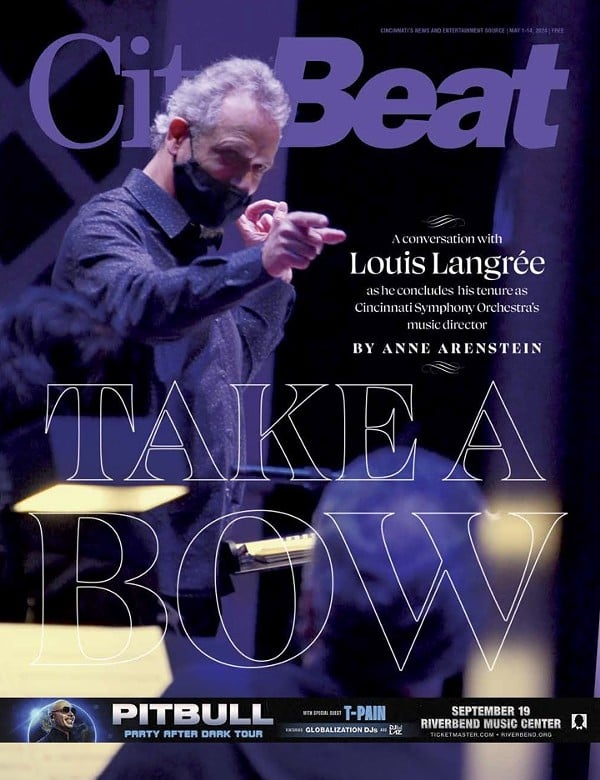

This story is featured in CityBeat's Oct. 18 print edition.

For years, Barney Killingsworth’s family thought he’d walked out on them. A cold, silent goodbye with no warning, no note, no regard for the life he’d left behind. But all along, he was in an unmarked grave in West Price Hill. All because of one typo.

“He was a DOA at General Hospital, they misspelled his name, so his body became a cadaver for the students,” says Sandy Rice, Killingsworth’s great-granddaughter. “They used him from 1944 to 1947 [when] his remains were cremated and interred at Potter’s Field. There’s over 5,000 who have stories like that.”

The certificate of death shows the clear, infuriating misspelling that left Rice’s family heartbroken and confused for years: Barney “Killingswrogh” was laid to rest at Cincinnati’s Potter’s Field Cemetery. Rice fell down a genealogy rabbit hole when she discovered the fate of Killingsworth, and she’s been free falling ever since.

“No one would take more than 10 years of their life identifying the burials of Potter’s Field,” Rice says, with well-earned certainty.

Welcome to Guerley Road

If the people of Potter’s Field were a neighborhood in Cincinnati, they’d be the third largest in the city, at 18,575 forever residents. Or at least that’s Rice’s most recent tally. It’s constantly in flux as she hovers over her iPad late into the night, filling out a spreadsheet with columns for names, place of death, causes of death — but if they’re on the spreadsheet, they’re in Potter’s.

A “potter's field” is a common historical term for a place where communities would bury the poor (otherwise called “indigent”), the unidentified, the incarcerated, infectious disease victims and others who were “unwanted.” In Cincinnati, the roughly 26-acre Potter’s Field stretches across the northwest side of Guerley Road into Rapid Run Park. We can glean that bodies were buried in straight lines from the few remaining grave markers; a small, flat stone with a metal plate, if they’re lucky, lists the deceased’s name and date of death. Some plates just display the plot number. Others were honored with a small wooden cross that nature would later swallow. Countless graves are completely unmarked, and many people are buried in stacks of three, one generation after the next, with the top burial resting a mere 18 inches beneath the surface: the height of an American Girl Doll.

There are other potter’s fields in the city, but none this big. The city says burials began here around 1852, but Rice has pinned a mother buried there with her baby in 1849. While time and place are important to Rice, the number of bodies beneath the surface, and who they are, is what keeps her up at night.

“I don’t sleep much,” Rice texts at 10:30 p.m. after logging 15 hours of research that day. “This is my mission.”

That mission has grown. These days, Rice, turning 57 in November, isn’t just attempting to document the burials in Potter’s Field. She’s also fighting for better conditions for the souls’ final resting place. It’s an effort that has earned her few friends at City Hall — spending years making countless calls, emails, records requests — and she can’t help but suspect that leaders have a secret plan for the site.

