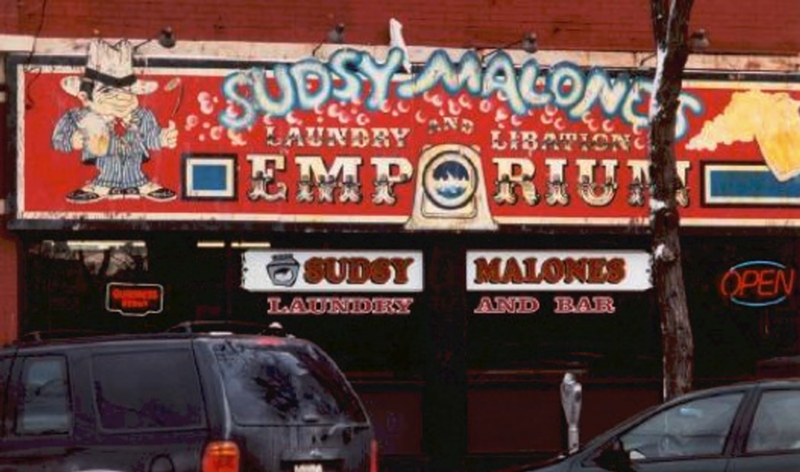

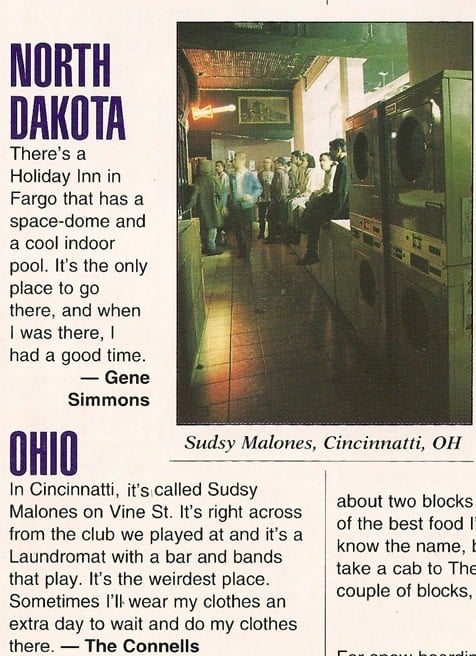

When researching Bogart’s for the first of these columns, I discovered a place that used to be its side-stream neighbor. Sudsy Malone’s, which sat just across the street from Bogart’s until 2008, may be a well-known name to older Cincinnatians, but to those of my generation I imagine it’s a legend unheard.

Sudsy’s, as those who knew it well referred to it, was more than just a bar or music venue. It was a laundromat. A gathering place of locals who fancied having a beer and hearing a tune as their clothes turned over in bubbly cleanliness. And while it was only open for a fraction of the time many of the big venues around here have been, it occupies a deep space in the history of Cincinnati and its local music scene.

Refined searches and several page scrolls through Google turns up hardly anything on the former venue. I finally found a memorial Facebook page that further fascinated me, still only offering a brief and general history but filled with posts by former loyal patrons reminiscing of great times at the bar, offering tales of hilarious happenings along with images, videos and old posters to fill it all in with color.

I wanted to know more in hopes of giving Sudsy’s its due place in Cincinnati music history. To understand where it all started and where it went from there, I talked to Janine Walz, a former managing partner who was around during the establishment’s heyday.

Sudsy’s was originally owned by John Cioffi and opened in 1986. As I understand it, the idea was inspired by similar businesses popping up in the region such as Dirty Dungarees in Columbus. They serve beer, so you can sip some foam while listening to the groan of washers and dryers, but Dungaree’s was never quite a bar. They served drinks in more of a refreshment center style. Cioffi’s vision for Sudsy’s was different.

