April 7, 2001 forever changed Cincinnati.

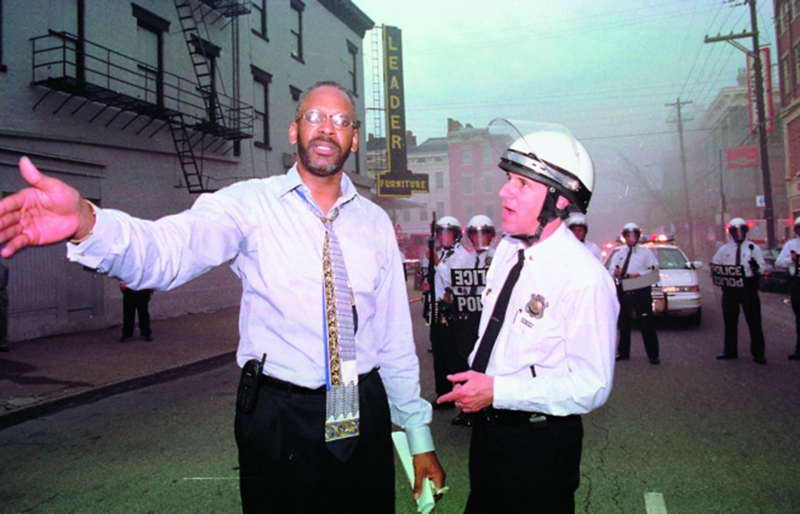

The police shooting death of unarmed black resident Timothy Thomas in Over-the-Rhine and subsequent unrest here 15 years ago presaged incidents in Baltimore, Ferguson, Mo., Chicago and elsewhere by more than a decade.

When other cities erupted with anger and fear over those more recent incidents, however, protests in Cincinnati remained peaceful and police left their riot gear at headquarters. Images of recent marches and rallies in Cincinnati present both an echo of and a contrast to the fitful reckoning that came after Thomas’ death in 2001.

A decade and a half after the unrest, many outside the city have lauded changes undertaken here. Cincinnati has been heralded by national publications like The New York Times, The Atlantic and others as a model for a nation experiencing a crisis around issues of police and race relations.

“The city that once served as a prime example of broken policing now stands as a model of effective reform,” reads an Atlantic article published last year.

Government task forces have also held Cincinnati up as an example of reform done right. Both President Barack Obama’s Task Force on 21st Century Policing, which visited Cincinnati, and Ohio Gov. John Kasich’s Taskforce on Community-Police Relations held up the city’s Collaborative Agreement and problem-oriented policing approach as worth emulating.

But data suggests there is much more work to do. Arrests and stops by police still fall disproportionately on black people here. The demographic makeup of area law enforcement agencies still doesn’t mirror the population they serve.

Controversial police-involved deaths continue to happen. And pervasive economic segregation in predominantly black neighborhoods continues to put stress on those communities. In fact, some critics say changes that have occurred in OTR since the unrest only underscore the city’s stubborn fault lines around race and economics.

Then and Now

The shooting of 19-year-old Thomas in OTR by Cincinnati police officer Stephen Roach strained long-standing tensions here to the breaking point.

Roach was white. Thomas was black. The incident shook Cincinnati, a city with racial tensions already churning.

During an emotional Cincinnati City Council meeting the evening after the shooting, Thomas’ mother Angela Leisure had a simple request.

“I demand to know why,” she said among a packed crowd of 200 angry protesters at City Hall.

From there, hundreds took to the streets during three days of civil unrest, seeking answers for Thomas’ death and the deaths of 15 other black men killed by CPD officers during the five years prior. Some posed an immediate threat to officers, CPD said. But three of those prior incidents involved unarmed residents. No white residents were killed by police in that time frame.

Long after the protests ended, after the curfews were lifted and after buildings that had been burned were rebuilt — in some cases replaced with shining new storefronts — the fateful shooting in a dark alley just off Republic Street has continued to have ripple effects.

