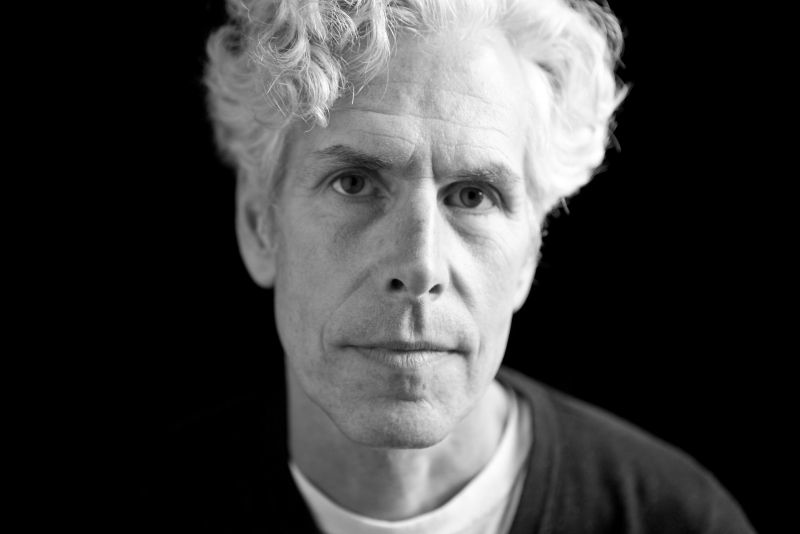

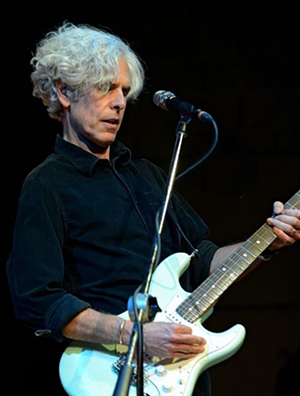

Rob Fetters has rightly achieved iconic status within the Cincinnati music scene, as befits a master Pop/Rock craftsman whose resume boasts bands the Raisins, the Bears, psychodots and an impressive solo career. More importantly, his nationwide run of house concerts in 2018 and his series of streaming shows during the pandemic have conclusively revealed his equally voluminous and fervent fan base in the wider world.

“I had to get over my fear of doing the livestreams, and playing a screaming ass song and then...crickets. No response,” says Fetters during a recent phone interview. “That's when my inner Bob Shreve kicked in. I learned to channel that and now I've got my own sound effects. It's like a crappy Ed Wood/Bob Shreve show. It's circus time, but I get to do music and the music is real.”

And yet, in casual conversation, Fetters will, in all honesty and humility, refer to himself as “a nobody.” He's had legitimate shots at the brass ring; a befuddled Clive Davis came to Cincinnati to see the Raisins and left without offering them a contract, perhaps a blessing in disguise.

And the Bears scored a deal with respected indie I.R.S. Records through their imprint Primitive Man Recording Company, whose PMRC acronym was an eyepoke at the Parents' Music Resource Center, a reactionary censorship cartel headed by outraged-hausfrau-with-benefits Tipper Gore. But the Bears only managed to release two superbly eccentric albums with PMRC before the label imploded, leaving the band to periodically resurface with self-released gems across the three subsequent decades.

With psychodots, Fetters and longtime cohorts Bob Nyswonger and Chris Arduser made a mighty Pop/Rock noise for 28 years off and on, keeping creative ambitions high and expectations for success at a reasonably low level. Just two years ago, the 'dots declared an end to their annual Thanksgiving shows in Dayton and Cincinnati with one last spectacular blowout at the Woodward Theater.

Finally, there's Fetters' solo catalog — three well-crafted albums released at relatively long intervals: 1998's Lefty Loosy Righty Tighty, 2005's Musician and 2014's Saint Ain't. Fetters' solo presence had been previously limited due to his burgeoning commercial music endeavors, but he has largely extricated himself from that end of the business to concentrate on his personal songwriting.

As with every musician on the planet, the pandemic provided Fetters with a surplus of time after his house concert schedule for 2020 was cleared, so it was hardly a shock when he announced the release of his fourth solo album, Ship Shake, in early December. The eyebrow-raising aspect of the album is that none of its material was actually written during lockdown.

“To tell you the truth, some of the leftovers were just so goddamned depressing,” Fetters says. “I figured I could have three sad songs on the album, maybe four. I've got some real sad pandemic songs, and I'll wait to release those. At some point, you just have to stop whining.”

It's astonishing that Ship Shake feels so contemporary when its themes and perspectives were shaped so long ago; Fetters has seemingly been writing for this moment in history for well over a decade. “Queer Year” feels as fresh as tomorrow's breaking news, and yet it was the first song Fetters wrote after completing Saint Ain't in 2014.

“A friend of mine came out and thought I'd be upset, and I was like, 'Aw, man, why would you think that?'" he says. "I didn't want something trendy and hip, I just wanted a statement of 'I love you, brother.”

The ostensible title song, “Turn This Ship Around,” was composed five years earlier.

