Just 18 days into 2017, the Thompsons were Cincinnati’s 21st and 22nd shootings of the year. Alexandrea was the city’s fifth gun-violence fatality. The city had seen 11 shootings and four fatalities by that point the year before, and just 10 shootings and one fatality by that date in 2015.

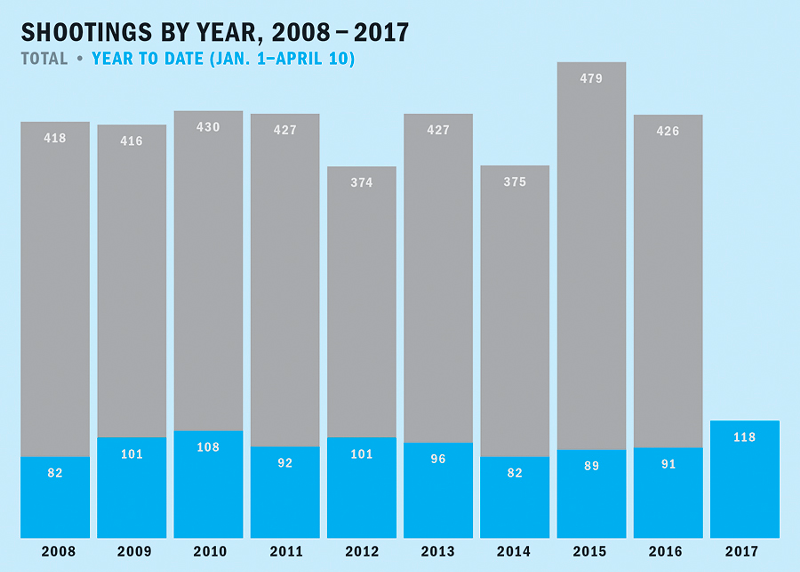

That spike has continued. As of April 10, 118 people had been shot in Cincinnati this year — easily the highest number in the past nine years and much higher than the average of 91 per year during that time period.

With 2017 off to a grim start and the mayoral race looming in November, the spike in the city’s shootings has sparked a political battle and called current efforts at violence prevention into question. Some have pinned the carnage on drugs and petty neighborhood beefs. But others say the problem is systemic — rising from past exposures to violence and inequalities concentrated in predominantly black neighborhoods — and must be treated as such.

Underlining the stakes in the restless search for solutions is the deep sorrow pervading Cincinnati neighborhoods wracked by shootings.

“That spirit, that fight and that love that she had, that tenderness, it’s gone,” explained Freeman McNeal, who lives across the street from the Thompsons, to local media following Alexandrea’s death.

Gun violence in Cincinnati has waxed and waned in individual years but overall has remained steady for about a decade. Last year, 426 people were shot in Cincinnati — just above the past decade’s average of 421.

Part of this year’s swell comes from the March 26 Cameo Nightclub shootout, which killed two and injured 17. While the gun battle in the crowded East End club drew national attention and renewed pledges to address violence in the city, that incident alone doesn’t account for this year’s big numbers.

Law enforcement officials and Hamilton County Prosecutor Joe Deters are quick to blame the violence on shifting battles over drug turf, social media arguments turned into shootouts or both.

“I can’t understand this behavior at all,” Deters said at a news conference earlier this month about the Cameo shootings. “Cincinnati’s a very safe place if you don’t hang around with people who traffic in drugs. Cameo had a lot of people in there who were not good people and who were dealing in drugs, who had multiple convictions for dealing in drugs.”

But those explanations draw ire from racial justice advocates, who say they pathologize predominantly black communities.

“You can’t blame the black community for what has happened,” said Black Lives Matter Cincinnati organizer Mona Jenkins at an April 8 discussion about the Cameo shootings. “You have to own up to the systemic issues that have caused this.”

Jenkins and other activists argue that much of the gun violence is caused by a lack of opportunities for education, employment, political participation, arts and recreation, along with other inequities, especially in Cincinnati’s black neighborhoods.

Gun violence has hit the city’s black communities hardest. Of the shooting victims so far this year, 102, or 87 percent, have been black, as have many of the suspects in those shootings. That’s similar to past years in a city that is 46 percent black and where nine of the 10 lowest-income neighborhoods are predominantly black.

The vast majority of the shootings have happened in those low-income areas of the city, which have seen little investment and few job opportunities. Avondale is 91 percent black with a median household income of just $18,000 a year, according to Census data, and saw 37 shootings last year. The West End, which is 90 percent black with a median household income of less than $13,000 a year, saw 34. The list goes on — altogether, a small number of neighborhoods that are predominantly low-income and predominantly black saw about 65 percent of the city’s shootings last year.

Mount Auburn, where the Thompsons were shot, is one of those neighborhoods. It has already seen a total of four shootings this year, two of them fatal.

While groups like Black Lives Matter view the problem from a radical, system-changing frame, they’re not the only ones who have acknowledged that poverty and disparities in neighborhood violence are linked.

“There is a strong correlation between homicide and income inequality,” UCLA social welfare professor Mark Kaplan told a crowd at a Jan. 26 presentation at the university about research around firearm-related deaths in the U.S.

Kaplan, who has conducted extensive research on the intersections of violence, race and economics, highlighted that counties in the United States with the least inequality also have the fewest gun murders.

Because of a history of racial and economic disparities in the U.S., those dynamics fall hardest on black men. Young African American males have a gun murder rate of 89 per 100,000 — similar to rates in countries with some of the highest murder rates in the world.

And even Federal Bureau of Investigation officials, not known for their affinity toward radical social change, have acknowledged the link between inequity and crime.

