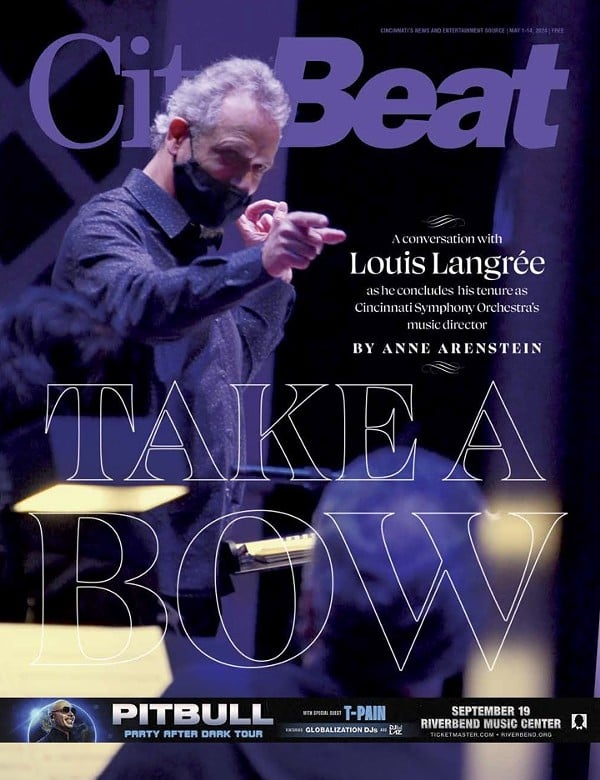

Critic's Pick

The first thought to cross your mind when you enter the Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park’s Thompson Shelterhouse Theatre for David Bar Katz’s The History of Invlunerability, a story about Superman and his comic book creator, might sound like an amusing, nostalgic show.

Comic book panels are everywhere you look, and I do mean everywhere: The walls of the theater are covered with black-and-white images reminiscent of pulp publications from the middle of the 20th century, and even the floor of the relatively bare stage is washed with projections of the same. The walls to the left and right of the stage and to the left and right of the audience section directly in front of the stage contain panels on which changing images — black-and-white and color — are projected throughout the show.

The lights come up on Superman. Handsome actor Steve Wilson has that confident "I’m in charge" look you expect from the Man of Steel. As he begins to describe his genealogy, the panels show images of his caring, adoptive earth parents, Jonathan and Martha Kent, and his biological parents on the lost planet of Krypton, Jor-El and Lara. We're drawn into the fantastic, melodramatic world of these characters as well as Clark Kent, Superman’s alter ego, and his co-workers in Metropolis at The Daily Planet, Perry White, Lois Lane and Jimmy Olsen.

Then Superman explains that his “real” parents were Jerry Siegel and Joe Shuster, the comic-book writer and artist who conceived him in the mid-1930s and sold the idea to DC Comics, which first published stories of the superhero in 1938. With that, Siegel steps onstage, enacted by David Deblinger, a bespectacled, nebbishy schmuck who fans of Woody Allen will readily recognize (pictured above with Wilson). In his fretful, adenoidal voice, he challenges much of what Superman has said, and the two of them commence a back-and-forth conversation about parenthood — especially the troubled relationships of fathers and sons — that continues throughout the play, each one advocating a perspective about the true lineage of responsibility.

This isn’t so funny, and it’s clear we’ve stepped into a new realm. In fact, we’re inside Siegel’s anxious head, where the fantastic stories of Superman swirl with moments of Siegel’s own life and tales of Jews at Auschwitz during World War II. Superman’s opening monologue has revealed that many of the famous superheroes of the golden age of comics were the product of young Jews: Stan Lee (who was Stanley Leiber) created Spiderman and teamed with Jack Kirby (born Jacob Kurtzburg) for the Incredible Hulk.

Bar Katz’s play suggests that these young American Jews, a half a world away from the devastation of the Nazis and their death camps, subconsciously tried to overcome a feeling of powerlessness by creating invincible heroes. Siegel led the way with the ultimate, supposedly invulnerable Superman who fought for truth and justice.

[Read my interview with David Bar Katz here.]

Despite his play’s title, Bar Katz’s subject is vulnerability and how we cope with it. Siegel was a little guy who changed the world, creating a cultural phenomenon that’s still central and prevalent, but he was pushed aside by business forces and greed which he spent most of his life struggling to overcome: He and Shuster signed a paycheck for $130 that was interpreted for nearly 40 years as relinquishing their rights to any profits from the Superman franchise.

When the first Superman film was released in the late 1970s, they were offered recognition and a settlement that today still looks like a pittance, and Bar Katz’s script makes it evident that Siegel never truly benefited from his iconic creation. He was a one-hit wonder, advancing several further concepts later in life that were laughably distant from the great myth he launched in the '30s.

But Siegel’s story is more tragic: His debates with Superman reveal feelings of guilt for not being able to do more, for not having the powers needed to make a difference. We follow three generations at Auschwitz: young Joel (Richard Lowenburg), adult Benjamin (Joseph Parks) and elderly Saul (William Parry), who each fantasize about escape from the camp.

Saul’s hope is pinned on religious faith, Benjamin’s on acts of clever audacity. But Joel believes a savior — in the form of Superman, whose tales he reads in tattered comic books — will come to rescue them. The truth is a harsher reality, one that Siegel has a hard time facing, despite his ability to imagine a man who's invulnerable.

Is this a crushing tragedy? Not exactly, because Siegel’s indomitable zeal to overcome obstacles seems invincible — and that’s a human trait Bar Katz’s script offers as a glimmer of hope, a true thread of “invulnerability” in our human DNA. Just as the prisoners at Auschwitz strive to imagine their escape, hoping against hope, that desire for a better world keeps Siegel going.

Michael Evan Haney has directed this production with a cast of 12, very large for a Shelterhouse show. Beyond Deblinger’s nerdy Siegel and Wilson’s steely-eyed Superman, the rest of the cast play multiple roles: comic book executives, cartoon villains, Nazis, greedy publishers, noteworthy playwrights and journalists. Haney keeps all this action swirling like a mad dream, perhaps Siegel’s final thoughts.

David Gallo’s scenic and projection designs (using original artwork by Joe Staton) are a sight to behold, the perfect visual compliment to Bar Katz’s words. Thomas C. Hase’s introspective lighting design fluidly and dramatically moves the action from one scene to the next.

Publicity for this show carries a warning about material “suitable for adult audiences only.” There is violence that’s hard to watch, bits of bad language and some references to sex, but The History of Invulnerability is more than merely “suitable.” In my book, Bar Katz has X-ray vision to see into the human soul, and his powerful play should be required viewing.

THE HISTORY OF INVULNERABILITY, presented by Cincinnati Playhouse in the Park, continues through May 2. Buy tickets, check out performance times and get venue details here.

Rick Pender's interview with David Bar Katz is here.