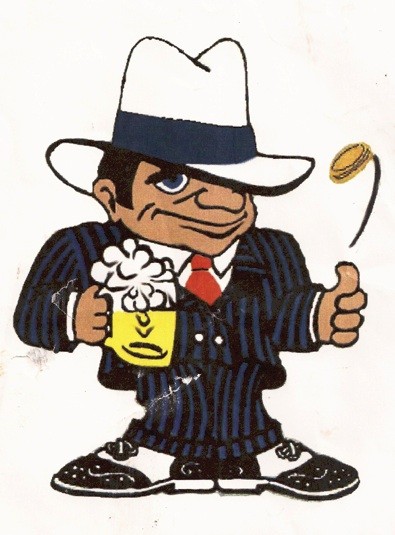

The decision for the name came from a lot of scrawling and scratching by Cioffi and his family.

“They just had a long list of names that they would write down as they were brainstorming, and then they started crossing names out until it was down to Soapy Tucker’s or Sudsy Malone’s,” Walz says.

Michael Sharp, the highly adored Renaissance man known for his ballet career in Cincinnati and who sadly just passed away in September, designed the character logos. Soapy Tucker was a sort of motherly figure, whereas Sudsy Malone was a true gangster.

He became the face of the place, with his one-eyed look, suds-filled beer and coin-flipping hand becoming the calling card of the bar’s sign.

Upon walking in the front door guests faced a 40-foot bar.

“We would have competitions to see who could slide a mug full of beer the furthest down the bar without spilling it,” Walz recalls with a smile.

They had little round cocktail tables covered with dark blue tablecloths and standard bar stools. The ceiling undulated with the movement of fans under which each had a globular light, providing a sort of soft ambiance to the bar.

At the back of the building sat the laundry area, a brightly lit room where the fluorescent lights glinted off dozens of top-of-the-line washers and dryers.

“I remember some of the bands complaining after a while about the laundry room lights because they would glow into the bar and kill the mood for the crowd,” Walz says. “We strung up some Christmas lights and would just turn those on instead when bands were on stage at night.”

When the place first opened, however, the stage didn’t exist. Live music had never even been part of the idea.

“It was only intended to be a laundromat with frosty-mug beer,” Walz says of the original plan.

Walz recalls being the second laundry customer when Sudsy’s first opened. She worked at the Perkins just up Short Vine, and happened to be John Cioffi’s waitress the day he sat down to get food with the liquor agent that was supposed to be approving Sudsy’s license.

“When they were finishing lunch he asked me to come a few doors down to talk to him about a job,” she says. “I figured it was the same distance from home and might pay better, so I went. Next thing I knew I was hired on as a manager.”

In other words, she was there from the start. Walz watched the bar being built, and she knew it when it was just a place for people to wash clothes and have a drink, the crowd rarely exceeding 10 people.

Only months after the place opened, a local band called The Thangs approached the owners with the idea to play music. Essentially, they just wanted a place to gig when nowhere else would let them. After some hesitation, Sudsy’s let them do it, and much to their surprise the first show was packed with about 100 people. Sudsy’s wasn’t expecting this, and they completely sold out of every drop of beer they had stocked at the time.

With such outrageous success, The Thangs wanted to come back. Before long, music became the detergent to Sudsy’s suds, responsible for consistently bringing in large crowds. At first they charged a very minimal cover, mostly so they had something to give the band, and offered a free soft-drink ticket with entry for additional incentive.

By ’87 they were charging a $5 cover, although they would still let people in for free if they had a basket of laundry. This often resulted in washers full of abandoned clothes the next day, as people brought the clothes to get in and then simply forgot about them in the excitement of music and merriment. Over time, Sudsy’s developed a massive collection of forsaken threads.

This memory sparked another for Walz: “I remember this guy that would show up about once every year driving a station wagon. He would take the clothes people had left over time and pack every inch of his car, literally. He would do something with them, I think donate them.”

As the place continually packed in people like foam to the top of a mug — thanks to the highly praised booking magic of Dan McCabe (Now of MOTR Pub) — problems inevitably occurred that now seem laughable. The carpet in the bar area became so matted and disgusting that it resembled tile, so Walz had it ripped out and replaced with wood. The men’s bathroom was a story of its own. Widely known as “Worst Men’s Bathroom,” Walz said she wouldn’t go near it, even almost buying stainless steel sheets to layer on it so she could just hose it down at night.