But it all begins with research. Helping in that work is Lynn Bereman.

“I met Sandy through Ancestry.com, she and my husband are distant cousins,” she says. “That’s how we connected.”

The pair decided Bereman would handle the earliest burials, starting in the mid-1800s, through the turn of the century — they’re working to compile a complete spreadsheet of every Potter’s Field burial.

“She knew how much I liked genealogy and asked me if I would want to help her with this project I’m working on,” Bereman says. “And I thought all I was going to be doing was compiling data and doing some research and helping her out; come to find out that it was much more intense and thought-provoking than I had anticipated.”

Gilded Age horror

Potter’s is in no short supply of shocking, well-documented tales, including those of notorious body-snatching resurrectionists who would unearth the dead for Cincinnati’s various medical colleges. But Bereman finds both thrill and comfort in the stories of average citizens who eventually found themselves in Potter’s.

“I found all walks of life,” she says. “Some professions I encountered were shoemakers, tailors, cigar makers — lots of cigar makers! So I started thinking, these are the people who built Cincinnati.”

Though Bereman lives in Indiana, she routinely visits Cincinnati through blurry records and documents, absorbing our local labor history like a thirsty sponge.

“A lot of the people I found were laborers in Germany or another country,” she says. “Then they got to the United States and carried on with their trade. It would be like ship building, working in shipyards, building infrastructure. Because remember, this was roughly 1850-1900, so, as the city was growing and building, these types of people were integral in that.”

With those Gilded Age jobs came injuries and fatalities. If your workplace hadn’t yet caught the union bug, you were likely risking your life with no safety net — physical or financial.

“There were a lot of industrial accidents, people falling off of buildings, falling into the river, and of course back then, there was no worker’s comp, no benefits for people to bury their loved ones with,” Bereman says. “Of course, with all the transients that came down through there, finding relatives was very difficult. So, after so many days, they just buried them in Potter’s Field.”

Bereman’s neat handwriting tracks just a handful of the deaths from her designated time frame. She’s assembled the varying pieces through death certificates, newspaper clippings, Ancestry.com — anything to match a name to a plot number:

- August Alakan, age 40; he was born in France in 1846 and died 40 years later in a railroad accident near Eastern Avenue. His grave number is 466.

- Agnes Archibald was only 22 when she died on Oct. 21, 1874, at City Hospital while giving birth. She was a seamstress. Her plot number is 320.

- Augusta Brehm was born in Germany in 1852; 30 years later she died in City Hospital from septicemia following an abortion. Her grave number is 140.

- A.F. Boch was murdered while performing an abortion in a bordello, also known as a “whorehouse.” He was just 31 when a blow to the head sent him to Potter’s. His grave marker is 153.

- Mike Callahan is the oldest on this particular sheet; he lived to 48 before he was parboiled in a vat of glycerine at Thomas Emory & Son’s candle factory at the “foot of Vine Street” on May 7, 1892. He’s in plot 291.

- George Williams, a Black man, was born in South Carolina in 1834. He was 40 when he died of tuberculosis at City Hospital. His grave number is 412.

- Ben Warfield, a Black Civil War vet, was born in Ohio in 1847, dying 30 years later at Good Samaritan Hospital from cholera. His grave number was also 412.

- Every child in the Laekamp family died of smallpox within days of one another in April 1882: twins Annie and Eddie, age 5, Louisa, 12, and Willie, 11. None of the Laekamp children are buried together.

“I did go in and do some research on [the children] for confirmation they were family members. Because they didn’t list that anywhere, just the last name and an address and that kind of tipped me off. I’ve since looked into census records,” Bereman says. “As one member got it then another member got it. It’s sad.”

Bereman pores over birth and death certificates, historical news articles and online services like findagrave.com to match a person to a plot, a necessary measure thanks to a fire that burned the cemetery’s records around 1890. Nevermind that most people buried in Potter’s don’t have a visible gravemarker to reference today; the area is completely overgrown and impossible to navigate. Bereman is preserving a history that feels like it was designed to be forgotten.

“I do feel a connection to them, very much so,” she says. “In the northern section alone there are 505 former slaves.”

New century, more records

With the turn of the century comes a different historical caretaker: Sandy Rice. A reset in the records collected by the sextons who looked after Potter’s Field opened up opportunities for Rice. While she, too, is a digital record-finding wiz, her real talent lies in cold calling.

