Every couple years, a swarm rolls through Cincinnati, knocking on doors, descending on community council meetings and sweeping through church festivals from Mount Adams to Carthage to shake hands and nurse beers in plastic cups.

Yes, it’s that time again: The race for City Council has returned.

Thanks to a change in 2013 that doubled council members’ two-year terms, it’s been four years since Cincinnati last saw the swarm. But it’s here — and with more than 40 people petitioning to get on the November ballot and out interviewing for the job, it’s as big as it’s ever been.

With the crowded field and a number of returning incumbents, first-time candidates are realizing they’ll need more than a party endorsement or a good fundraising haul to grab a seat. From bartending, brew tours and kickball to whirlwind tours of Cincinnati’s far-flung neighborhoods, candidates are getting creative as they make their cases to voters.

Some of the swarm are familiar names — incumbent Democrats P.G. Sittenfeld, Wendell Young, David Mann and Chris Seelbach are all in the mix vying for re-election, as are independent Christopher Smitherman and Republican Amy Murray. Most of them are doing well in fundraising and protecting relatively safe seats — though there could be some surprises.

There are opportunities for a first-timer, especially one with an endorsement and some fundraising prowess. Councilwoman Yvette Simpson won’t run for re-election because she’s busy running for mayor — the charter won’t let a candidate run for both. Charterite Kevin Flynn is bowing out of political life after his single council term. And Republican Charlie Winburn is term-limited after completing his third term on council.

That means new candidates must vie for three empty seats vacated by council members from across the ideological spectrum or try to topple an incumbent.

So, how to stand out? Here’s how some first-time candidates with key endorsements from local parties are making their pitch.

From playing kickball to leveling the playing field

If you happened by Fairview Park a few Saturdays ago, you might have seen Democrat council candidate Tamaya Dennard campaigning — though it probably didn’t look like a political event you’ve seen before.

Dennard and a couple dozen supporters, volunteers and curious onlookers were engaged in a high-stakes game of kickball in the midday sun. Dennard, who has a tenacious competitive streak, was putting everything she had into the game.

“We’re trying to change what political events are a little bit,” she said as she waited her turn to kick. “A lot of them can feel a little dressed up and stuffy. There’s no fundraiser today, no stump speech. We’re just out here to meet people.”

The crew included Dennard’s campaign manager Kevin Tighe — who helped lead Hamilton County Commissioner Denise Driehaus’ recent electoral win — and a number of supporters in red “Tamaya for Cincinnati” T-shirts. Local comedians provided commentary about the game, occasionally making light of a CityBeat reporter’s drifter-like appearance as he lingered awkwardly near the sidelines.

Shawn Braley organized the event. He isn’t formally associated with Dennard campaign but met her at a Cincy Stories event. Braley co-founded the citywide storytelling project, and after hearing Dennard’s speak about her life experiences, he says he felt drawn to support her campaign.

“I like her authenticity,” he said when asked what sparked his desire to host the kickball event. “She really cares about helping people and about fairness.”

Dennard was raised by a single mother in a low-income household in College Hill. After she graduated from Aiken High School and the University of Cincinnati, she got her start at Duke Energy before joining Councilman Sittenfeld’s office and subsequently working on his 2015 campaign for U.S. Senate. Now, she lives in Camp Washington and works at Design Impact, a downtown nonprofit that works to build inclusivity and address complex social issues.

Her background and her current work touch the core of what Dennard is running on: finding ways to bridge the gap between what she calls “two Cincinnatis” divided along socio-economic lines. One-third of the city lives below the poverty line, including half of the city’s black residents. Addressing the issues that arise from that poverty and racial division will take new perspectives, Dennard says.

“As we see more and more, there’s a lack of understanding between the two,” she says. “There are people who are on Council now who don’t understand the everyday things people are grappling with in the city.”

To that end, Dennard’s vision for her time on Council revolves around policies she believes could help increase equity in Cincinnati. She wants the city to work harder to address neighborhoods without access to grocery stores and to put more money into its struggling Metro bus system, human services budget and initiatives like one that puts psychological professionals on emergency first-responder teams. She says she’ll push to have City Hall reassess the way it doles out tax incentives to developers, especially those who don’t build affordable housing.

“We give too much money away in tax abatements,” she says. “They’re a great tool to draw people to the city. But there are certain communities where they’ve hit their tipping point. I’d like to see us weight them. You have to tell some developers you can’t just make lots of money on these neighborhoods. There needs to be mixed-income housing.”

She’d also like to make the inner workings of City Hall more accessible by holding at least one Council meeting in each of the city’s 52 neighborhoods over the coming four years.

Dennard’s perspective and focus on equity can sometimes put her at odds with her party, she says.

“The barometer for being progressive has been the streetcar,” she says. “The barometer is whether you’re opposed to the demolition of the Dennison Hotel. Of course I want to preserve history, but it’s hard to explain that focus to the people in North Fairmount or South Fairmount who don’t have access to a grocery store and have to be on the bus for hours a day to get to and from work.”