At one point the fire department came in and completely cleared house, although there wasn’t a single flame or wisp of smoke. The building’s stated capacity was far under how many people they would pack in, and one night they had to count the crowd back in, one by one. Eventually they completely stopped the music for a period of time to get the building up to code.

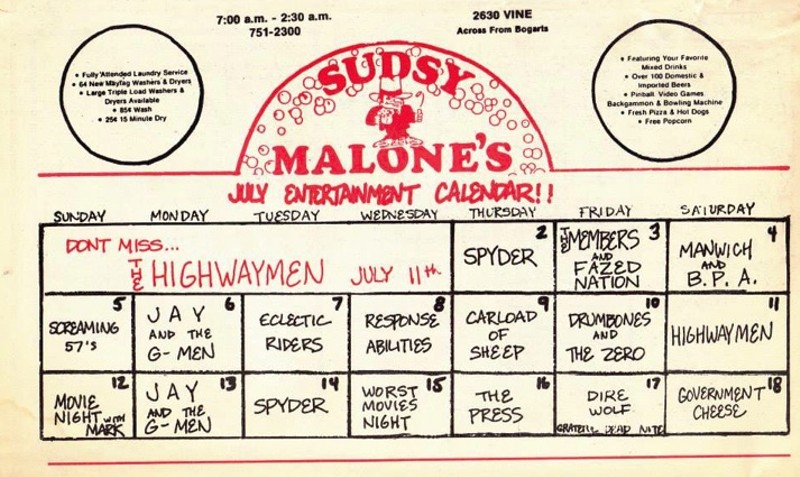

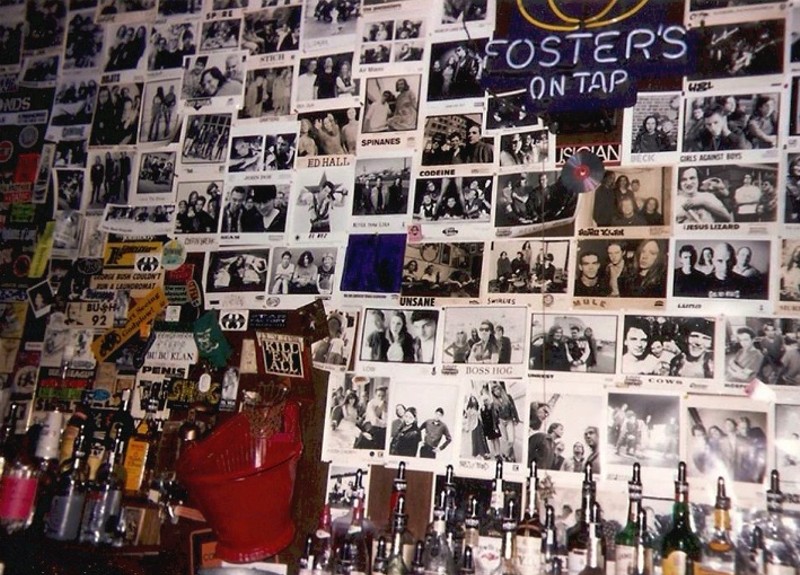

Despite its small size, Sudsy’s brought in now-major acts that were rising at the time — Beck, Smashing Pumpkins and Red Hot Chili Peppers — while also helping breed local acts like The Afghan Whigs and Over The Rhine. Almost all the music was original, save some special events like Grateful Dead night.

Even on nights they weren’t playing themselves, members of bands could always be found among the crowd. The music scene at the time was like a circle, made up of bands and fans that truly appreciated music and enjoyed simply watching people express themselves creatively. Bands would come out and support other bands. Non-musicians would out come and support them all.