A lawsuit against the city brought by local activists like Iris Roley and Rev. Damon Lynch III of the Black United Front, as well as the American Civil Liberties Union, resulted in federal oversight for CPD as it made reform efforts. Among those reforms: Cincinnati’s Collaborative Agreement, which is now hailed nationally as the gold standard in police reform.

The agreement created a framework for a more community-oriented kind of policing, better training and education for officers and increased oversight and accountability for police, among other reforms.

Time and struggles for reform have also changed attitudes.

“Without the civil unrest of 2001, the progress and change in our city, and the dramatic nature of the change, would have been less,” former Cincinnati Mayor Charlie Luken said recently at a Xavier University event about the unrest.

That’s a change in tone from those heady days in 2001, when Luken had harsh words for some of the protesters.

“Some of them seem to be out here just for the fun of it,” Luken remarked on a WCPO newscast at the time. “A lot of what I saw was not people reacting to the event … a lot of what I saw was 12-year-old kids stealing hot dogs from vendors and breaking windows.”

Cincinnati Police Department District 4 Captain Maris Herold says policing in Cincinnati has gotten remarkably better since the unrest. She touts the so-called “problem-oriented policing” approach that CPD adopted after 2001. That approach focuses policing on the small number of people committing crimes against a small number of victims in a couple dozen “hot spots” around the city.

“To me, everything is about strategy in policing, because policing is a paramilitary organization,” she says. “Prior to 2001 … basically, we were told to go out into the community with zero tolerance. When the community had complaints of violence, drug dealing, the overarching strategy was go out and arrest everything that moves. You could see it in the eyes of the people you were dealing with that this had horrible harm to the community.”

Arrest and use of force numbers show the effectiveness of the change in strategy, Herold and others say.

Use of force by police in Cincinnati has dropped nearly 70 percent in the past 15 years. Injuries sustained during encounters with officers have dropped by more than half. And the crime rate itself in the city has decreased by almost half as well — from more than 4,000 violent crimes in 2001 to just over 2,300 in 2014 — though some of that coincides with a large drop in crime since the 1990s in cities across the country.

But the reduction in crime and arrests isn’t the whole story.

“We’ve reduced arrests, but if you look at the percentages of black people getting arrested, it’s about the same,” says Cincinnati civil rights attorney Al Gerhardstein, who represented the Black United Front in its 2001 lawsuit.

Gerhardstein lauds the switch to problem-oriented policing, but he points out that 70 percent of felony and misdemeanor arrests still involve black people. Police arrest data for 2015 up to October of that year shows that 2,090 of CPD’s 2,936 felony arrests were of black residents. Of the department’s 13,447 misdemeanor arrestees, 9,430 were black.

That arrest disparity has proven stubborn. In 2001 and the years immediately after, the ratio of black residents arrested hovered around 77 percent. The rate has been as high as 83 percent as recently as 2013, and in 2014, black residents again accounted for 77 percent of felony arrests by CPD.

“We haven’t tackled that core problem,” Gerhardstein says of racial disparities in arrests.

Blacks also account for a similarly disproportionate percentage of the city’s crime victims, including homicides and other serious offenses. Many offenses happen in areas where low-income, mostly black residents have been concentrated by decades of policy decisions and market forces. Reams of studies show correlation between economic distress and crime in communities whether they are black or white.

Gerhardstein is hopeful about a new initiative that CPD has adopted this year called PIVOT, or Place-Based Investigations of Violent Offender Territories.

PIVOT is designed to further efforts like the Cincinnati Initiative to Reduce Violence, or CIRV, which started in 2007. PIVOT combines CIRV’s focus on the networks linking offenders and the community with data-driven, intensive attention on chronic crime locations that place-based policing pinpoints.

The key to the new approaches, Gerhardstein says, is engaging community stakeholders, including landlords, nearby businesses, neighborhood residents and others, and by changing environmental conditions such as lighting and traffic patterns that make locations more conducive to crime. If instituted properly, Gerhardstein believes PIVOT can further chip away at the number of arrests CPD makes and hopefully limit the disparities in those arrests as well.

