“Art house” traditionally has been a term used in the movie business to connote the type of theaters, usually small and urban, that favor indie and foreign films over Hollywood fare.

But Mark de Jong, a trained artist as well as a renovator/reimaginer of old houses, has a different — and far more literal — meaning for the term. It is a house whose restoration/alteration is done to turn it into, first and foremost, an overall work of art. How people live in it — even whether people live in it — is of secondary concern.

De Jong has previously done commercial renovations, and even took preliminary steps toward creating a full-fledged art house with two earlier projects. But he has been working on the Swing House, as he calls it, for three years now. It is a freestanding 1880s three-story brick building, with a narrow interior width of 15 feet, that is representative of much of Cincinnati’s 19th-century traditional residential architecture. With a blue exterior accented by tin ornamental designs, it fits nicely in the middle of the block-long Avon Place in Camp Washington, a street containing nine homes reasonably similar in size (plus an old warehouse). The street runs between Spring Grove Avenue and an industrial plant.

Neither the location nor the building’s appearance to passersby would lead one to expect that a major new work of Contemporary art, an ambitious and unusual house-size sculptural installation, awaits inside. It is called Swing House because de Jong has removed the interior walls and upper floors and built a swing right in the middle of the opened-up interior. Made from reddish pine he salvaged from third floor joists, the swing is attached by 30 feet of natural-fiber rope to a newly installed metal beam on the ceiling.

The swing is functional in and of itself, yes. But swings are hardly a common inclusion for homes, so this one has far more than a practical use. It represents freedom from architectural convention — it’s a radical departure from our expectations of everyday domesticity. It is, thus, not merely a swing. It is an experiential and experimental artwork — as is the house that surrounds, complements and is named for it.

“Architects use the term ‘program’ a lot,” de Jong says. “In my past projects, I may have included artistic elements, but all the considerations were made around the program of renovating a house. But in this, the program of the house is really the swing… the arc of the swing. All the decisions I made are about the swing.”

Word has slowly seeped out citywide about de Jong’s accomplishment, even if the results haven’t been widely seen. The quietude on de Jong’s part was because he hadn’t finished yet — he carefully plans every detail to have symbolic significance and does most of the work himself. But he has had Thanksgiving-weekend open houses and has welcomed touring groups — including a recent one from Chattanooga, Tenn. CityBeat last year named it “Cincinnati’s Best Architectural Artwork You Probably Haven’t Seen Yet,” and ran a widely republished photograph by staff photographer Hailey Bollinger of de Jong on the swing in the middle of this home. It was breathtaking.

But Swing House is now complete, minus a few exterior touches, and is ready for its first, sustained Cincinnati — and, hopefully, national — close-up. The Contemporary Arts Center on April 20 opens an exhibition devoted to it. It will be on display through Sept. 2. (See sidebar.)

The CAC will display art objects and material derived or inspired by Swing House, plus new work by de Jong. As part of the exhibit, the CAC plans to offer special tours for members during the exhibition, but de Jong will also hold public open houses on his own from noon-4 p.m. April 28, May 5, May 12 and May 19, with possible additional dates added.

“To me, it’s changed the landscape of what art and architecture are in Cincinnati,” CAC Curator Steven Matijcio told CityBeat in April 2017, when he first announced the show. “I’ve not seen a project like this since I’ve been here. I think it’s a major piece that can stand on its own in a national spectrum. I wanted to give it that platform.”

For de Jong, the museum exhibit is validation for Swing House as an art house — and for his years devoted to working toward it. “Because of having a show at the CAC, I feel like I don’t need to defend it,” he says. “You can call it architecture, housecraft, art — of course, it’s all creative. But foremost for me is art. When I was working on this, I was wondering, ‘How am I going to get this known out there?’ It was important for me to have a relationship with the art world. The CAC show has given me an opportunity.”

It’s all the more satisfying because de Jong saved a building in bad shape when he acquired it in 2015, through the city’s nuisance abatement procedure. “I was aware the house had been boarded up by the city, and there was a good chance it could be torn down,” he says. “I didn’t want that to happen.”

But de Jong wasn’t out to obliterate the building’s past by constructing, or deconstructing, something completely new. He wanted to find a way to remind people of Swing House’s past, even while giving it a new future. “I like to say the collaborators are the past tenants, and also the craftspeople that originally built it or were hired to work on it throughout the years,” he says. “I’m interested in the story of the house and preserving it through my lens.”

There is far more to Swing House’s artistic accomplishment than just its swing. There is also all you can see while swinging — or sitting or standing. Among the highlights: In many places on the interior walls, de Jong has removed layers of plaster and paint to reveal older layers, giving all the past colors of its former rooms a chance to visually converse with each other while we watch and “listen.” Light blue still dominates the home’s lower portion, darker blue the higher regions, but there is much variety. He has also used a red-pigmented plaster, signifying warmth, to trace pathways between wall outlets and power switches.