She recalls locating a stack of Potter’s records at the Cincinnati Public Library.

“The records were at the county, they had to call an employee who retired to find out what happened to them,” Rice says. “The records were actually handed over to the library in 2009. The library did nothing with them, they stayed under a librarian's desk for 11 years. According to what I heard, she propped her feet on them.”

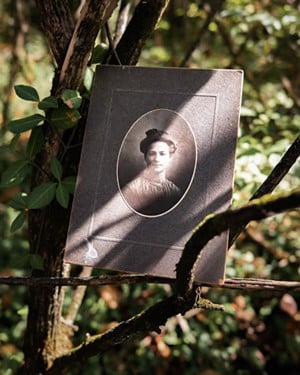

Records find a way of flowing toward Rice when she isn’t even asking for them, like when a descendant of a former sexton gave her a large stack of photos of Potter’s residents he’d come to collect over the years.

Once Rice began inching closer to the present in her pursuit to identify those in Potter’s, she started a Facebook group where she would chronicle her findings. She says 11% of the group’s 470 members are direct descendants of someone buried in Potter’s Field. Everyone is looking for someone.

Fannie Landman

Steven Pastor’s grandparents immigrated to Cincinnati from Austria. They lived in a small tenement with no private bathroom and no electricity. He was used to hearing stories of this time, but what happened to his aunt Fannie remained a mystery until Rice stepped in.

“As I’m growing up in the ‘50s, I learned that, in between my mother, who is the youngest, to my uncle Israel, who is the third, there was another daughter that died named Fannie Landman,” Pastor says. “My grandparents didn’t have the money to bury her. It was what we call in Yiddish a ‘shonda’ that they could not afford a Jewish burial. And my mother I guess learned of this at some time but nobody ever talked about it, because my grandparents were ashamed.”

Pastor’s aunts and uncles remember Fannie, but his mother was born long after Fannie’s death at age seven on Oct. 6, 1919.

“Her official cause of death was scarlet fever,” he says. “Realizing they had no funds to do this, the death certificate says she was buried in Lick Run Jewish and the undertaker was Weil-Schell Company at 1711 Race Street.”

In an effort to locate their aunt’s grave, Pastor, now 76, and his uncle Israel called Lick Run Jewish and the Weil-Schell Company.

“And for unbelievable reasons, they had no record of her. I tried numerous avenues but obviously Israel did everything I did and he couldn’t find any more information.”

Eventually, one of the Jewish cemeteries told Pastor to contact Rice — as she says local cemeteries often will when someone is having a hard time locating a loved one. She has an encyclopedic knowledge of Cincinnati’s cemeteries, and she’s not afraid to make phone calls on someone’s behalf.

“I checked all the cemeteries — not Catholic — just to make sure she wasn’t anywhere else: Baltimore Pike, Walnut Hills and Wesleyan Cemeteries I personally checked, all the Jewish cemeteries also,” she says.

After research and phone calls to confirm what the death certificate implied, Rice told Pastor she believed his aunt was in Potter’s Field.

“Remember, she was contagious and must be interred by nightfall,” Rice tells CityBeat.

Pastor was grateful for her sleuthing.

“I was just so impressed by her knowledge about Potter’s Field,” he says. “Her dedication to this is like God’s gift.”

Even so, he says, he was heartbroken to learn of his aunt’s likely resting place. He told CityBeat he’d feel differently about his aunt being in Potter’s if it looked even close to respectable.

“It made sense to me. It does,” he says. “But I’m certainly not satisfied with that because, well, have you been to Potter’s Field?”

Half of Potter’s Field was transformed into what’s known today as Rapid Run Park. Formerly known as Lick Run Park, Cincinnati City Council released half of Potter’s Field to the parks department in 1934. Renovations in the 1940s included the addition of a large man-made pond. Rice says that workers encountered human bones during the dig. Playgrounds and walkways have continued to pop up in the park over the years, but sporadic grave markers make it hard to know where someone’s final resting place ends and a child’s play place begins.

In stark contrast, the other half of Potter’s looks like something out of The Last of Us. Invasive plants like honeysuckle and non-native grape vines sprout thickly from the ivy-dense ground. A homeless encampment sits obscured by the dense overgrowth near where Rice says many veterans are buried. Trash dots varying sections of Potter’s, oftentimes left behind by curious wanderers or those seeking shelter. To find any remaining grave markers, one would need to search on hand and knees, or wait for winter to thin the thicket.

