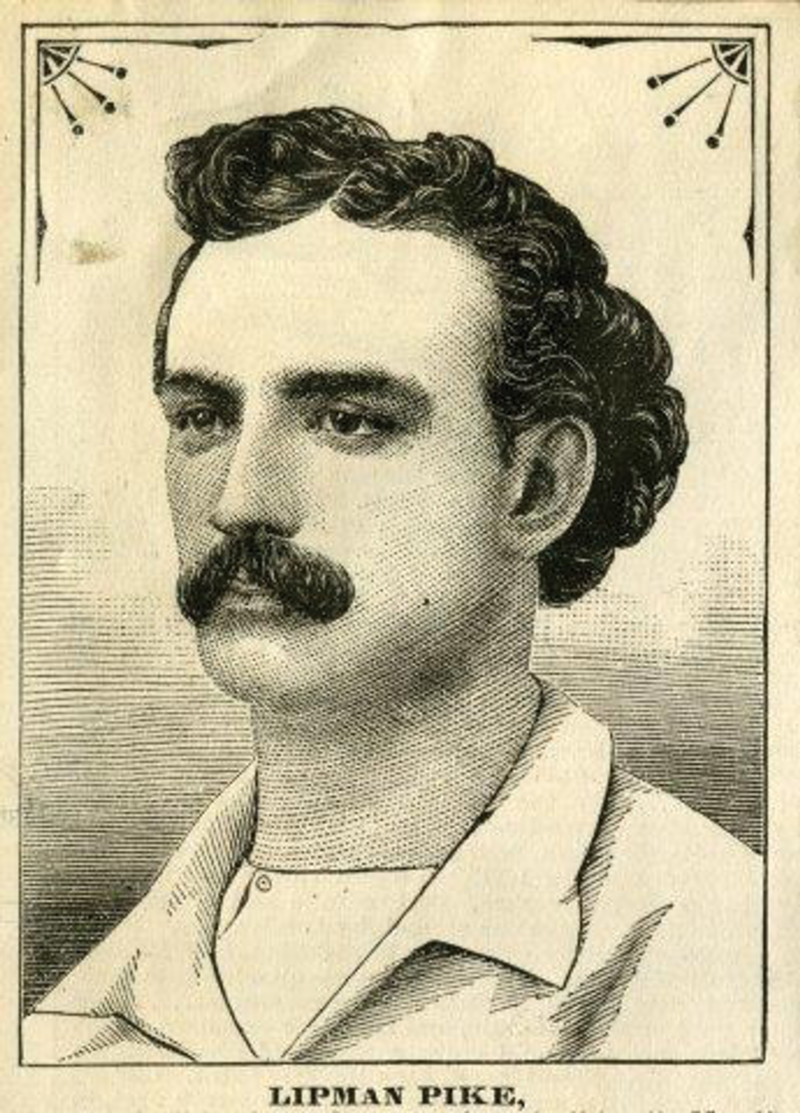

Despite a vagabond baseball career that saw him careening from team to team across the Northeast and Midwest for a decade, Lipman “Lip” Pike arrived in Cincinnati in early 1877 to play for the Red Stockings — the early name of today’s Reds — amid a fair amount of hype.

During that time, when the ball was made differently and therefore less lively than today, Pike was perhaps the game’s first great power hitter, a masher who led various leagues in home runs and accrued enough hardball acumen to be named the Reds’ captain at the start of 1877.

Thus began a brief but hugely influential stay in Cincinnati by the sport’s first home run master. Pike stuck with the Reds only for about a season and a half, but he endeared himself so much to the local fans and his teammates that the Cincinnati papers followed his career even after he left the city in mid-1878.

“While Lip Pike only spent parts of two seasons of his colorful career in Cincinnati, he left a distinctive mark on Reds baseball history,” says Chris Eckes, Reds team historian and museum curator.

Upon Pike’s unexpected death in his hometown of Brooklyn in late 1893, the national magazine Sporting Life published a report from its Cincinnati correspondent burnishing the player’s legacy in the city. “Among the old-timers who followed the fortunes of the Reds ... memories of the days long ago have been stirred up by the announcement of the death of Lipman Pike at his old home — Brooklyn. It was in that city as one of the Atlantics that Lip Pike won his spurs before he was secured to play centre (sic) field for Cincinnati.”

The dispatch asserted that Pike, making the feat look routine, was the first Reds player to crush a home-field, out-of-the-park home run and that, even in his advancing years, he showed his speed by winning a bet that he could out-sprint a younger teammate.

“The roster of ball players who once wore the red and who have been called out by Umpire Death is not very large, but in the passing away of ‘Lip’ Pike, one of the greatest sluggers who ever battled for Cincinnati, has joined the file in eternity.”