“I kind of see the whole house as being a canvas,” he says.

The wood furniture that de Jong made — sometimes from reused house material, sometimes from other sources — is an extension, rather than an interruption, of his art-house ethos. The pieces are designed to be used, but they also have an illusory quality. The modernist wood kitchen island, which contains a sink and burners, has a base that’s ever so slightly recessed, as if it’s disappearing before our eyes.

The bed, which is toward the back of the house and up against a wooden wall protecting a new metal spiral stairway to the basement, has a mysteriously dark shadow underneath it. Only with great determination can you spot its disguised feet. The three period-accurate wooden cabinets, which are restored and modified, do have feet — but they don’t touch the floor. They appear to be levitating. (They actually are attached to the walls.)

“My reference is the fact that the swing doesn’t touch the ground,” de Jong says. “To the best that I can, I made the furniture look like it floats.”

Ethereally dreamy as the “floating” furniture may be to look at, as if you’re gently hallucinating, it’s the ceiling that is liable to get the most eyeballing. You can see it while you swing. The strong metal beams that de Jong had to install along the sides and roof of Swing House, since the load-bearing floors were removed, serve like a set of Christo’s gates through which one swings. And as you do, if you look up, there’s a white hourglass-like form painted on the otherwise-black ceiling. There are also two sleek, Minimalist-style white ceiling fans that look like 1950s-era atomic clocks.

“I’ve always seen the swing not so much as a vehicle for pleasure as a vehicle for contemplation and the passing of time,” de Jong says. “When you see the hourglass shape on the ceiling, the swing acts as a pendulum and is descriptive of time passing.”

And that gets to the larger meaning of Swing House. “This piece, in its perfect manifestation, is about experiencing,” de Jong says. “It is to really be alone inside the space. A couple or an individual will be having a quiet moment with the house, with my work and with my journey. Being on the swing is about contemplation of lives lived — those who lived in the house as well as that of the person participating in the piece by swinging.”