Dennard has pulled endorsements from both the county Democratic Party and the Charter Committee. And she’s raised the seventh-most money of any candidate in the race, bringing in almost $61,000 — ahead of incumbents Young and Smitherman. She has also drawn devoted supporters like Braley who work to get her name out there.

“We won’t have enough money to go on TV, and I’m OK with that,” Dennard says of her campaign strategy, which includes “wine and postcard” nights and a planned tour of speaking engagements on citizens’ porches. “But we’ve budgeted a strong radio presence and a strong digital campaign. I think the ground game is the key. We’ve been knocking on doors for a few months now. I go myself, with my clipboard. I don’t really talk a whole lot, I just introduce myself and ask what people care about.”

Practicing politics from behind the bar

Democrat Derek Bauman, a former suburban police officer and well-known transit activist who lives in Over-the-Rhine, has decided to tap for his council bid an ancient force known to bring people together: beer. On a recent weeknight, he stood behind the bar at C&D Tavern in Northside, slinging the cold stuff to a packed house of supporters and others curious about his campaign.

“This is kind of an un-campaign, as we like to call it,” Bauman says. “I’m really into meeting people in a one-on-one kind of way.”

As he handed out PBRs and Budweisers, Bauman discussed approaches to addiction treatment and homelessness with a social worker curious about his campaign after seeing his Facebook posts.

Other attendees were also drawn to the C&D event by Bauman’s social media presence. Bauman’s a consistent voice on Facebook political forums, where he’s not shy about sharing his political views. (He also wrote a series of columns for CityBeat in 2016.)

Bauman has been a longtime activist supporting Cincinnati’s streetcar, opposing the recent demolition of downtown’s historic Dennison Hotel and other issues that are hallmarks of progressive-leaning Democrats like Councilman Chris Seelbach, with whom Bauman sometimes holds campaign events and shares a campaign office. They often find themselves opposed to fellow Democrat Mayor John Cranley.

Bauman’s campaign manager Eddie Davenport says informal community events are where the candidate really shines. Davenport helped run Hamilton County Clerk of Courts Aftab Pureval’s victorious underdog campaign last year and says he believes Bauman has a similar gift for engaging voters personally.

“When I met Derek, I knew I wanted to run his campaign,” Davenport says. “When we get this guy out meeting people, it’s just natural.”

Bauman has also booked two brewery tours via bus — one to East Side breweries like Mad Tree and Woodburn Brewery and another for more westward spots like Brink Brewing Co. and West Side Brewing.

The outreach goes beyond beer. Bauman recently brought campaign volunteers to a number of neighborhood clean-up events in Northside, Bond Hill and Price Hill.

“That’s how I’ve approached the campaign,” he says about those efforts. “I didn’t want to just host the typical dry, happy hour fundraisers,” though he notes he’s done some of those as well. Davenport says radio and digital campaign efforts are also well underway.

Bauman has raked in more than $70,000 in campaign contributions, campaign finance records show. Those plus a $20,000 loan he gave to his campaign place him sixth-highest among candidates. He has also scored some organized labor endorsements as well as a nod from the influential Charter Committee.

Bauman grew up in Warrensville Heights in Cleveland. His family had a single car, and while his mother drove to her factory job, his father would take the train into downtown Cleveland to work as a travel agent. The experience molded his lifelong interested in public transportation. He moved south after getting a business degree at the University of Akron and spent more than 20 years as a police officer, most recently in Mason, before a knee injury ended his law enforcement career.

Bauman says his goal on Council would be to help move Cincinnati toward adding 25,000 new residents to the city by 2025, though he acknowledges that’s a very ambitious target. Nearly everything he touts on the campaign trail ties into a vision of Cincinnati as a series of connected neighborhoods with strong business districts and thriving small businesses centered around a strong urban core. His pitches include better transit access, rethinking the way zoning and tax abatements work while providing increased financial support from the city for neighborhood development and supporting historic preservation.

“If we can get to firing on all these cylinders, it just makes for an amazing, vibrant city,” he says.

Democrats like Dennard, Bauman and Charter-endorsed first-timer Henry Frondorf — who launched his campaign with an eye-catching single-day mad dash through all 52 Cincinnati neighborhoods — have the challenge of standing out in a crowded field.

Twenty-five of the 40 or so who requested petitions necessary to appear on the ballot identify as Democrats. The Hamilton County Democratic Party has endorsed nine contenders — including all Council incumbents running for re-election, plus Dennard, Dillingham, Greg Landsman, Pastor Lesley Jones and prominent Avondale community organizer Ozie Davis.

Smaller crowd, big ambition

Republican candidates don’t have the problem of oversaturation. The Hamilton County Republican Party has endorsed just three people for Council thus far: incumbent Murray, high school teacher and self-described “new age Republican” Jeff Pastor and Seth Maney, a real estate agent and developer.

The child of two staunch Republicans who also love cities, Maney grew up in Oakwood, a suburb of Dayton. After moving to Cincinnati in 2013, Maney found he had a front-row seat for OTR’s rapid changes as a developer with Urban Sites and as vice president of the Over-the-Rhine Community Council. He moved on to Clifton and left Urban Sites earlier this year, but he’s looking to parlay his experience and civic engagement into a Council seat.

