When Cincinnati Opera’s production of Porgy and Bess opens on July 20, it will do so for only the second time in the company’s 99-year history. Composed by George Gershwin, with a libretto by DuBose Heyward — the author of the play Porgy upon which the opera is based — and Ira Gershwin, Porgy and Bess premiered in 1935 and is regarded as a seminal American folk opera, and the first to feature African-Americans in all singing roles.

“To put it in perspective, Porgy and Bess put on by opera houses is still a recent phenomenon. It doesn’t really enter the repertoire of core opera houses in this country until 1976,” says Cincinnati Opera Artistic Director Evans Mirageas. “And it’s partly the fault of the snobbery of the American Classical music establishment (because) they considered Porgy and Bess to be this hybrid between an opera and a Broadway musical.”

Under Mirageas’ leadership, Porgy and Bess made its company debut in 2012. This upcoming production (July 20, 25, 27 and 28) is new and features costumes by Hamilton costume designer Paul Tazewell.

Set on Catfish Row in Charleston, South Carolina, Porgy and Bess is the tragic love story between Porgy, a disabled beggar, and Bess, a woman with another complicated love affair and a “happy dust” habit. The residents of Catfish Row round out the cast, creating a well-realized community that allows both Porgy and Bess to dream, fight and come face to face with their respective realities.

George Gershwin specified that all singing roles be performed by African-Americans, which gave many a prodigious start to various opera careers; Leontyne Price, the heralded Metropolitan Opera star, is one such example. But as is the danger in any art form, sometimes performers were only cast in Porgy and Bess.

“It is taught to you early on that the further you can stay away from (roles like Porgy), the less likely it is that you’re typecast as those for the rest of your career,” says Morris Robinson, who portrays Porgy in the Cincinnati Opera production. “Because once you, as I say, jump on Catfish Row, it’s hard to get off Catfish Row. So I wanted to make sure that I diversified myself; I established myself firmly in standard repertoire.”

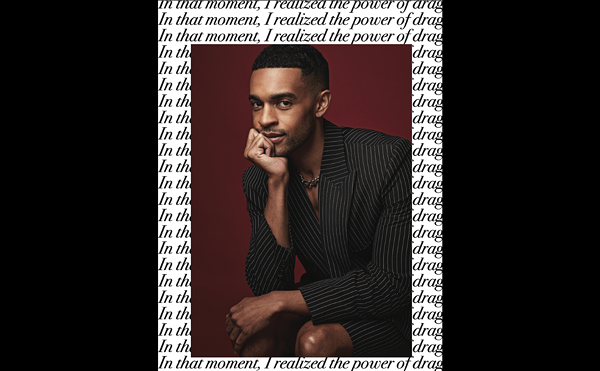

Robinson’s path to opera was unconventional: a former high school and college football star, he went on to sales in corporate America. A lifelong love of music and fondness for singing blossomed after an audition for the Choral Arts Society in Washington, D.C. led to a solo and his first operatic role as the king in Aida. More training followed, which quickly led to what is now a full-blown, seven-language-spanning international career.

He took on the role of Porgy in 2016, some 17 years after he started performing opera, following a phone call from the famed La Scala opera house in Italy. Robinson says this performance was then followed by eight other offers.

“I think with Porgy and Bess, you can fall into the trap of, ‘Oh, here comes the number we know, that was our favorite song.’ I think it needs to still feel raw and immediate,” says Talise Trevigne, who is making her Cincinnati Opera debut performing the role of Bess.

Criticisms of Porgy and Bess extend beyond song familiarity, pointing to linguistic and character stereotypes and portrayals.

“There are lots of people who write about Porgy and Bess — some very, very famous African-American historians and performers of generations past — who say, ‘it’s a travesty,’ that ‘it disses our people,’ that ‘it should not be done,’ ” Mirageas says.

“Whereas, when you talk to people like Morris and Talise, they say the best way to remove those stereotypes is perform it with grace and power and passion,” he continues. “The controversy will rage for as long as the piece is produced. But I’ve come to really strongly believe that if you have performers who are engaged with a piece, it will tell its story in a very honest and powerful way.”

As Cincinnati Opera approaches its 100th anniversary next season, the company has expanded its efforts to engage and diversify both its audiences and its performers, as have a multitude of legacy arts organizations the country over. Since Robinson was first brought onboard in 2017 as Cincinnati Opera’s artistic advisor, he has made diversity a priority.

“I find that people are attracted to that with which they’re familiar,” Robinson says. “To diversify your audience base, you have to diversify the product you’re offering not only in terms of repertoire, but also in presentation and the people behind the pitch.”

Trevigne agrees. Post-singing career, she says she wants to continue working in opera and ensure that directors, singers, conductors and women of color all have a seat at the table.

“I think that is the next step the arts need to go in — because they’re there and they just haven’t been given the opportunities, and so they haven’t been heard,” she says. “It’s going to take risk. But I think it’s one that ultimately will be rewarded for greatly.”

To that end, Cincinnati Opera is making great progress. Blind Injustice, a world premiere inspired by the Ohio Innocence Project, is composed by Scott Davenport Richards, an African-American composer. The opera is already sold-out and opens later in July. Next season, the company’s centennial sees the world premiere of Castor & Patience, with a libretto by Tracy K. Smith, the African-American 2017 U.S. poet laureate.

Porgy and Bess opens July 20 at Music Hall with performance dates through July 28. Tickets/more info: cincinnatiopera.org.