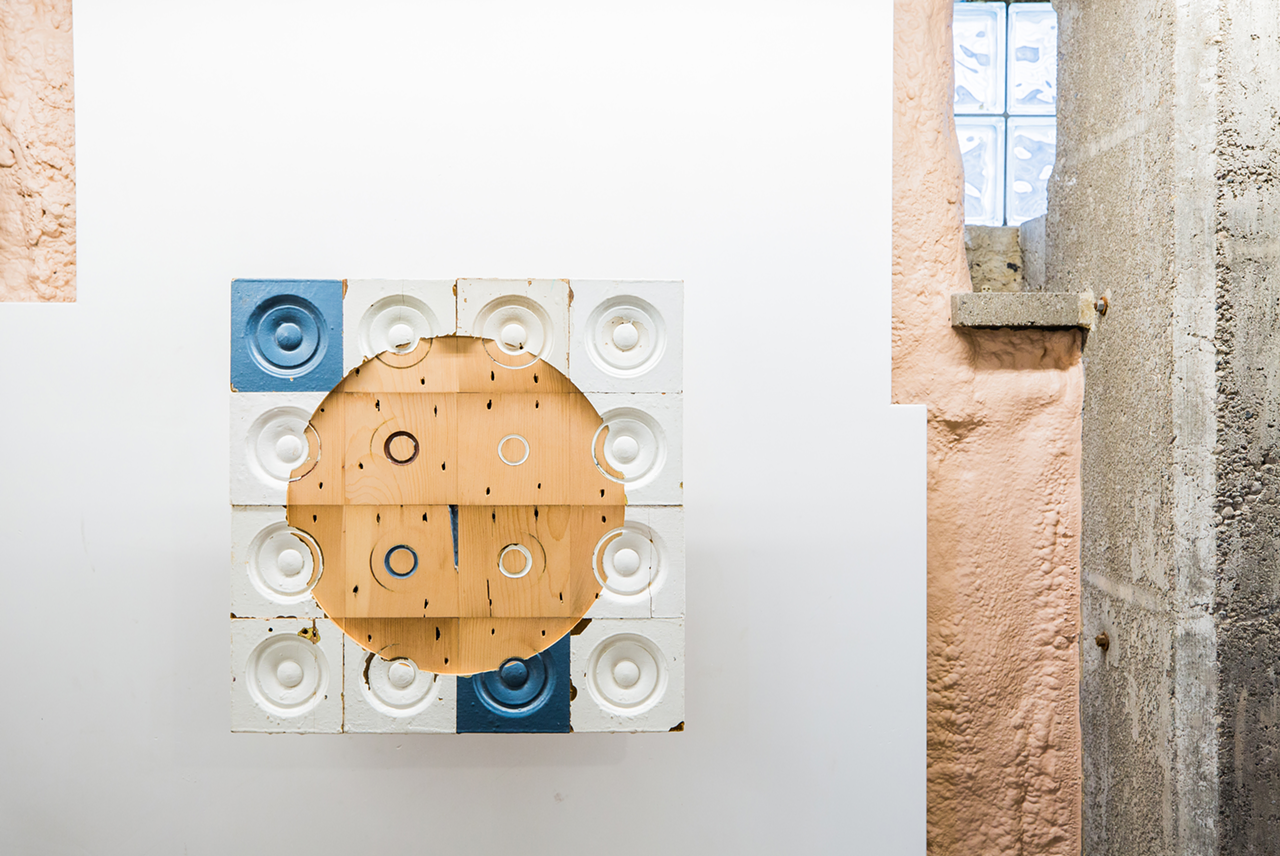

The spiral stairway that twists from the main level to the basement — sort of like descending into water as it passes blue tile walls — leads to a new bathroom and a HVAC system. But de Jong has also turned the basement into a gallery for smaller pieces of art inspired by, and/or reclaimed from, the project. Along one wall is a thin Mobius strip-shaped piece of wood from the third floor — it looks elegant, like a bow tie for a classy building. Protruding on steel armatures from one white wall are circular, multi-colored remnants from the bottom of old paint cans. De Jong found them in the house. He loves to create art out of such things: “That’s something that’s a seduction for me. If there’s evidence of the past, that means there must be a story tied to it.”

Camp Washington is itself a colorful neighborhood, with a strong history as a manufacturing center in addition to its rich supply of older houses. On a recent weekday, the machinery of a gigantic scrap reclamation operation on Spring Grove Avenue clanged away. A trailer-truck with several mangled automobiles waited at its front gate to enter. But the neighborhood has also seen an influx of arts and cultural spaces in recent years — it even has a genuine tourist attraction in the American Sign Museum. Swing House, then, serves as an inspiration for the changes coming to the neighborhood.

“Swing House fits into this idea of people in Camp Washington being really creative, and able to utilize spaces and assets in unconventional ways to make interesting things happen,” says Calcagno Cullen, director of the nonprofit Wave Pool art space on Colerain Avenue. (De Jong serves as its board president.) “It helps to elevate the neighborhood by speaking to Camp Washington’s past and future through its reuse of a house,” she says.

Although born in The Netherlands and raised in North Avondale (his late father Kees was a University of Cincinnati geology professor), de Jong has been making Avon Place in Camp Washington the center of his interests for some time now. His late mother Else purchased a warehouse there in 1980; de Jong owns it now. All told, he owns six buildings on the street and lives in one of them with his affectionate cat, Spinoza.

“She was ceramicist, a potter, and she bought this building back when I was 14,” de Jong says of his mother. “I helped her with it — the first expression of me working on buildings. I lived here for a couple years in the late ’80s, when I was young, and I always loved it. So when I had the opportunity to buy the property, fix up the place and live here, I did that. I thought it would be a short time until I made my next move.”

Before he settled into this locale for good, de Jong first studied to be a fine artist. With hindsight he sees it as valuable, but it was frustrating at the time. After graduating from the School for Creative and Performing Arts, he studied art at the University of Cincinnati but took several years off to travel and live elsewhere. He returned to get enough college credits to transfer to Alfred University in New York State, where he graduated with a BFA degree.

“That experience really helped me have the language I have now,” he says. “That said, when I got done with art school in 1993, I did two shows over a period of years and I didn’t find my fit within the model of a studio-based artist. I did use architectural elements in my work, but my wheels were spinning. So I made a very conscious decision to stop art.”

That was in 1995. Even during his college years, he had worked construction, so he returned to it. He learned painting, plastering, carpentry and specialty finishes. At some point, he segued into buying houses to fix them up and sell.

In 2005, he took possession of his mother’s warehouse, which came with a small house next door. He started renovating another Avon Place home in 2012, which he called Circle House: a precursor to Swing House that uses circles as an architectural element.

“Circles kept popping up — I can’t even say it was a conscious decision on my part in the beginning,” he says. “So I made circles a central theme and added them as art elements in affected spaces.”

That led to Square House in Northside, which also incorporated geometric shapes in an artful way, while still essentially taking the form of a home renovation project. It has since been sold. And he is not standing pat with Swing House — he’s already started work on Stair House, also on Avon Place. “It will be a study in similarities and contrasts with Swing House,” he says.

So what now happens to Swing House as de Jong moves on? He’s unsure. “I would say I’m still open to what it could be,” he says. “I’ve had some thought of it being an Airbnb model. I don’t know what the future is. I just know it’s part of me.”

It’s also now part of all of us.