Pastor himself hasn’t been to Potter’s, but he’s heartbroken by the stories of the tangled vines and neglect.

“It’s certainly not only insulting, it’s playing to people’s basic needs of their loved ones to be able to rest in peace and dignity. Of life. Life!”

Robert James Vaughn

Like in any cemetery, cancer sometimes got the best of best.

“My dad and I were very close,” Eileen Vaughn Glancy tells CityBeat. “We were best buddies. He was my rock.”

Glancy shares a picture with CityBeat of her girlhood self clutching her dad’s leg on the beach, the widest smile stretching to touch either side of her beach scarf.

“I love that picture,” Glancy says, now 68 years old, admiring the photo like it was her first time seeing it.

“My dad was part owner of Tiffany Photography Studios,” she says. “Dad would set me up at my own table, I was only 12, and dad would be at this other table and he would say, ‘Oh, you gotta buy this package! Look at this baby! Look at this little — aww, he’s so great!’”

Vaughn’s photography skills made him a valuable asset during multiple wars.

“In the Coast Guard and Navy, I think he started out with just portraits, then he went to the Marines for a period of four months and I think it had to be because of his photography skills,” Glancy says. “By WWII he was actually using the TriMech camera. He knew how to operate a camera in the air.”

It wasn’t until ‘72 that Vaughn needed to start thinking about how he’d prefer to use his body after his death.

“We found out in April of ‘72, they took him in for what they thought was hepatitis,” she says. “He was at Good Sam. They discovered he actually had bowel cancer that had traveled throughout his body. They closed him back up, said there was nothing they could do, and gave him three months to live.”

Glancy calls the reason her dad ended up in Potter’s the “million dollar question.”

“Dad’s brothers and I at the memorial service asked the attorney [...] for the return of dad’s ashes,” she says. “My dad’s brothers wanted to bury them in Paris, Illinois, the family plot. They had a grave for him.”

But Vaughn had made other plans. He donated his body to science — according to his daughter, so that “no one else would go through this.”

“Dad was keen on medical science,” she says.

“He was a huge figure in his siblings' life, in my life,” she says. “The brothers would call me about the situation with the ashes, and I would say, ‘I’ll call the attorney.’”

While Glancy’s mother took on the task of dealing with the finances around her dad’s death, Glancy assumed the task of locating the ashes once his body was no longer being used to teach medical students.

“This went on for about a year and four months,” she says.

Glancy continued to press the family attorney for answers about her dad’s ashes — no one told her the medical college could use cadavers for more than two years. She says their attorney and the college were aware they wanted his ashes returned to the family for a proper burial at the family plot, but by the summer of ‘73, Glancy says their attorney informed her the ashes had been lost.

She had entered high school with her best friend, but by the time she was packing her bags for college in England to study archeology, he had disappeared. Like her dad had done so many times before in the service, she was bravely hopping on a plane for an adventure to uncover stories. But it would be decades before she came to know the end of his.

After stumbling upon Rice’s Potter’s Field Facebook group, Glancy’s cousin Phillis confirmed her uncle’s ashes were buried in Potter’s Field with the help of records Rice obtained from the University of Cincinnati; these records are not normally available to the public. UC’s Department of Medical Education, like most anatomical departments, would bury the cremains of their cadavers in large groups in Potter’s, sometimes in paper bags or pine boxes, many with no marker in sight to this day. Starting in 1985, UC’s Body Donation Program began burying cremains in the beautiful and beloved Spring Grove Cemetery. There, families of lost loved ones can visit a monument identified by the inscription, "Through Their Thoughtfulness Knowledge Grows." The college holds an annual memorial service for those who gave over their body to science, complete with speakers of varying faiths; a choir sings angelically while a projector rolls through images of the deceased.

Vaughn received no such honor reaching his final resting place. Nearly 50 years after Glancy clutched her dad’s leg on the beach, she finally knew where her dad was; she just couldn’t get through the thicket to find him.

“I probably cried for months. I had a hard time communicating at all,” Glancy says. “I was totally devastated because of his service for his country, the person that he was.”

The grief ate away at Glancy imagining her dad in a mass grave, one that is practically inaccessible due to overgrowth. She says Rice showed her compassion.

