What was a supernova on the Cincinnati educational scene in the mid-2000s now looks like a flameout.

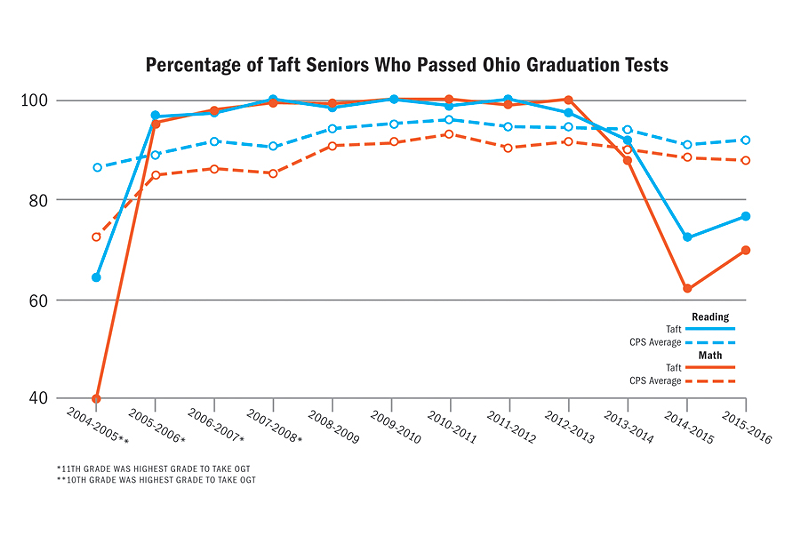

From 2006 to 2014, Robert A. Taft Information Technology High School became a nationally celebrated beacon for urban public schools overcoming poverty and crime. From the bottom of the pack, Taft soared past the city’s other mostly black schools on the Ohio Graduation Test. More than 95 — sometimes 100 — percent of its students passed the math and reading tests required for graduation. Parents who shopped for regional high schools rated “excellent” could choose from Walnut Hills, Sycamore, Indian Hill and, among others, Taft.

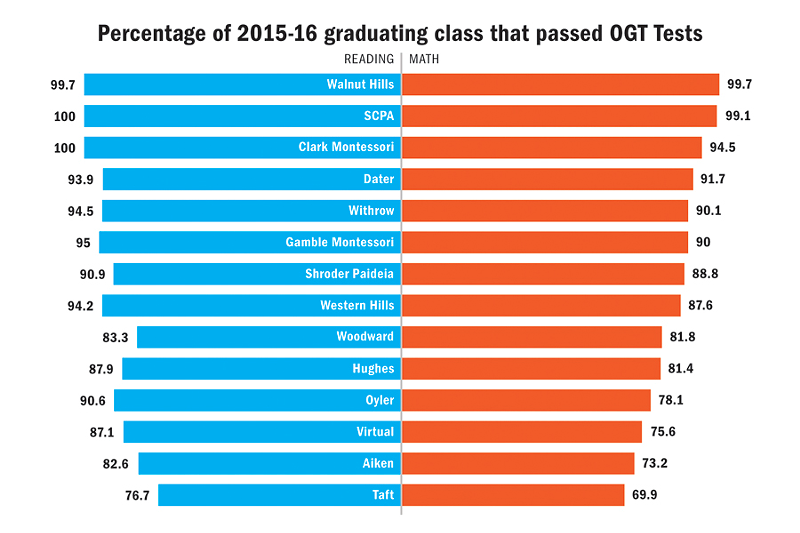

That was then. In the last two years of the OGT, Taft seniors had the lowest passage rate of the math and reading tests of every high school in Cincinnati Public Schools. Forget Walnut Hills and the School for Creative and Performing Arts; Taft is now behind Oyler, Aiken and Virtual. On its last Ohio report card, for 2015-16, the West End school scored straight Fs. Fewer than 70 percent of its students passed the OGT math test.

“If it’s a technology school, you would think they’re doing pretty good at math,” said Tom Fisher, an educational consultant in McMinnville, Tenn. “That’s challenging content, and math goes hand in hand with technology. I don’t know how they could succeed in their mission if they don’t have people who are more proficient in mathematics.”

Taft was awash in accolades at the turn of the decade. The Ohio Department of Education gave the school its first-ever “excellent” rating in 2010. Taft was hailed on the major news networks and American Public Media. It made the Christian Science Monitor, Education Week and at least two books, including Tom Brokaw’s “The Time of Our Lives.” Former Principal Anthony Smith was invited to speak at Harvard University. The cherry-and-whipped-cream topper came from the federal government itself when, in 2010, the U.S. Department of Education made Taft a National Blue Ribbon School.

