This story is featured in CityBeat's March 6 print edition.

The Raisins’ self-titled 1983 debut album might have been the quartet’s only official release, but that 11-song, 43-minute effort was just the most obvious touchstone in a legacy that continues to reverberate in the Queen City. Proof surfaced again this month: The Raisins’ prime-era '80s lineup — guitarist/vocalist Rob Fetters, keyboardist/vocalist Ricky Nye, bassist/vocalist Bob Nyswonger and drummer/vocalist Bam Powell — played three sold-out reunion shows at the Woodward Theater March 1-3, a sign not only of the band’s enduring relevance to its hardcore fans but also its members’ ongoing musical devotion and dexterity.

All four have played consistently in one Cincinnati-based project or another since The Raisins disbanded in 1985: Nye as a widely admired blues and boogie-woogie piano player; Powell in various bands, including the ongoing Bucket with Nyswonger; and Fetters in a pair of beloved power-pop outfits that also included Nyswonger (The Bears and psychodots), followed by five stellar solo albums, the most recent being 2023’s Mother.

As you would expect of a band with four different songwriters and personalities, The Raisins’ songs were all over the map, from straight-up rockers and new-wave ditties to R&B-flavored numbers and prog-leaning oddities. The band’s best-known song, the Fetters-penned “Fear Is Never Boring,” was a regional hit, earning heavy rotation on WEBN, whose far-reaching airwaves delivered the song’s provocative opening lyrical salvo to anyone with a radio dial: “Mama’s little baby likes fear and torture — ouch/Mama’s little darling likes violent sex.”

If The Raisins’ dreams of fame and fortune never quite came true — the fact of which no doubt informed the quartet’s unexpected disintegration in 1985 — that lone album did yield a positive review from the Village Voice’s “Dean of American Rock Critics,” Robert Christgau: “These four Adrian Belew-produced Ohioans do their passion proud, with Rob Fetters’ funny but not parodic (or slavish) Springsteen impression on ‘Miserable World’ a typical high point. The songs stick, too, though the lyrics are matter-of-fact enough about bent sex to make me wonder what the really kinky people in Cincinnati are like. Then again, in Cincinnati, a purist mainstream rock band may well define kinky.”

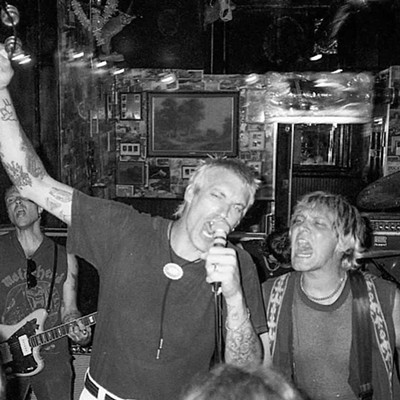

Kinky or not, The Raisins’ biggest asset was their rousing live shows, which drew a rabid following to bars and clubs across the city, long-gone places like Alexander’s, Shipley’s, Crossroads and Cooter’s. Evidence of the band’s stylistic breadth and live acumen is evident on Everything and More, a hard-to-find, self-released compilation of 56 songs they performed between 1980 and 1985. It’s a head-spinning, loose-limbed showcase, a recorded monument to why so many jumped at the chance to witness the band’s recent reunion shows, which was just the fourth time they’ve played together in nearly 40 years.

CityBeat spoke with The Raisins separately by phone in between their reunion rehearsals, each member emitting enthusiasm about the act of playing together again. That’s not to say it was an easy endeavor.

“Everybody’s been very musically active, and that’s a plus because this stuff is pretty demanding,” Nye says. “This would not happen if we weren’t in good musical shape. We’re rehearsing in Bob’s basement. It’s just like we used to work, all in a tight space. A lot of it is like, ‘What the hell were we playing? What was I doing?’ Some of these songs I listen to, and I’m embarrassed. Or, alternately, I’m like, ‘Wow, who was that?’ It’s like visiting a past life or something.”

Perhaps the most daunting aspect of the reunion was revisiting songs that in some cases were written when Jimmy Carter still graced the White House.

“When we wrote those songs, we were serious songwriters and we really cared about the material,” Fetters says. “I don’t think my worldview has changed that much, which is surprising to me. Actually, I think I might be a little more optimistic than I was in my twenties. A song like ‘Miserable World,’ which is on the Raisin album, it’s like an old man singing about the state of the world and the hopelessness, but maybe that goes hand in hand with being 26 years old. We were not starving, but we were pretty damn close to starving back then.”

Powell was the final piece of the classic Raisins lineup — and the last in a long procession of drummers — to lock in place in the fall of 1980.

“The five years I was a Raisin, that was the hardest-working band I have ever been in,” Powell says. “I’ve been playing for over 50 years and been in a lot of bands that were going after it. The Raisins resonated with a certain group of people. They just really appreciated what we were doing. We weren’t a trendy band, and our fans weren’t very trendy people. They were all kind of different, too. A lot of those people are still really good friends with each other. It’s a cool thing, man. The whole scene was.”

All four Raisins contributed to the songwriting process, which means there wasn’t a signature sound or central singer for prospective music-biz types to sell.

“We covered a lot of ground,” Powell says. “That was probably our downfall when the industry looked at us. They were like, ‘What the hell is this? What box do we put this in?’ Clive Davis came to see us, and he said, ‘Who’s the lead singer?’ There really was no single lead singer. He told us we were ‘unfocused.’ And then he went out and immediately signed A Flock of Seagulls, so there you go.”

Yet the fact remains that the foursome’s diverse, ear-wormy songs left a lasting mark on a significant swath of listeners. Is Nyswonger surprised about the continued interest in The Raisins four decades later?

“Yes and no,” he says. “I know there are still a lot of people who say, ‘That was the best band ever.’ That’s very gratifying. I think a lot of people heard us at a time in their lives when they were just kind of figuring things out. They say people stop listening to music after they’re 22, but I guess we had enough people come to see us at that time in their life when it was really something that could profoundly affect them.”

“And the cool thing was that we weren’t just playing the hits of the day, we were playing our own stuff,” Nyswonger continues. “It was like, ‘Are you hip to what these guys are doing?’ We had a bit of a cult. The fact that those people are still alive and willing to buy a ticket? Yeah, I was a little surprised, but the fact of the matter is that we had a great reputation. When the band stopped playing a lot of people were really mad.”

Fetters agrees that the band pricked the right ears at the right time — but he also thinks there might be a more practical reason for the interest in the reunion shows.

“I guess a lot of people grew up with us and we were part of their youth,” Fetters says. “They’re probably looking at us and thinking, ‘Hey, these guys might not be around to do this again.’”