“Sandy was very comforting to me,” she says. “I talked to her in tears, just totally broke up that after 50 years, that my dad, who was in every branch of the service, who was larger than life, was in Potter’s Field.”

In the months following the news, Glancy slowly came to accept her dad’s final resting place. She theorizes that her dad wouldn’t necessarily mind being in Potter’s. It was a slight peace of mind that she says took four months to accept.

“I had decided that dad, being religious as he was, would think, ‘I’m not there anymore, my spirit is with God, I don’t want my ashes found,’ you know? I had come to grips with that,” she says. “I thought well, dad was not one to be prejudiced or judge or think that he was any better than anyone else.”

Sue Stone

Like Rice, Sue Stone believes it was a misspelling (and a miscarriage of justice) that ended up putting her grandfather’s ashes in Potter’s.

“None of my family knew he was there. My mother was three years old when he went into Longview (Insane Asylum). She never knew, she had four sisters,” she says.

Stone’s mother, her four sisters and their father, Charles Agustus Wise, lived in an apartment behind Findlay Market when Stone says her grandfather was taken from his home and involuntarily committed at Longview Hospital in 1927.

“He had come home one day and he told my grandmother that someone was chasing him, some guys were chasing him,” Stone says. “He was afraid, so he went to his apartment, got his gun and said he could hear their voices outside, so he shot out his window, out the bedroom window. Someone had called the police from a call box down the street, so the police said, ‘We have to take him for observation.’”

Stone says her grandfather was given a choice: three days in jail or three days in Longview. Hindsight suggests he would have fared better in jail.

“They took him to Longview Hospital, and he never got out,” Stone says.

While the family knew Wise was taken to Longview, there was confusion over his whereabouts after what was supposed to be his third and final day as a ward of the state. Stone says he died in Longview on Sept. 16, 1955.

“Nobody knew where he was,” she says. “It was not just me by myself. My mother always wanted to know where her father was. After my mother passed away, we knew how much grief it caused our mother throughout the years. So, my brother, my sister and one of my cousins, we took it upon ourselves to look for our grandfather.”

Letters, phone calls and scouring the internet eventually lead Stone to hire an attorney to help locate her grandfather’s remains.

“She wrote letters to Longview, because that’s the only place we knew that he was supposed to have gone to,” Stone says. “They say yes, that they did have him out there, that they did send [his body] to the anatomical department, and that they did notify the family. They did not notify the family. My grandmother lived at the same location for 25 years before she moved from those apartments because she was getting old herself. She moved in with one of her daughters over in Sayler Park.”

The failure to connect Wise with his family started with a clerical error, according to Stone. She says another Longview patient’s last name was spelled “Weisse.” That name, according to Stone, stuck with Wise, making it impossible for his family to get any answers from the hospital.

After working with their attorney to find out Wise was always in Longview, Stone’s brother visited the hospital where he met a reverend who claimed to know Wise.

“This reverend told my brother and my sister that he built all the furniture and tables in Longview,” Stone says.

Wise, an educated carpenter, had never before displayed any signs of mental illness or distress, according to Sue.

“When we questioned him,” Stone says. “‘Why did you keep him? What was wrong with him? Why did he stay so long?’ and he said that there’s nothing in the ledger.”

At 73 years old, the anger in Stone’s voice cuts sharply through the phone lines that stretch from Ohio to her new home in Texas.

“They diagnosed him with nothing,” she says.

What’s next for Potter’s?

As Rice’s efforts make more people aware of the loved ones and distant ancestors buried in Potter’s Field, many of them start to take the condition of the burial ground personally.

As for Stone, she isn’t just passionate about Potter’s, she’s angry.

“This is where my grandfather is buried, I should be able to walk up to his grave to pay my respects. I don’t ask anymore or any less than any of you that go to the cemetery to visit your loved one,” she says.

Glancy wants to see something done to the area to give its forever residents the respect they deserve.

“Wouldn’t it be wonderful if Cincinnati honored the Potter’s Field? Put some money in the budget for Potter’s,” she says. “It seems like the City of Cincinnati is like, ‘Um, we don’t really care,’ you know? Just kind of let it go.”

Granting hope

But taking care of long-neglected gravesites is seldom a municipal priority. Dead people, after all, don’t vote. And while the city has made some efforts in recent years, not everyone is happy about the pace of progress or the plans.

