As the City of Cincinnati and Cincinnati Public Schools approach the end of an agreement they struck in 1999 about the way in which the city awards tax abatements, debate has increased about those programs.

Cincinnati City Manager Patrick Duhaney yesterday released a memo saying that, mostly due to a complex state funding formula, the district has gained significant revenue from the city's many tax abatements. Those abatements also helped foster development that might not have happened otherwise, Duhaney wrote, shoring up the city's property tax base and improving the value of surrounding properties.

But CPS representatives have said the abatements have cost the district money, and that the city should rework the way it gives out tax breaks to commercial developers and homeowners. District representatives today countered Duhaney's memo, saying the state funding formula is unpredictable, out of local control and may change significantly soon anyway. They also question the city's data.

Meanwhile, a third party could help the proceedings, the powerful Cincinnati Business Committee said in a letter to board members yesterday. But that's not a great idea, activists critical of the city's abatement policies say.

The 1999 tax abatement agreement arose from the 1996 vote to build Paul Brown Stadium and Great American Ball Park on the riverfront. It allows the city greater power in striking deals with commercial property developers when it comes to tax incentives — hefty discounts on property taxes meant to incentivize new development within the city limits.

Hamilton County Auditor Dusty Rhodes estimates that about 13 percent of the total value of all property in Cincinnati is currently tax exempt due to various abatements.

Those abatements have a potentially large impact on the school district, which receives 45 percent of its money from property tax proceeds, and its ability to educate the roughly 36,000 — and growing — students enrolled at CPS.

Under the agreement between the city and the district, the City of Cincinnati can offer developers of commercial properties (office buildings, retail, industry and any residential development containing more than four units) exemptions on up to the full amount of the appraised value of the improvements — renovations or new construction — that a developer makes to a property for up to 15 years. The city can also offer developers the opportunity to roll the money they would have paid in taxes on renovations or new developments into what are called Tax Increment Financing Districts. TIF money can only be used on improvements immediately within those districts, generally increasing the property values within them.

Without the 1999 agreement, the city could only offer 50 percent abatements and 75 percent contributions to TIFs without the school district’s approval under state law. The city may also be liable for 50 percent of income tax revenue over $1 million a new development generates.

In return for the ability to grant those generous abatements, the city agreed to pay CPS $5 million a year for 20 years for foregone stadium property taxes and to agree to require developers to pay 25 percent of the money they would have paid in taxes — an arrangement called payments in lieu of taxes, or PILOTS — for abatements and 27 percent for TIFs.

Those deals have been the subject of increasing scrutiny — and some rancor from critics across the ideological spectrum — in recent years as some say that the city could use the abatements to incentivize things like affordable housing, higher environmental standards and other asks. Without those extra criteria, abatement skeptics say, developers are too easily let off the hook for taxes they should be paying.

Some, however, including those with the city’s Department of Community and Economic Development, have defended the abatement policies, saying they allow the city to compete with other municipalities wooing developers and also give the city the chance to bridge financial gaps for valuable projects that might not otherwise be feasible.

Duhaney's memo today goes further — stating that the district gained more than $9.3 million in 2018 because of the commercial abatements governed by the agreement and separate residential abatements, which are not governed by the 1999 deal.

That's because the state's funding formula takes property valuation of a district into account, Duhaney argues. When property is abated, CPS stands to gain more money from the state's formula.

"Generally, if the assessed property value in a district increases, then the state's funding to CPS decreases," the memo reads. "The assumption underlying this result is that since the aggregate assessed property value in the district increases, then the school district will be receiving additional local revenue and will require less revenue from the state."

A $1 million tax abatement, the memo claims, nets the district an extra $7,000 despite $11,200 in forgone taxes a year when PILOTs and state funding increases are both considered.

CPS representatives have said negotiations shouldn't depend on state funding, however, because it is unpredictable and is likely to get moreso. Currently, plans are working their way through the Ohio General Assembly to completely rework the state's school funding formula, which the Ohio Supreme Court declared unconstitutional in 1997's DeRolph vs. Ohio.