But the reasons for those disparities are complex and larger than any one officer or department.

“So many young men of color become part of [the justice system] because so many minority families and communities are struggling... they lack all sorts of opportunities that most of us take for granted,” Federal Bureau of Investigation Director James Comey said in a speech on race and implicit bias in law enforcement at Georgetown University last year. Comey called that “a tragedy of American life — one that most citizens are able to drive around because it doesn’t touch them."

Continuing Tension and the Samuel DuBose Tragedy

The death of Samuel DuBose at the hands of University of Cincinnati police officer Ray Tensing last summer showed the extent of the problems that remain.

DuBose was killed July 19 after Tensing shot him in the head during a routine traffic stop in Mount Auburn over a missing front license plate. Though Tensing initially claimed he was dragged by DuBose’s car, footage from his body camera showed otherwise.

Currently, the UC Police Department is not covered by the city’s Collaborative Agreement.

Within 10 days of the shooting, Hamilton County Prosecutor Joe Deters announced an indictment of Tensing on murder and manslaughter charges. He will stand trial for those charges in October.

UC fired Tensing and reached an almost $5 million settlement with DuBose’s family. The department’s police chief, Jason Goodrich, also resigned earlier this year.

Despite the quicker move to indict Tensing — it took a month to indict Roach in 2001 — many in the black community say DuBose’s shooting is a stark reminder of the work left to be done.

“Even in 2015, some lessons have continued to escape us,” Southwest Ohio Urban League CEO Donna Jones Baker told a crowd at a Xavier University program on the unrest held recently. “We mourn the death of Mr. DuBose. There is no reason he should have died.

“In many respects, even given the many successes we’ve had with the Collaborative Agreement, we still don’t have it right. In my opinion, if the agreement was good enough for CPD and the citizens of Cincinnati, it should be good enough for any and all police agencies in Cincinnati, including our universities and the Hamilton County Sheriff’s Department.”

If UCPD had not been utilizing body cameras, DuBose’s death would still be shrouded in questions. That’s an important point because CPD has yet to fully adopt body cameras.

Questions around other cases involving CPD in the last year, including the police shooting deaths of QuanDavier Hicks in Northside last summer and Paul Gaston in Cheviot earlier this year, highlight continuing tension and underscore the need for the cameras.

Police said Hicks came to the door of his apartment building with a rifle after a woman filed complaints he was threatening her. An officer shot him and he subsequently died.

Gaston was on his knees in the street surrounded by officers after a chase in February when police say he made a motion toward his waist. Police say he was reaching for a weapon, forcing them to fire upon him. It turned out to be a toy. A bystander’s video taken from behind Gaston shows him making a motion, but does not show the weapon or shed light on whether he was reaching for it.

Activists and family members dispute police versions of events in both cases.

CPD is set to start phasing in body cameras this summer, but there are questions at the state level about whether footage will be public record. Cincinnati City Manager Harry Black last year signed a letter asking state lawmakers to keep the footage from being covered under public records laws. He has since rescinded that letter. State lawmakers are still working on laws around body camera footage.

Another aspect of the DuBose shooting illustrates a bigger dynamic at play. That a minor infraction led to DuBose’s death is a tragically familiar story. In 2001, police pursued Thomas because he had about a dozen misdemeanor warrants for traffic and other minor offenses. Like Thomas, DuBose was in a low-income, predominantly black neighborhood at the time of his death.

Statistics show such stops for minor incidents still fall disproportionately on black citizens in those neighborhoods.

UCPD issued 62 percent of its traffic tickets to black motorists in 2015, and Tensing himself gave black motorists 81 percent of the tickets he issued. UC’s campus is about 8 percent black, though the surrounding neighborhoods have a much higher percentage.

CPD stops for minor offenses also still fall disproportionately on blacks.