“So many young men of color become part of (the justice system) because so many minority families and communities are struggling,” FBI Director James Comey said in a 2015 speech on race and law enforcement at Georgetown University. “They lack all sorts of opportunities that most of us take for granted.”

Eliminating socioeconomic disparities is a huge task in itself. In the meantime, continuing violence in Cincinnati has become a major point of contention in this year’s mayoral election.

Days after the Cameo shooting, Councilwoman Yvette Simpson, who is challenging Mayor John Cranley in the mayoral primary, called a news conference to roll out a three-pronged plan for preventing violence.

Those plans include first responders trained to treat psychological trauma at crime scenes, expanded treatment services for those exposed to violence, providing more opportunities for youth in low-income areas of the city and other public health-based approaches to crime reduction.

“To have a real impact on crime, we must do things differently,” Simpson said at the March 30 news conference in Mount Auburn. “We must address the root causes of violence.”

Mayoral candidate and former University of Cincinnati Board Chair Rob Richardson Jr. released a statement the same day as Simpson’s news conference outlining his safety proposals. They included increased security requirements, like live security cameras for clubs with liquor licenses and histories of violence; boosting the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence; strengthening witness protection program CCROW; and other initiatives, including one that would strengthen jobs programs for those returning from prison.

“That’s the surest way to give them a stake in their community, money in their pockets, and a reason to stay out of a life of crime,” Richardson said in a statement about his policy proposals.

Not to be outdone, Cranley held his own news conference the same day as Simpson’s. He criticized his opponent for relying only on a “soft approach” to crime and touted the city’s partnership with county and federal authorities to arrest gun offenders. He also highlighted his efforts to boost the number of police in Cincinnati.

“Our strategy to reduce violence is a blend of smart community oriented policing and developing holistically our City’s children to have greater skills to resolve conflict without resorting to gun violence and greater skills to pursue careers to provide for their families — a blended approach that is both hard and soft,” Cranley said in an e-mail statement.

Cranley also says the city is working to roll out a program called ShotSpotter, technology which picks up the sound of gunfire and alerts police immediately.

The mayor has made safety a keystone issue of his reelection campaign, but some of his moves in that arena have been controversial.

In November 2015, the Cranley administration, led by City Manager Harry Black, oversaw the ouster of Cincinnati Police Chief Jeffrey Blackwell. A spike in gun violence played a role in Blackwell’s ouster, though Black and Cranley have said that low department morale and accusations of misconduct also led to his firing.

That year, the city saw 479 shootings — a big spike from the city’s average. The next year, under new CPD Chief Eliot Isaac, shootings dropped to 426. But they’re on pace this year to go higher again.

On the campaign trail, Cranley has pointed out that CPD has added about 100 new officers to the force during his tenure. But simply increasing the number of police doesn’t necessarily reduce crime, some experts say.

“Last fall we published a study synthesizing all of the studies of police force size and crime and could not find a scintilla of evidence that expanding a police force would reduce crime,” says John Eck, a University of Cincinnati criminal justice professor. That study looked at both crime data and police department size data from 1968 to 2013 and found no correlation between the two.

For Eck, the key is changes in strategy, not changes in size.

CPD has made efforts to change its approach under Cranley. Last year, the department rolled out a new initiative called Place-Based Investigations of Violent Offender Territories, or PIVOT.

PIVOT is designed to further efforts like the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence, or CIRV, which started in 2007. PIVOT combines CIRV’s focus on the networks linking offenders and the community with data-driven, intensive attention to chronic crime locations.

Even some police reform advocates who have decried racial disparities in policing have applauded PIVOT as a possible way to reduce those disparities while chipping away at neighborhood violence.

Cincinnati Civil Rights attorney Al Gerhardstein, who was instrumental in the city’s 2001 Collaborative Agreement, last year told CityBeat he is hopeful about PIVOT.

The key to the new approach, Gerhardstein said, is engaging community stakeholders, including landlords, nearby businesses, neighborhood residents and others, and by changing environmental conditions such as lighting and traffic patterns that make locations more conducive to crime.

It’s too soon to tell how well that approach will work, Eck says.

“Like most programs that are reasonable, rigor in implementation and sustaining them is important,” he says. “They usually wither once their champions move on — existing in name only.”

Ideas like Simpson’s public health-based approach face a similar problem.

“There is a statistical link between trauma and violence,” Eck says. But he cautions that such programs would have to be implemented and run consistently for a good deal of time before any conclusions could be reached about how well they curb violence. Other cities, including Baltimore and Oakland, Calif. have begun those programs, but only recently.

“Dealing with trauma has great value to those suffering from it, and their loved ones,” Eck says. “That’s no small deal. But this does not mean it will reduce violence.”

What does work? Eck mentions CIRV, which brings together community groups, social service agencies, law enforcement and other organizations in a multi-faceted approach that utilizes community engagement efforts.

The program saw success during its first years, but is “a shadow of its former self” today, Eck says.

CIRV has seen budget fluctuations and leadership departures. The organization started with $600,000 in funding before dropping to just $190,000 in 2011. It has since climbed again, receiving $590,000 from the city in 2015 and $759,000 in 2016.

Despite increases in funding over the past few years to initiatives like CIRV and the adoption of new methods like PIVOT, shootings continue in Cincinnati.

To some, that’s a sign a more systemic approach removing racial and economic inequities is necessary.

“You can approach this problem as a criminal justice problem,” Kaplan said during his Jan 26 talk, “or approach it as a public health or social welfare or social justice problem, and that’s what's missing in the discussion.”

Local activists agree.

“We do know that there’s crime in our community, and this is something we should address,” Black Lives Matter Cincinnati’s Ashley Harrington said at the group's event about the Cameo shooting. “But why? The most oppressed in our society face the most alienation from political power, from society. What does that do to people and communities?” ©