God that inspired Maya Hawke to create Wildcat in the first place, this film is a strong scaffolding for a lifetime of inquiry.

To get maximum enjoyment out of Wildcat, I would suggest reading A Prayer Journal and the short stories featured in the film, preferably before watching the film. Luckily, all these stories are widely available and fun to read! There is also a PBS American Masters doc about FOC that is enjoyable homework.

The Wildcat short story syllabus:

Good Country People

Everything That Rises Must Converge

Revelation

The Life You Save May Be Your Own

The Enduring Chill

Parker’s Back

The Comforts of Home

This story was originally published by CityBeat sister paper Leo Weekly and republished here with permission.