In 2015, 64 percent of those stopped by CPD for pedestrian violations and 63 percent stopped for traffic violations were black, according to department data. The city’s overall population is 46 percent black. Many of those stops came in predominantly black neighborhoods.

The department caught some criticism for its enforcement of minor offenses last month when Chris Harrell, who is black, recorded his Feb. 6 arrest for a pedestrian violation on Elder Street in northern OTR. That video subsequently went viral.

“This is what we have to go through in Cincinnati,” Harrell says in the video, pointing his camera behind him to show bicycle officers following him. “Harassment. Can’t even be a black man and enjoy your morning because the police are going to harass you.”

In the video, Harrell is walking with a cup of coffee and a cellphone as officer Baron Osterman trails him on a bicycle. At one point, the officer says Harrell crossed against a traffic light, though Harrell says the light had already turned and the walk signal had come on. Osterman eventually arrested Harrell, who was subsequently charged with resisting arrest, a pedestrian violation and a minor drug charge for possession of less than 100 grams of marijuana.

Officials with the city’s Citizen Complaint Authority, created as part of the Collaborative Agreement, have noted the disparities in who is stopped for minor offenses.

“We see many cases where citizens are pulled over for minor infractions for which I have never been stopped,” former Citizen Complaint Authority Board Chair Scott Knox wrote in the authority’s 2014 annual report. “I do not believe that any significant number of officers get up in the morning thinking, ‘I’ll pull over people based on their race today,’ but what I see is a disproportionate number of African-American citizens pulled over for minor infractions.”

The demographics within CPD also have yet to reflect the community it serves. Overall, the makeup of CPD has budged little since the 2001 unrest. Back then, 287, or 28 percent, of the city’s 1,028 officers were black. Today, 314 of the city’s 1,056 officers are. That’s a little less than 30 percent of the force in a city that is 46 percent black.

CPD supporters say there has been progress in this area at CPD, pointing to three black officers recently promoted to captain in the department and the fact that the city’s last three police chiefs, including current Chief Eliot Isaac, have been black.

High-Profile Incidents and Accountability Questions

Beyond the demographic numbers, there are still questions about how officers are disciplined when they break rules, both within and outside of the complaint process.

The Citizens Complaint Authority is supposed to be a first step in that process for those who feel like police have wronged them. The authority, which is made up of a five-member board, investigates complaints about use of force, harassment, improper procedures, discourtesy and lack of service. But it hasn’t been as high-profile as it could be, some say.

“It’s just not very present in our lives,” says Gerhardstein, who calls the CCA somewhat “invisible.”

Last year, the Citizen Complaint Authority hired a new director, Kim Neal, who has made it a mission to get the agency out into the community more. Neal and other CCA officials have spent time visiting the city’s 52 community councils and speaking with citizens who are unaware of the Citizen Complaint Authority or unsure about what it does.

Citizen complaints against police have dropped more than 40 percent from 15 years ago. But in the past five years, allegations lodged with the CCA have stayed more or less steady. There were 561 allegations in 2010, 596 in 2012 and 556 in 2014, according to CCA reports.

During that time frame, of the 650 cases investigated (not all allegations were investigated by the CCA, and some complaints contained multiple allegations), 62 were sustained, or turned over to the Cincinnati police chief.

How complaints are handled by CPD is somewhat unclear, however, an issue Neal says she is working on.

“That’s what the community wants to know,” she told WCPO last year. “If these allegations are sustained, people want to know what’s happening to the officers. … Is the police department listening to you?”

The Citizen Complaint Authority keeps lists of officers who have received more than 10 complaints in a two-year period.

Among the officers who have appeared on this list are Zachary Sterbling and Erich Kohler, two of the three officers involved in the Gaston shooting in Cheviot earlier this year. Police officials have ruled that shooting justified.

Sterbling had 10 complaints with 17 allegations between 2012 and 2014, while Kohler had 11 complaints with 14 allegations between 2011 and 2013. Both have also made the list in other years.

Other officers involved in high-profile police killings have also had questionable incidents on their records outside the Citizen Complaint Authority’s complaint process.

Last year, two Cincinnati police officers were charged in the coverup of a car accident involving a third officer, Sgt. Andrew Mitchell. In 2011, Mitchell shot and killed local musician David “Bones” Hebert, who was white, in Northside after police said Hebert was brandishing a sword. Later investigations revealed he had only a knife and that there was inconclusive evidence to show he meant to attack or threaten officers.

According to court documents, Mitchell was off duty and driving his personal vehicle, a Honda Odyssey, on West McMicken Avenue in Fairview at 5 a.m. on March 22, 2015 when he ran into a pole. Afterward, the two other officers allegedly concealed Mitchell from witnesses, helped him get home and did not fully investigate the accident, according to charges against the three in Hamilton County Municipal Court.

A witness at the scene of the accident called 911, reporting that Mitchell seemed “drunk as hell,” but no sobriety test was administered.

A Hamilton County Court judge dismissed the charges earlier this year, saying the matter should be dealt with internally by CPD. It’s unclear what, if any, penalties were levied against the three officers as a result of the allegations.

Mitchell’s shooting of Hebert in 2011 was controversial, causing a number of protests and investigations in Cincinnati. The shooting led to a 2012 wrongful death lawsuit against CPD. That lawsuit claimed Hebert was complying with instructions given by an investigating officer when Mitchell shot him. CPD settled that suit last year for $187,000.

That wasn’t the only incident involving Mitchell. In January of 2008, he was the subject of a civil rights suit after he allegedly used a Taser improperly against a teenager. Mitchell allegedly Tased Christopher Bauer from his police cruiser after he asked Bauer to stop. However, the teen was wearing headphones and a hoodie and didn’t hear the command. Bauer’s suit says he fell face forward and sustained substantial injuries during the incident. Mitchell was eventually placed on a 40-hour suspension after exhausting appeals within the department’s disciplinary system.

Some CPD officers once involved in controversial deaths — and with other past disciplinary incidents — have been promoted to supervisory roles. Earlier this year, CPD officials promoted Officer Patrick Caton to the rank of lieutenant.

Caton was involved in the Nov. 7, 2000 death of an unarmed 29-year-old black man named Roger Owensby, a Marine veteran with no criminal record or warrants, in Roselawn. Caton and another officer, Robert Jorg, pulled over Owensby for questioning, they said, when he tried to flee. A struggle ensued, during which Owensby was tackled, taken to the ground and choked and punched while handcuffed. He subsequently died in the back of the police cruiser. In later interviews and testimony, Caton admitted to punching Owensby both on the ground and in the cruiser, saying he did so with the palm of his hand so he wouldn't break his fingers and because it caused more pain.

Owensby’s death contributed to the racial tensions in the city that came to a head in April 2001. Caton was initially cleared in the incident but was fired at the conclusion of an internal investigation in 2003 for his behavior during the arrest. He later regained his job through arbitration.

CPD did not respond to a request for comment on Caton’s recent promotion.

Caton’s personnel file, obtained through a public records request, features a number of glowing reviews from superiors. But he has also had other disciplinary incidents, including a reprimand for using racial slurs while on duty, for which he was briefly suspended.

There have been other tragic incidents with a controversial lack of disciplinary outcomes at CPD. In 2010, prior to the massive revitalization of OTR’s Washingont Park, Cincinnati police officer Marty Polk accidentally ran over and killed Joann Burton there. Burton was laying under a blanket when Polk drove his cruiser through the grass, hitting and killing her. Polk faced no charges for the incident, which drew ire from some social service providers in OTR.

Economic Roots of Unrest

Despite continued questions around policing in Cincinnati, both police and activists say reforms like the Collaborative Agreement have been a worthwhile effort.

“It still has relevance to the peoples’ lives,” says Black United Front activist Iris Roley. “Children want to know — what did the people do for them? This is what we left for them to continue to fix.”

But activists like Roley also say the anger that erupted during the 2001 unrest was about more than policing.

“The original ask from the clients was about economic justice,” Gerhardstein said of the Black United Front’s original complaints that led to the Collaborative Agreement. “I sue people. I can’t sue capitalism. So we picked a bite-sized piece that was still tough enough.”

The economic complaints aren’t unique to Cincinnati, and they’ve sparked unrest in other deeply segregated cities across the country.

Dr. Maliq Matthew, a sociology professor at the University of Cincinnati, told CityBeat last year that recent unrest in Ferguson and Baltimore, like Cincinnati’s unrest in 2001, stretches back through decades of systemic inequalities.

“Really, these communities have been under pressure the whole time,” Matthew says. “These communities don’t carry a lot of political power and financial status. They erupt because they’re appealing to a power structure that they feel doesn’t hear them, that has no reason to really consider them.”

When it comes to those factors, Cincinnati still has a long way to go, as CityBeat explored in a story last year (“That Which Divides Us,” issue of August 26, 2015) outlining Census data that shows the disturbing extent of the economic isolation in Cincinnati’s black neighborhoods.

A few notable points:

• Of the city’s 10 neighborhoods with the lowest median incomes, nine are more than 70-percent black. Six of those neighborhoods with considerable populations, including the West End and Avondale, are more than 90-percent black. In these places, life expectancies are five to 10 years lower than the city as a whole.

• Citywide, the median income for blacks in 2013 was $21,300. It was $48,000 for whites. That gap has been widening. In 2000, the median income for white city residents was $36,452; for blacks, it was $20,984. In 13 years, whites in Cincinnati have gained $11,000 in median income, while blacks have gained just $316.

• Overall, 46 percent of the city’s black residents live in poverty, compared to just 23 percent of whites, according to the 2012 American Community Survey by the U.S. Census Bureau.

The economic gaps between blacks and whites in Cincinnati start young and linger. The city has one of the highest childhood poverty rates in the country, with many more black children than white living in poverty.

The disparities continue as children grow up. Despite being in a city that is 46 percent black, the University of Cincinnati’s student body on its flagship campus is just 8 percent black, for example.

These inequities have dire, though slow-simmering, consequences, racial justice activists say.

“Childhood poverty is not going to cause the next major civil unrest, but a police shooting will,” says Rev. Damon Lynch III, another activist instrumental in bringing about the Collaborative Agreement. “It won’t be because our police force is just that bad, but because we allow all those other issues to fester. It’ll come to a head when the next unarmed black person is shot or beaten by police.”

There have been efforts to address these disparities — an initiative looking to extend preschool to all of Cincinnati’s children, new development aimed at low-income residents in neighborhoods like Avondale and the city’s recently created Department of Economic Inclusion, for instance. But for many, the progress has been achingly slow.

Ironically, some say efforts to remake Over-the-Rhine in the wake of the 2001 unrest demonstrate the deeper economic and social divides still present here.

Ongoing Development in OTR

Today, the spot where Thomas died looks vastly different than it did 15 years ago, surrounded by boutique shops, gated parking lots and glittering restaurants standing in place of more humble establishments and vacant buildings.

Following the unrest in OTR, then-mayor Luken worked with a cadre of the city’s business leaders to form what would become the Cincinnati Center City Development Corporation (3CDC). Founded in 2003, it has since poured more than $400 million into the neighborhood and an equal amount into neighboring downtown.

The development it has quarterbacked in OTR — a historically low-income, mostly black neighborhood — has brought a rush of activity and investment there.

Some call it unmistakable progress, with lower crime, new businesses, more middle-class and upper-income housing and restored historic buildings.

But there’s a downside, others say.

Longtime residents are being pushed out of the neighborhood, advocates say, as developers renovate historic buildings and raise new structures for high-rent apartments and condos that can cost $500,000 or more.

For decades, OTR has been majority black, a holdover of the city’s demolition of a large part of the West End in the 1960s, which caused many blacks to move east into the neighborhood.

But recent Census data suggests this is changing in some parts of the neighborhood that have seen large-scale redevelopment.

Otis Stevens, a long-time business owner in the community, says he thinks blacks have been locked out of the resurgence in OTR.

“First, there was no money,” Stevens says. “We were trying to create jobs and development, a vibrant, self-sustaining community, but there was no money. Everything moves slow when you’re talking about fairness and opportunity. But then all of a sudden, in Over-the-Rhine, things are in warp speed, money falling from everywhere.”

Xavier University’s Community Building Institute on Jan. 25 released a housing inventory commissioned by the Over-the-Rhine Community Council of the housing stock in the quickly developing neighborhood.

The study, which uses Census data and current apartment price information, found that housing for middle-class and higher-income residents has increased. But at the same time, the most affordable housing — units costing about $400 for a one bedroom — has decreased by 73 percent, going from 3,235 units in 2000 to just 869 in 2015. Such affordable housing now accounts for about 22 percent of the neighborhood’s housing stock.

South of Liberty Street, the median household income for the once-impoverished neighborhood is now $40,000 and rising, according to 2010 Census data. North of Liberty, where little development has occurred, the median income is just $11,000.

The Census tract encompassing the southern part of the neighborhood, where most development has occurred in areas like the Gateway Quarter, was nearly 60 percent black just a few years ago, according to the 2010 five-year aggregate American Community Survey. The tract’s population rose from just over 700 that year to more than 1,000 three years later, according to the ACS, but the black population dropped by about 100 during that time, accounting for just 36 percent of the neighborhood by 2013.

The other Census tract south of Liberty Street saw similar changes over that time, and as many as 1400 black residents left the neighborhood between 2000 and 2010, according to a recent Greater Cincinnati Urban League report, even as new white residents moved in. ACS data suggests that change has increased in the years since, with the number of black residents decreasing sharply as white residents increase somewhat.

The ACS isn’t as precise as the 10-year Census, and the changes can’t be definitively attributed to gentrification. But the data seems to show a clear decrease in black residents in the area.

“I feel like my wagon’s surrounded, like I’m the last Mohican,” Stevens says. “I’m 53 now. I started out climbing on these buildings when I was 16. I’ve been trying to do development all my life. Where is the money coming from? Can we get access to it? Where do we get the help that we need to start businesses that reflect the community?”

The answers to those questions lie beyond police reforms, but they’re intimately tied to the trauma OTR experienced 15 years ago.

For some, the neighborhood continues to be a bitter reminder of inequalities in the justice system and beyond.

“I spent 25 years of my life in Over-the-Rhine,” says Rev. Lynch, whose New Prospect Baptist Church once stood on the corner of Elm and Findlay streets. Lynch’s church has since moved to Roselawn. “I lost. I left feeling defeated. I left there with people who raised their kids and grandkids. We keep losing because we don’t take the next step. The economic fight is the fight we have to fight.” ©

More:

"Violence as a Health Issue: Re-Framing Safety, Re-Thinking Policing, & Adjusting the Cincinnati Collaborative Agreement," a conference on the aftermath of the 2001 unrest and continued issues in policing and race relations, will be held April 11-16 at New Prospect Baptist Church, 1580 Summit Ave. in Roselawn. The event is free and is sponsored by the AMOS Project, the Hamilton County Office of Reentry, Cincinnati Metropolitan Housing Authority, the Ohio Transformation Fund, the Black United Front and others.

The schedule:

April 11, 6-8 p.m.

UC Police update on Samuel DuBose

April 12, 7-10 p.m.

Screening, Cincinnati Goddamn documentary

April 13, 7-10 p.m.

Screening, 3 1/2 Minutes, 10 Bullets documentary

April 14, 6-10 p.m.

Conference opening celebration

April 15, 8 a.m. - 8 p.m.

Policing: Where We Are Now

April 16, 9 a.m. - 4 p.m.

The Future: Rebuilding, Retooling, and Getting to Work

More information/registration: www.communityandpolicerelations.com or call (513) 800 6925.