So what happened? How did a school go from best-in-class to worst-in-class in a mere two years?

CPS won’t say. Outgoing Superintendent Mary Ronan, who called Taft a “classic comeback story” in 2010, refused to take questions from CityBeat. CPS instead offered up the district’s director of performance and accountability, Barbara Mattei-Smith. In a telephone interview, she expressed no awareness of Taft’s overnight collapse on the OGT. She says her focus is generally on district-wide data. On individual schools, she says she looks at broader indicators beyond OGT passage rates.

“Keep in mind that what I look at is 55 total schools,” says Mattei-Smith, a former associate director of ODE. “It’s not a matter of being aware or not, but a year after the fact, it’s not on the top of my head. I am so immersed right now in this year that I can’t answer questions about this without going back and pulling my files for last fall.”

CityBeat provided Mattei-Smith with Taft’s comparative OGT math and reading data, which are posted on ODE’s website, and awaited a callback. It never came. Instead, CPS sent a six-paragraph statement that offered no explanation of Taft’s 180-degree reversal. The statement says Taft has improved discipline, added two guidance counselors, opened a full-service health center and begun offering mental-health services. It says Taft is recruiting “top-notch” teachers, adding technology and now offering Advanced Placement and College Credit Plus classes. Taft students still receive tutoring from employees of Cincinnati Bell.

“At Taft IT High, as at other schools, the leadership and teaching staff are working hard to raise test scores and prepare students for success in college, careers and life,” the statement says.

CPS would take no further questions. “The statement is all we’re going to provide,” says spokeswoman Christine Wolff.

With one exception, members of the CPS Board of Education wouldn’t touch the subject of Taft’s decline. Three — Melanie Bates, Eve Bolton and Chris Nelms — were on the board when Taft achieved celebrity status. None responded to CityBeat e-mails sent them by the board office. Of the other four, only Daniel Minera responded, and since he joined the board in 2014, he wasn’t as familiar with the school.

Still, Minera says he was “absolutely” concerned about whatever happened at Taft.

“I think it’s a matter of looking at the schools, not only what’s happening at the classroom level but also at the community level,” he says. “We also have to look at the students and the families living around the school and the kind of support systems they have. Are they involved or engaged?”

Fisher, the educational consultant, says Taft’s dropoff on the OGT raises a host of questions.

“If scores decrease over time, it naturally would be necessary to determine what factors led to such declines,” he says. “Did the teaching staff change? Did the composition of the student body change? Did the curriculum change? Did the school administration change? Did the student/teacher ratio change? Did the local curriculum drift away from the state curriculum expectations? Did financial resources decrease?”

CityBeat called Taft to get the names of members of the school’s Local School Decision Making Committee (LSDMC) and Instructional Leadership Team (ILT) for parent feedback. Calls were forwarded to Principal Michael Turner. CityBeat left four voicemails for Turner but did not hear back from him.

How could a school have gone from abject deficiency to eight years of brilliance then back into the cellar? Some questioned its rise at the very beginning.

In 2006, the contractor that scored OGT answer sheets for the state reported a high erasure rate on the Taft tests that spring. The state asked CPS to investigate. Deputy Superintendent Laura Mitchell, who was just named superintendent for the 2017-18 school year, told the CPS school board that concerns about test improprieties were not substantiated. CPS pursued it no further.

But CityBeat gave the erasure analysis a closer look in 2012. It found that, of 1,707 instances where students had erased one multiple-choice answer for another, 88 percent went from wrong to right. Of the 26 erasures on one social studies question, all 26 went to the right answer. Of the 18 social studies test erasures by one 10th grader, all 18 went from wrong to right.

Smith told CityBeat at the time that the school told students to lightly pencil in answers when they weren’t sure, then go back and try them again. But two national testing experts said it was statistically unlikely for so many erasures to lead to correct answers.

“If you create a record of students making changes, the most common result is wrong to wrong,” said John Fremer, whose Utah-based Caveon Test Security did a forensic analysis in the infamous test-cheating scandal in Atlanta Public Schools in 2010.

The Ohio Department of Education continues to employ a company to conduct erasure analyses for the OGT. In response to a public records request for the analyses of Taft’s OGT results the last four years, an ODE spokeswoman said it had no such records. Why? Because Taft “was not flagged for excessive erasures” during that period.

CONTACT JAMES McNAIR: [email protected], 513-914-2736 or @jmacnews on Twitter