"In our view, the make-whole calculation does not and should not include state funding," CPS General Counsel Dan Hoying said today during a hearing about the abatement policies. "It can change and has changed and will change again. It's speculative" to assume that state funding will fill in gaps left by abatements, he said.

Further, the formula that determines state funding based on district wealth is dependent on factors outside the district's control, the district says.

"The wealth index calculation is relative to how the state is performing," CPS Treasurer Jennifer Wagner said today. "If another district becomes more poor, we could be seen as relatively richer without anything on our end changing."

Wagner also said that the data the city presents is "dramatically different" from the data delivered to the district by a state expert on school funding.

"The city manager does not provide an explanation in his letter about how the city calculated the impact of state funding," Hoying said.

Last month, district representatives argued that CPS has lost millions from the city's abatement policies.

In 2017, for example, the district says it lost $700,000 in commercial property tax proceeds as the city gave $291 million in commercial abatements and $641 million in TIFs.

That doesn't include another place where CPS says it loses money that isn’t governed by the 1999 agreement — the bevy of residential abatements the city hands out for single-family homeowners or owners of residential buildings with four units or less. According to the district, it lost $5.7 million on residential abatements in 2016, $8.3 million in 2017 and $7.4 million in 2018. The district receives no compensation for those abatements.

The district's negotiation team has recommended a shorter term for the next agreement and wants the rate at which the city reimburses the district for abatements calculated on a yearly basis The district's team also wants CPS to be compensated for its administrative costs when it comes to tracking abatements and wants to be able to approve any extensions of deals between the city and developers.

Talks about a new deal kicked off in June last year with a joint meeting of Cincinnati City Council and Cincinnati Public Schools' board members. After that, both the city and CPS picked teams to explore a new agreement further.

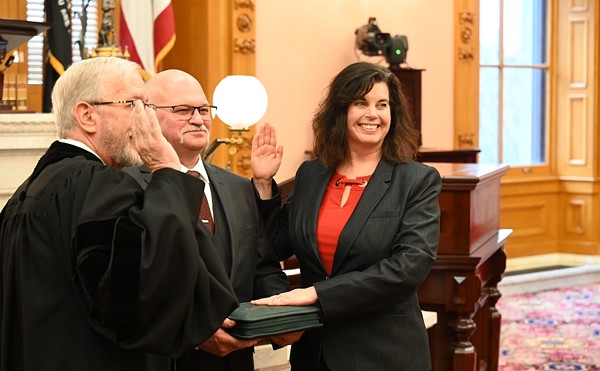

Cincinnati City Solicitor Paula Boggs Muething told Cincinnati City Council in January that those teams had met twice — an assertion CPS board members disputed.

“We have had some very productive discussions,” Muething said then. “I would say that we have met to discuss the framework for a new agreement. I think there is general agreement on the framework and the factors to work through. We have had some very productive and informative discussions.”

But members of the Cincinnati Board of Education pushed back on that days later. Four members of the board said they had no knowledge of any talks about the abatement policies between the city and the school board. The board must give final approval to any agreement, as must Cincinnati City Council.

In his memo yesterday, Duhaney said the city and district had been talking, but that the district ended negotiations.

"The city administration has had discussions with CPS administration to discuss possible terms for a new agreement," Duhaney wrote. "Unfortunately, CPS leadership discontinued those discussions."

In a letter sent to CPS board members yesterday, the Cincinnati Business Committee said it would be willing to engage a third party to help broker a deal. That's something board member Ryan Messer said he would be open to. Messer read the committee's letter aloud at yesterday's hearing. Other board members were more skeptical, however.

“Our organizations — the Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber, the Cincinnati Business Committee and Cincinnati Regional Business Committee — are interested in helping both parties gather and understand the financial impact of the Agreement and are looking to engage a third party to provide assistance,” the letter from Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber CEO Jill Meyer and Cincinnati Business Committee President Gary Lindgren reads.

Board members said they will continue considering the issue before taking action.