But Pike’s vast influence wasn’t limited to the Queen City, and it wasn’t just as the game’s first great power hitter. In addition to those marks he left on the sport, Pike actually was the first professional baseball player, having been paid $20 by the Philadelphia Athletics in 1866.

His impact on baseball didn’t stop there. The son of a Brooklyn haberdasher, Pike was the game’s first Jewish superstar. More than a half-century before the Tigers’ Hank Greenberg blossomed into a hardball legend, Pike was crushing home runs and enjoying a popularity that had heretofore escaped American Jewish athletes.

Burton A. Boxerman, co-author of the two-volume book, Jews and Baseball, says Pike achieved his fame by not only displaying unprecedented power at the plate but also with his blazing speed and craftiness on the basepaths. His defensive abilities, especially in center field, were none too shabby at a time when players didn’t wear gloves or mitts.

“He was the first of many things,” Boxerman says of Pike. “When it comes to the Jewish people, whether it was baseball players or anybody, a number of Jews take pride in someone who was the first to accomplish something. Even with sports, which might on the surface seem trivial, was something Jews took pride in when they were the first in something.”

The stereotype of the lack of Jews in the American pastime goes back decades, if not centuries. In 1903, major league player Barry McCormick was quoted by various publications, including the Cleveland Plain Dealer and Sporting Life, pondering why there weren’t more Jewish ballplayers.

“One thing that puzzles me is why Jews don’t play baseball,” McCormick said. “... Back in the ’70s there was a crack Jewish player, Lipman Pike. ... Somehow or other, the Jew does not play ball. He is athletic enough, and the great number of Jewish boxers shows that he is ... adept at one kind of sport, at least. I see Jewish names in the football elevens and Jewish boys making good in track teams. Jewish gentlemen of means back the ball clubs and are good game backers, too. Yet the athletic Hebrew does not play ball. Why is it?”

Sporting Life placed the clip under the headline, “A Singular Fact.”

Pike’s status as a Jewish trailblazer takes on special significance in May, which is Jewish-American Heritage Month.

Overall, Pike had what Boxerman, with some amount of understatement, calls an “interesting” career and life. On top of all those firsts, Pike — born in 1845 and who enjoyed a playing career that spanned a quarter-century — tried his hand at umpiring after retiring as a player. In 1881, he was infamously among a group of players who were blacklisted by the National League under dubious charges of “general dissipation and insubordination,” according to The New York Times, for supporting players’ rights.

Pike was reinstated by the league a few years later but was undeterred by the regulatory hiccup in his career and apparently continued to be a staunch supporter of players’ rights. In 1890, when fellow player John Ward, who represented dozens of players challenging the National League’s infamous “reserve clause” that dictatorially chained a player to his current team, went to court for the right to bolt to the renegade Players’ League, Pike took a keen interest in the proceedings.

By the time he died suddenly of heart disease in 1893, Pike had garnered a reputation far and wide not only as a talented, heady and influential player but also as a gentleman who represented the best of the game on and off the field.

“The death Tuesday, in Brooklyn, of ‘Lip’ Pike, the veteran centre fielder ... was a shock to his many friends,” stated the Oct. 12, 1893 New York Herald. “He was one of the old time players whose professional life had been an honor to the national game, and who quit the profession without being forgotten.”

Pike’s lasting influence was still felt in 1904, when Sporting Life magazine called him “perhaps the hardest hitter the game ever produced.” As late as 1936, when the National Baseball Hall of Fame elected its inaugural class of inductees, Pike — even though he had played 60 years earlier and died more than 40 years previously — received a vote.

But much of Pike’s reputation was accrued during his season and a half with the Reds in Cincinnati, says Eckes, a fact that makes Pike stand out in franchise history. Especially in 1877, when the Red Stockings were, quite simply, lousy, Pike was often the only bright spot for a team that floundered in last place in the nascent National League — which, ironically enough, given Pike’s later support of the dissident Players’ League, benefitted greatly from Pike’s star power.

Following the disastrous 1877 season, the Reds reorganized and brought on a bunch of new talent that bolstered the team’s fortunes in 1878, when the Stockings were surprisingly competitive, thanks partly to Pike’s knack for timely hitting and smooth fielding.

Still, despite shining for the squad, Pike was released by the Red Stockings in mid-season under still unclear circumstances. Pike didn’t miss a beat, though, and continued his playing career for several more years for several other teams.

In July 1878, shortly after his release by the Reds, Pike was feted by teammates and other admirers in the Queen City, who gave him what the Cincinnati Daily Gazette called “a beautiful gold medal.”

“It consisted of a scroll, bearing Mr. Pike’s name, to which is attached the pin,” the paper read, “from this is suspended two miniature bats crossed, and from this a field with bases and ball. Upon the field is inscribed, ‘Lip Pike, from his friends in Cincinnati.’ ” ©