After Potter’s stopped accepting bodies in 1981, the onus fell to the City of Cincinnati to handle landscape maintenance, but only the park that sits atop graves has received any attention. In 2022, more than 30 years after Potter’s last burial, Cincinnati Parks green-lit an archaeological assessment to start the process of determining the scope and density of bodies in Potter’s Field. Cincinnati Parks did not pay for the project — it was funded by a History of Equal Rights (HER) grant from the Historic Preservation Fund, administered by the National Parks Service.

The $34,694 grant was secured in May 2022 by Mike Morgan, an attorney, adjunct horticulture instructor at University of Cincinnati and local beer history expert. It was through Price Hill Will, a nonprofit community development corporation, that Morgan secured the grant. He tells CityBeat it’s rare for any city’s potter’s field to receive such a grant, let alone any federal dollars.

“I mean, other cities have done things and struggled with [their own] potter's fields,” Morgan says. “I'm not aware of anybody else getting one of those grants to work on a potter's field.”

The appeal for funds, according to Morgan, focused particularly on the economic disadvantages that led so many to end up in Cincinnati’s Potter’s Field, and the long-lasting, shameful treatment of their final resting place.

“There are two pools of federal money, one dedicated to African American civil rights, [the other] dedicated to equal rights in a more broad sense,” Morgan says. “The nature of the grant application was the disparity of how people buried at the site have been treated, in comparison to how we as a society, treat our dead generally.”

Archaeological fact-finding

The HER grant project ended up looking like something between a conservation assessment and a crime scene being processed.

Beginning the week of Oct. 18, 2022, the Archaeological Research Institute (ARI), a nonprofit based out of Lawrenceburg, Indiana, initiated three different types of search methods in varying zones of Potter’s to begin determining the approximate location of human remains.

Pedestrian survey: This search assessed what could be observed on the surface, noting that “local lore” suggests human remains have been seen coming out of the ground’s surface due to years of erosion. This search didn’t find conclusive evidence of superficial bones, but it did note “sloughing” of some visible grave markers due to “natural gravitational pull.”

Human Remains Detection (HRD) Dogs: In areas where ground cover was especially thick, K9 search dogs were brought in to help identify the presence of decomposed bodies. The report notes that HRD dogs are most commonly used in forensic cases to pinpoint the recently deceased, but says these dogs have shown “promising results” in recent archaeological searches. As expected, the dogs made nearly 100 “hits” that indicated the presence of human remains. These hits were made in highly pared down areas that do not represent the entire scope of the park, in part because of the presence of “unsecured” dogs in the homeless encampment that often pops up in the sloped wooded area between the park and Guerley Road. According to the report, this presented a “concern for the safety of personnel and the HRD K9s.” The report noted this was “unfortunate” since the area is near where the former sexton’s house once stood.

Geophysical Survey: Moving beyond what can be observed with human eyes or a canine’s nose, a geophysical survey used technology to identify variations in soil distribution to indicate a burial. But the report says findings from magnetometers, ground penetrating radars and electromagnetic induction meters supported the known history of Potter’s Field by what the technology couldn’t find. While not everyone who was interred in Potter’s was indigent, everyone got the poor man’s burial. The unceremonious discarding of bodies in simple pine boxes, coupled with the wild overgrowth in many parts of the park, meant people decomposed quickly along with their coffin.

While the geographical search didn’t offer a detailed map of those buried in Potter’s, Morgan found beauty in the explanation.

“You could look at it as green burial today,” Morgan says. “As a result of that, the dogs would always hit on the trees because the root system actually pulls up those scents that come from the erosion of the people buried there. It’s really kind of beautiful to walk there and think that those trees, you know, those are kind of the monument. Those trees are thousands of forgotten people.”

Rice, along with Stone, expressed deep mistrust with both the ARI site survey and the intentions of everyone involved.

“They penetrated the ground with rods! They know these burials are 18 inches deep, most of them, because the ground has been turned five times. But they’re jabbing rods into the ground? I’m sorry, that’s desecration,” Rice says.

The survey was coined as ‘Phase 1’ because, at the time, Morgan and others hoped the preliminary results would be a starting point for a more just, respectful resting place for the forgotten people of Potter’s.

“This project was entirely part of a first step to a better understanding so that then you could begin to have community conversations about what to do with the site,” Morgan says. “That was the entirety of that project.”