So far, his campaign has been more conventional — hitting up events like the Northside Fourth of July parade and the Church of the Immaculata’s festival in Mount Adams while throwing fundraisers. But Maney will tell you he’s still an unusual candidate.

“I’m not hyper-partisan, but I am a lifelong Republican,” he says. “I’m also a lifelong gay man, and I care about places of density, which haven’t been places where Republicans have been competitive in my lifetime.”

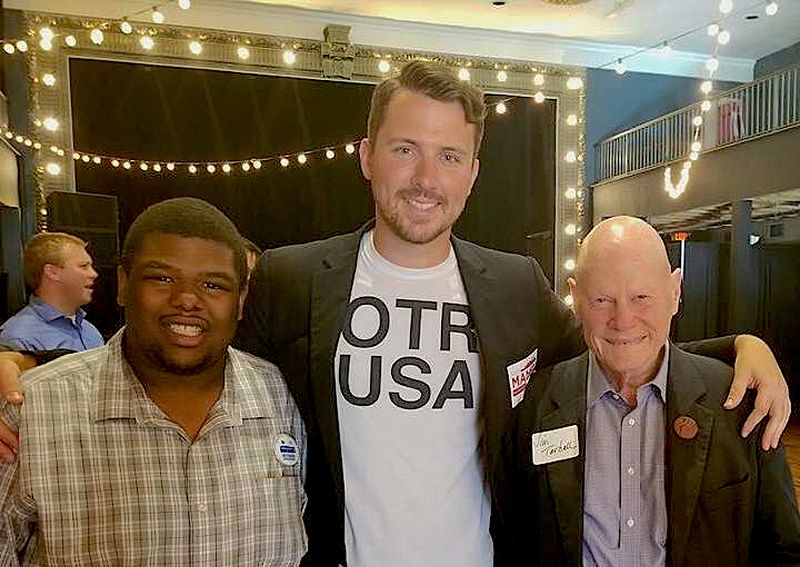

To wit, there are few other rooms in the city where you might find Hamilton County Republican Party Chair Alex Triantafilou, transit activist Cam Hardy and longtime urbanist and former City Councilman Jim Tarbell rubbing elbows, but that was the scene at Maney’s campaign launch at the Woodward Theater in OTR.

Maney says the city could use some Republican representation when it comes to wrangling with the state around increased transit funding — something he supports — and other big issues.

“I think it would do us some good to have some pro-city, pro-transit, pro-growth, urbanist representation from my party,” he says.

Maney jumped into the race earlier this summer and quickly drew attention with controversial statements in The Cincinnati Enquirer aimed at incumbent Councilman Seelbach, Cincinnati’s first openl gay councilmember and an ardent LGBTQ activist. That drew swift rebuke from some in the city’s LGBTQ community, including a sharply worded op-ed from Steve Newsome, who sits on the Human Rights Campaign’s Board of Governors.

Maney has also taken his sometimes-blunt approach directly to City Hall, using a public input session before a Council meeting to chastise council members for missing meetings before pivotal votes.

But he says he’s ready to work with anyone, inside or outside City Hall, on tackling big problems that he sees as obstacles to the city’s growth.

Maney says he sees the city as an ecosystem of connected business districts around the urban core. A self-proclaimed “infrastructure Republican,” he’s quick to talk about the need to reimagine the city’s transit systems and find ways to get more resources to neighborhood business districts.

He also acknowledges the city has an affordable housing problem — one he thinks the market can fix.

“I think it’s a supply problem,” he says of a recent study that found that the Greater Cincinnati has a 40,000-unit gap in affordable housing. “What developers want is consistency, predictability; they want to know how the system works and they want it to work as quickly and responsively as possible. There are different ways that the private sector can help without being forced to do something that isn’t our specialty.”

Like other first-time council candidates, Maney frames himself as an outsider to politics as usual.

“This isn’t the mission of my life,” he says of holding political office. “But it’s an important thing to be an active and assertive citizen. I think everyone will be better off if more people get involved and aren’t afraid to call out BS when you see it — in your own party or not.”

Second Acts

First-timers like Maney, Dennard and Bauman aren’t just contending with incumbents and each other.

There are also returning candidates who have built their name recognition up over time. Endorsed Democrat Landsman, who narrowly lost a bid in 2013, is leveraging his recent success leading the effort to pass the Preschool Promise levy.He's raised more than $200,000 for his campaign — third-most of any candidate in the race including incumbents.

Progressives Brian Garry and Dillingham, who also ran aggressive campaigns in 2013, are back at it again as well. Dillingham has raised about $21,000 for her bid this time around, campaign finance disclosures show, and also scored a nod from the county Democratic Party.

Democrat Laure Quinlivan had two terms on Council from 2009-2013. After falling short of re-election in 2013 by just 900 votes, she’s now looking for her third and has hauled in almost $50,000 to help her in that effort.

On top of all of those candidates, there could be a few more surprises before the Aug. 24 filing deadline. Stay tuned — the swarm is just starting to intensify ahead of November elections. ©