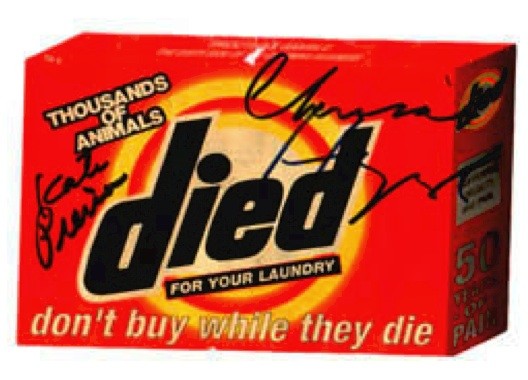

Even bands and celebrities that were too big to play there live in the storybooks. Popularly known folks like Jackson Browne, "Weird Al" Yankovic and James Taylor stopped in to wash clothes or use the phone. Kate Pierson (B52s) and Chrissie Hynde (The Pretenders) came by during their Tide protest to pass out literature in affiliation with People for the Ethical Treatment of Animals.

Walz recalls the afternoon before a Jefferson Airplane concert at Riverbend when the bar was pretty empty and there were four guys hanging out doing laundry and drinking a beer. They were worried about their cab not showing up and frantically trying to figure out how to get to their hotel — so Walz drove them. Only after dropping them off did she realize the reason the dudes were so worried about being late.

Walz showed me the blueprint of the building, and again lit up when she pointed out the wash sink in the laundry room.

“Some crazy celebrity took a bath in that sink one night,” she says. “I’m pretty sure it was Marilyn Manson.”

And these stop-ins aren’t the only “celebrity” claims to fame for Sudsy’s. The bar itself was given awards throughout the years from Cincinnati’s former alternative weekly Everybody’s News, from “Best Looking Staff” to “Best Rock Club,” and even “Best Place to Ditch a Blind Date.” They were also named the best bar in Ohio in ’93 by Creem magazine, courtesy of The Connells.

However, all the press, awards and celebrities aside, Walz says what really made the place special were the local patrons.

“It was like a family, people were loyal,” she says. “They would look out for others, and for the bands, and would always defend Sudsy’s no matter what. Without the people, everybody, the people that watched the bands, the bands themselves, Sudsy’s was nothing.”

The bar would even cater specifically to bands they knew well, for example stocking extra Hudy Delight when The Thangs would come back because their crowd loved to drink it.

There were also folks she referred to as “family bums”. There was Archie Harrison, a local homeless man who would help clean at night for a little money. During the days he would just hang out, always being jolly and telling jokes sharing what little bit of anything he might have had that day to share.

Then there was Sonny, a good-hearted man who hid behind a hulk of a body. Sonny would guard the back door, despite never being asked.

“I remember one time one of the dryers was broken and the glass wasn’t in there to cover the hole,” she says. “We had an out of order sign but, you know, I guess it disappeared. No surprise there. Anyway, we had given him some money to do laundry and he used that dryer, just picking up the clothes as they fell out of hole and throwing them right back in. It was hysterical. When we asked him why he didn’t switch dryers he said he didn’t want to bother us and cause trouble.”

As the Millennium rolled around, a lot of the core patrons began settling down and showing up less often. The crime in the area would keep people away, and the decline in the laundry business lowered their numbers even further. Walz had just put $12,000 into a new sprinkler system, still trying to keep the building code-worth, but she, too, was moving toward settling down.

“I was pregnant at that pointm too, and I was just kind of done working in the bar business,” she says.

That, along with clashes between Walz and McCabe about making money versus booking acts that would be huge for the scene led to Walz selling the establishment by 2002.

While it seems that Sudsy’s wasn’t as glorious after that time as it once had been, the venue remained open until 2008, at which time it closed its doors for good. The old building at 2626 Vine Street remains a boarded up relic.

One of the most revealing things Walz said during our talk about Sudsy’s was, “If you were there, you were part of the reason you are here talking to me today.”

It saddens me that I didn’t have to opportunity to be there, but for all those who were, as well as for the others that might not have known what this place ever was, this is just a small piece of the big apple pie that was Sudsy Malone’s Rock n’ Roll Laundry & Bar.