But nearly a year after the study began, the city and Morgan tell CityBeat there are no plans for any continuation of the project at this time.

In an email sent to Rice after she lodged many complaints and records requests on the subject, Jason Barron, director of Cincinnati Parks, told Rice nothing whatsoever is planned for Potter’s Field.

“The reality is that we do not have anything to provide beyond what has been provided. And the simple reason for that is that we have NO PLANS to develop Potter’s Field,” Barron says in the email. “There is no phase 2 or 3 or 4. And as such, we cannot produce something that does not exist. We also do not have anyone working on any plans.”

While Morgan does not work for the city, he echoed these claims, saying, “The city’s not going to do anything now. They’re not going to spend a dime on Potter’s Field. They didn’t care about it before. They cared about it for about 10 minutes when all of this was very positive and then when they had to start dedicating staff time to constant phone calls and emails and Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) requests, they became hostile to the concept.”

Morgan is referring to Rice. He says his academic experience in horticultural design and passion for Potter’s informed his desire to connect community members who wanted a more dignified Potter’s Field. He told CityBeat he found Rice’s ongoing research on those buried in the cemetery to be a highly valuable asset, but that conversations broke down when Rice demonstrated deep mistrust in many involved in the budding project.

“The city has told me it wouldn’t matter if I showed up with a million dollars in federal funding, the number of FOIA requests that she files around Potter’s Field make doing anything to improve it untenable,” Morgan says.

In an email Rice forwarded to CityBeat from Cincinnati City Manager Sheryl Long, Long tells Rice the two have reached an impasse.

“While all citizens are permitted and encouraged to participate in the Park Board’s planning process, it has been noted that over the years city staff, in addition to the mayor, council members and my office, have received repeated phone calls and emails from you regarding the cemetery,” Long writes. “Staff has frequently spent up to an hour or more with you on a single phone call, often discussing previously addressed issues/concerns.”

When asked if the city has any current or future plans for Potter’s Field, Long’s office told CityBeat in an email: “There are no plans to develop or change Potter’s Field.”

Rice flatly disbelieves the city’s words.

“Nothing right now from the city I trust. Nothing. They’ve hidden and lied,” Rice says. “They’ve already gone over and called Potter’s Field ‘Rapid Run Park,’ you can go on the CAGIS system and see that.”

Stone, who is in lockstep with Rice, also doesn’t buy it.

“They are doing something, they are making improvements and they aren’t going to do it for no reason,” Stone says. “I don’t believe what he is stating, I think there’s a bigger picture here.”

To Rice and Stone, that “bigger picture” comes in the form of an expanded Rapid Run Park, worries about commercial development and theories that those involved will line their pockets in the process.

Morgan tells CityBeat that, technically, the city has every legal right to build what they want on top of Potter’s Field — not that he wants them to exercise that power.

“There is no inherent protection for what you do to a non-active cemetery,” Morgan says. “Which means that the city could do whatever it wants, which is why this project was important to me to make sure that from a decency standpoint, that didn't happen.”

Historical future

The results of the HER grant project have been used to apply for Potter’s to be included in the National Park Service's Historical Register. The Register represents the nation's areas of historical and cultural significance worthy of preservation. Morgan says historical designations are commonly assumed to protect historic buildings, but a cemetery in need of care is different.

“When it comes to guidelines and standards, we’re going to have to see what that looks like, because it’s going to be a much looser standard than you would have for a perfectly intact 1820s building, because of the nature of the site and the history of the site,” Morgan says. “The state is not going to get in the way of restoring it, improving it, removing weeds from it, but the state would have a problem with doing things that are just clearly inappropriate and disrespectful to its use and history as a cemetery.”

For now, Bereman and Rice are continuing their pursuit of identifying as many of the souls buried at Potter’s Field as possible. They look forward to having enough data to quantify and publish the demographics of those resting beneath West Price Hill’s feet.

“Eventually, we will be able to tell how many died of a certain thing, how many came from a certain country, how many different races, other demographics like professions,” Bereman says.

As for Rice, she will continue to connect families with their loved ones, fighting for answers about Potter’s and for respectful maintenance to the final resting place they now call home.

“All of us want the same thing,” Rice says. “We’d like to see the cemetery put back into a state of respect.”

Subscribe to CityBeat newsletters.Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed