At an Aug. 23 press conference, as Hamilton County Prosecutor Joe Deters declared the investigation into the police shooting death of David “Bones” Hebert over, clearing the officers of any wrongdoing, Paul Carmack was waiting outside the room, getting occasional updates from members of the media.

Carmack, charged by Hebert’s family as administrator of his estate and their local representative, was denied access to the event by Deters’ office.

“We were in the building, there to meet with (Deters). We didn’t want to ask questions. All we wanted to do was sit in the back of the press conference and hear what he said,” Carmack says. “They wouldn’t let us in. What happened there, it wasn’t expected. It was about politics. It wasn’t about answers.”

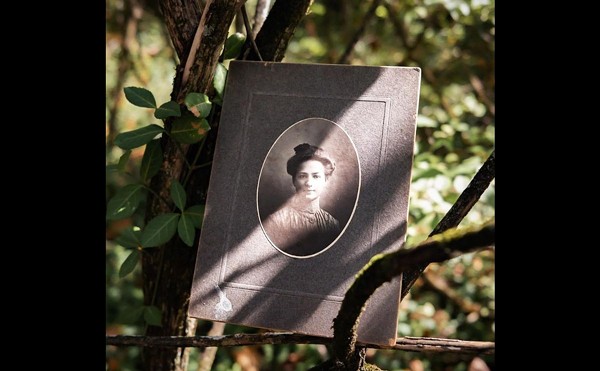

Now, a month after Deters closed the case and five months since Hebert was fatally shot by Cincinnati Police, the well-loved musician’s friends are still looking for answers from Deters, the Cincinnati Police Department and the city’s Citizen Complaint Authority. To them, the case hasn’t been closed at all.

In the early morning hours of April 18, police received a 911 call. The caller told police that Hebert, a 40-year-old cook and musician from New Orleans, attacked him in Northside, stole a sword and stabbed him with it. Police responded and, shortly afterward, found the heavily tattooed and easily identified Hebert walking his dog nearby with a female friend. Police stopped the couple and began questioning them.

While officers questioned Hebert, they say he ignored orders to keep his hands out of his pockets. Then, with one officer standing two feet away, according to police, Hebert went into his pockets once more, pulled a knife and advanced on the officers. Sgt. Andrew Mitchell, a five-year veteran with the department who had arrived on scene midway through the stop, drew his weapon and fired twice. He shot Hebert in the chest — a fatal wound — and upper arm. The knife flew from Hebert’s hand, and he died almost immediately.

After an internal police review, Hebert’s case was eventually turned over to Deters’ office. Months later, the prosecutor cleared the officers, offering his conclusion that “the police officers committed no crime and further were justified in the actions they took.”

Citing toxicology findings, which said Hebert had a blood alcohol content of 0.33 — more than four times Ohio’s legal limit to drive — along with marijuana and psychedelic mushrooms in his system, Deters said Hebert was “blasted,” threatened officers with the knife and posed a clear threat.

Friends of the musician disagree.

Rigel Behrens is one of those who’ve started a website, www.davidboneshebert.com, and a Facebook page to keep Bones’ story from fading away.

“Bones wasn’t a guy who was ever violent or dangerous. He was more likely to hurt himself, being drunk and acting like a dummy, than threaten someone else,” she says. “When I first heard what happened, it didn’t make sense. It still doesn’t.”

“There are still too many inconsistencies, too many questions,” adds Carmack, who has hired a lawyer to conduct an investigation for the family — Hebert’s elderly parents still living in Louisiana and a half-sister who lives in Philadelphia. “There have been inconsistencies in the police’s version of events from day one. Inconsistencies that haven’t been answered to our satisfaction.”

According to Carmack, he and the family’s attorney are still waiting for the city to release paperwork and other evidence, not to mention Hebert’s personal effects, despite the case being closed. When the evidence is finally made available, there are several points the family’s investigation will look into.

Chiefly, they’ll look at the involvement of the officer who shot Hebert, Carmack says.

“I think that’s the main thing that bothers us. Other officers were on the scene before Mitchell, and were handling it. Other officers were standing closer to Bones. Mitchell arrived on scene and within 54 seconds, he had pulled his weapon and shot Bones twice before the other officers had their hands on their guns,” says Carmack. “Clearly, the other officers didn’t feel threatened. I think the judgment of Sgt. Mitchell has to be looked at.”

Carmack notes that Mitchell has been the target of previous complaints about excessive force and another incident when he was accused of inappropriately using a Taser on a teenager in 2008. A civil lawsuit is pending in that matter.

The knife police say Hebert wielded will be another item examined, Carmack adds.

Once shot, according to police, Hebert threw the knife, breaking a nearby window. The knife, according to crime scene photos, landed 25 feet away, blade sticking in the ground. Carmack questions how, once fatally wounded, Hebert could have accomplished the throw.

“I went out there and measured it, and it was more like 35 feet. How does someone who died almost immediately throw something that far, with that much force?” he asks.

Another concern is why police cruiser cameras didn’t record the events.

The only video available from the event starts after the shooting. Video from three separate cruiser cams show only officers removing the dog leash from Hebert’s hand after he had been shot. It does not show the initial stop or the shooting.

“They test the cameras before every shift,” Carmack says. “I’ve seen the video of them testing the systems at the start of their shift, and it was working. How do all three cameras malfunction at the same time? And start working again right after Bones is dead? How does that happen?”

Carmack and the family’s attorneys plan to ask for recordings from the entire evening from the cameras, and may ask to examine the hard drives that store the video to look for signs of tampering.

If there was complete video, CPD’s version of events would be easier to believe, Behrens says.

“For anyone who knew him, it’s hard to accept that Bones was threatening anyone. I don’t think anyone doubts he was (drunk),” she says. “He was probably taking a while to answer questions and it would take him a while to stand up. But I don’t think he could have acted quickly enough to be a threat to anyone. If there were video, and we could see it, it would be easier to accept. Without video, their version of events is just hard to believe.”

Carmack and the family’s attorneys are still petitioning the city for evidence. Once they have it, Carmack says, their investigation could be a lengthy process, taking months. Until then, friends of Hebert will continue to hold events in his memory and keep looking for answers.

“We’re not cop-haters. We’re not,” Carmack says. “We respect that our police officers do a tough and dangerous job. In this case, though, it all comes back to the judgment of one officer and the lack of answers. We’re going to keep asking questions because the public deserves more of an explanation than what we’ve been given.”