T

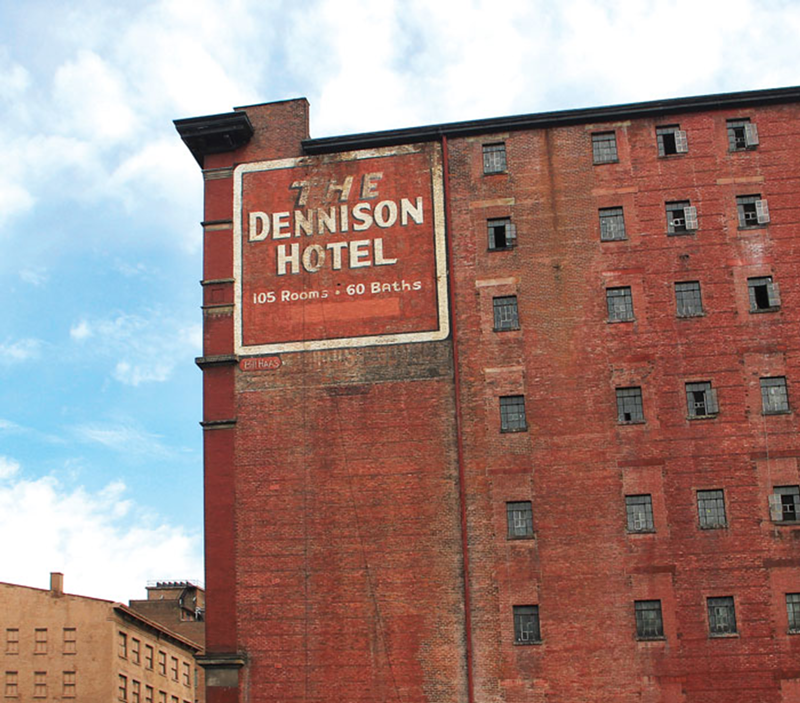

he contested fate of a historic building downtown is in the hands of an appointed seven-member board — and that makes preservationists nervous.

Dennison Hotel owners the Joseph family say it’s not economically feasible to save the building. Preservationists disagree. So does the city’s urban conservator, who issued a report last month highly critical of plans to demolish the Dennison.

But the final decision is in hands of the city’s Historic Conservation Board, which will vote on the demolition May 26. Some preservation advocates claim that the board’s deck is stacked in favor of developers friendly to Mayor John Cranley, who is in turn friendly with the building’s owners. Cranley denies this.

The board’s decisive role in the Dennison Hotel’s fate illustrates the importance and fraught politics of the numerous boards and commissions appointed by Cincinnati’s mayor and city manager.

Board appointments are commonplace, and appointing qualified political allies is legal. But campaign finance data highlights the political connections of appointees on some city boards.

A CityBeat analysis of board appointments and campaign contribution data shows the majority of the more than 200 board appointments made by Cranley or City Manager Harry Black have not been Cranley campaign donors. But some who now sit on important boards gave big to Cranley’s 2013 mayoral campaign or past City Council campaigns.

Roughly $32,000 of the more than $1 million Cranley raised for his mayoral campaign came from 40 individuals who were later appointed to boards, and another $16,000 came from the spouses or parents of those appointees. Appointees gave about $7,500 to Roxanne Qualls, Cranley’s opponent in that election.

A spokesperson for the mayor did not provide answers to questions about the appointment of Cranley allies to city boards before this story went to press. In the past, however, Cranley has said that the appointments are standard practice.

“Every administration makes new appointments to boards,” he told The Cincinnati Enquirer last year about the Historic Conservation Board. “It’s not surprising there are changes. The people who the city manager has appointed have a balance of historic conservation and economic development.”

There are currently 37 boards to which the mayor can appoint members. These range from the Cincinnati Board of Health — one of the city’s oldest, established in 1832 by a City Council ordinance, to which the mayor appoints all nine members — to the Ohio-Kentucky-Indiana Regional Council of Governments, to which the mayor can make one appointment. Board appointees don’t get paid for their service, but do wield influence.

The city manager appoints members to another 19 boards, including the Historic Conservation Board, created in 1980 by a City Council ordinance. Cranley picked Black for the city manager position, and he was approved by City Council in 2014. He’s often hewn closely to the mayor’s vision for the city.

The Dennison tussle is not the first time city boards have been a source of controversy. Last year, consternation swirled around the city’s Park Board after revelations that the board donated $200,000 to the campaign for Issue 22, a parks tax levy championed by Cranley. That money, from the board’s private fundraising foundation, was later returned to the board.

Concerns about the Park Board deepened with revelations that it had spent millions on the construction of Smale Riverfront Park without putting contracts out for bid.

Park Board head Willie Carden is a Cranley ally who the mayor in 2013 floated as his choice for city manager. Cranley has appointed only one member to the board — Diane Rosenberg, who donated to his campaign — and reappointed another, Susan Castellini. Rosenberg and her husband gave $4,400 combined to Cranley’s 2013 campaign, and Castellini, part of the powerful family that owns the Cincinnati Reds, gave $3,200.

The mayor came down hard on the board in the aftermath of the revelations, ordering a complete outside audit. Cranley has blamed the lax spending practices on former mayor Mark Mallory’s city manager, Milton Dohoney.

There have been other moments of contention involving city boards. Outgoing Cincinnati Board of Health Chair Joyce Kinley told Cincinnati City Council’s Budget and Finance Committee in March 2014 that she was not being reappointed to that board for political reasons.

“He told me he had to fulfill a campaign promise,” Kinley said of Cranley at the meeting, “That’s why he had to remove me.”

That year, Cranley appointed four members to the board of health, including campaign donors Gary Hagopian and Phil Lichtenstein. Hagopian and his wife gave Cranley’s 2013 campaign $3,300, while Lichtenstein gave $1,000. Both have also given thousands to Cranley’s City Council campaigns in past years. Hagopian is an attorney for Procter & Gamble, while Lichtenstein is a pediatrician and medical director at the Children’s Home of Cincinnati.

Now it’s the Historic Conservation Board’s turn for scrutiny. It’s in the middle of the pitched drama over the Dennison, designed in 1892 by the firm of noted Cincinnati architect Samuel Hannaford and owned by powerful Cincinnati car dealership family the Josephs.

Cincinnati Urban Conservator Beth Johnson issued a report last month staunchly siding with preservationists, citing the building’s overall sound structural condition and financing sources like historic preservation tax credits developers didn’t take into account.

Next week, the Historic Conservation Board will have the final say. That’s caused consternation among preservation activists.

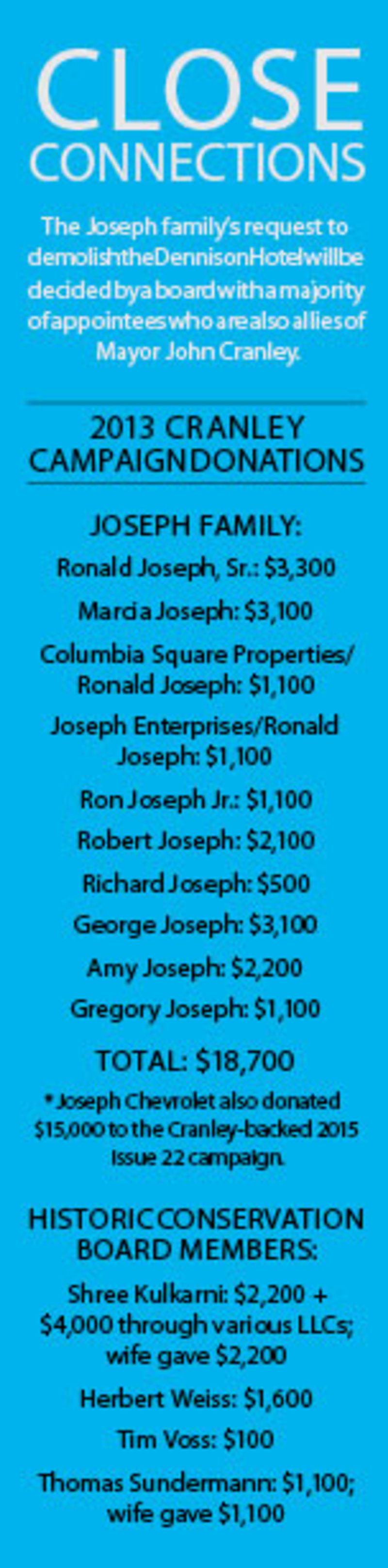

They cite the fact that several recently appointed board members are also Cranley allies, as are the Joseph family themselves. The Josephs have contributed about $34,000 to Cranley’s 2013 mayoral campaign and to last year’s Issue 22 park levy campaign, plus thousands more to his past City Council campaigns.

“That’s why they donate all the campaign finances that they do — so they get what they want,” preservation activist and Cranley critic Derek Bauman said last month about the Josephs in a video posted to Facebook. Bauman has also been critical of appointments to the Historic Conservation Board.

That board weighs in on questions about local, state and federal historic regulations on construction, demolition and renovation in the city’s 29 historic districts, often acting as the final “yes” or “no” on such projects. The Dennison, at 716 Main St., sits in one of those districts, called the Cincinnati East Manufacturing and Warehouse District.

Black, with Council’s approval, has appointed five of the Historic Conservation Board’s seven current members — Shree Kulkarni, Herbert Weiss, Tim Voss, Thomas Sundermann and Robert Zielasko. Of them, all but Zielasko made contributions to Cranley’s 2013 mayoral campaign, according to campaign finance records.

Kulkarni, the largest donor, gave $2,200 to Cranley’s campaign personally. He gave another $4,000 through his various LLCs. His wife, Kirsten, also gave $2,200. Weiss gave $1,600 to Cranley’s campaign. He’s a partner at Keating Muething and Klekamp, a downtown law firm where Cranley once worked whose political action committee was the mayor’s biggest donor in 2013. Sundermann and his wife both gave $1,100, and Voss gave $100. Kulkarni has been on the development end of preservation-related battles before. Previous to his term on the board, Kulkarni was responsible for the demolition of a downtown building preservationists argued was historic on Fifth Street.

In March, the board granted owners permission to demolish a building across the street from the Dennison at 719 Main St. The building was constructed in 1875 and also sits in the historic district.

Like with the Dennison, developers said preservation of the building would present a financial hardship to their efforts, an argument the Historic Conservation Board agreed with.

The Historic Conservation Board had a different outlook on another building in Over-the-Rhine in 2014, before the current crop of Black-appointed board members began their terms.

Several blocks north of the Dennison, at 1119-1123 Main St., the Davis Furniture building was at the center of a big fight in November of 2014 after owners the Stough Group sought permission to demolish the 100-year-old structure.

That led to a seven-hour fight at a Historic Conservation Board meeting. Eventually, the board turned down Stough’s application for demolition.

Now, preservationists and developers alike await the board’s May 26 decision around the Dennison. The Josephs say they’d like to use the property as part of a development that would lure a Fortune 500 company’s headquarters to Cincinnati.

Preservationists, however, cite interest from Pittsburgh-based developer Linden Street in buying and rehabilitating the building as proof it could be saved. ©