“That song was so heartland Rock it embarrassed me,” Fetters says. “I took it to my friend Brian Lovely and he wrote different lyrics for it, trying to save it, but that wasn't right either so I buried it. In March, when stuff was starting to go bad, I was well into this album and I found 'Turn This Ship Around' and played it, and it was like, 'Whoa, this is totally now.' I had Bob play bass, and my son Noah was able to record drums on it, which he did for five other tracks. He's an audio/stage tech guy and I didn't know he could record himself that well, but he did a great job.”

Some songs on Ship Shake are older still. “Dog is God” was played by psychodots a couple of times, and “Not the End” was credited to the 'dots and appeared on the public radio fundraising disc Get Real Gone (“The only people who heard it paid $100 for the disc...so not a lot of people.”). The oldest original song on the album is “Artichoke,” a song that dates back to the Raisins — a live version appeared on the band's swan song, Everything and More, released on cassette in 1985 — and which was reimagined by the 'dots on their 1991 eponymous debut.

“I had no intention of re-recording that again, but when I did the house concerts, Bob and (former Raisins drummer) Bam Powell went into the studio with me to record bass and drums so I could play it at house shows,” Fetters says. “I play along to tracks, it's not unplugged Rob. I like acoustic music but I'd die the death of a thousand cuts if I had to be acoustic Rob all night. I like loud, electric music. I started playing 'Artichoke' and it was like, 'Whoa, this is swinging!' The psychodots version is good, but I felt like this was the real song.”

One of Ship Shake's more recent songs is “Me & Eve,” which Fetters wrote in 2017. It's also one of his most emotionally raw compositions, as the second verse begins with this sobering revelation: “I got molested when I was four/I talk about it now, it ain't a secret anymore.” Fetters didn't talk about the incident with anyone until he was in his mid-30s, not until his children triggered an overprotective response that required therapy to resolve. When the idea for “Me & Eve” began to evolve, it was an interesting take on the Garden of Eden story that took a harrowing turn.

“‘Me & Eve’ came out of nowhere,” Fetters says. “When I was gathering the songs for this album, I was thinking that I should call it Songs I Should Never Play in Public. I've always been irritated by Adam and Eve, that to have knowledge and a raised consciousness means you get banished. Somewhere in my mind, I wanted to write a song backward. You know, they start with their clothes on, eat the apple and then the clothes come off. Then I disclosed something; the second verse is totally autobiographical. I went into therapy and came to realize that trauma didn't define me and I became more comfortable talking about it.

"When I was doing the house concerts, I realized I was in an environment where I could get away with that one. I'm squeezed into a living room with 35 people and everyone's comfortable and I'd say, 'Can I play a heavy one? You want to go dark?' And generally, it'd be, 'Yeah, make it darker!' The first verse, people are giggling because it's funny, the second verse, jaws are dropping, third verse, we're OK. After that, I decided to record it, but not put it on a record. Then I recorded it, and it was too late, so I put it right in the middle of the record where maybe nobody would see it. It's probably the song on the album.”

Ship Shake is, in most respects, a textbook example of Fetters' artful craft. Sonically, the songs range from bracing and engaging Pop Rock (“Turn This Ship Around,” “Artichoke,”Can't Take It Back,” “Prophets,” “Dog is God”) to lilting balladry (“Scripture,” “Me & Eve,” “Not the End,” “Believed”).

Lyrically, the themes are typical Fetters fodder; the obscurity detailed in “Nobody Now” (“I loved that song when I wrote it, but I thought, 'Fuck, I'm writing another song about being a loser'”), the political prescience of “Prophets” (“I wrote that in 2016 when I suspected that Trump might win”), the lost love of “Believed” (“I wanted to write a song about the first time my heart got really broken. I played it for Noah and he cried. He said, 'Dad, you can't play that!'”), the found love of “Me & Eve,” and the resonant isolation of “Scripture” (“It just makes sense now because people are afraid to come outside”).

The oddball on the album is Fetters' cover of “Shakin' Street,” a slowed down but still scorching take on the MC5 classic, originally found on their 1970 sophomore album Back in the USA. Once again, Fetters' house gigs contributed to the song's inclusion on Ship Shake; he would regale his intimate audiences with tales of his early life and going to Detroit to see concerts, which would include recollections of the Stooges and MC5. When they blanked on the MC5, he would remind them of “Kick Out the Jams” and then hit them with an acoustic cover of “Shakin' Street.”

“I've always loved that song and I loved playing it on an acoustic guitar,” Fetters says. “So I thought, 'Nobody's heard this, let me record it and see what happens.' My version is a lot swingier than the MC5. It's slower but it rocks.”

Fetters admits that Ship Shake would likely have been delayed a year or more because of his packed house concert schedule, but he remains hesitant about identifying his latest solo work as a pandemic album.

“I think I've realized that artists take pain and turn it into something beautiful,” he says. “Not always. Sometimes it's fun to come up with ‘Guernica.’ But we take trauma and try to make sense of it by putting it into a song.”

With Fetters, the dichotomies stack up pretty quickly. He's a self-proclaimed nobody who is enough of a somebody to book himself into living rooms from coast to coast. He can write about the dissipated Rock lifestyle from memory, secure his status as a dedicated family man, and create eccentrically accessible Pop songs in between catchy commercial jingles for United Dairy Farmers and LaRosa's. He's a lapsed Methodist who adheres to no religion and even claims a relative lack of spirituality, an agnostic bordering on atheism that sings about faith and God with equal amounts of passionate conviction and questioning cynicism. And yet he believes in a higher consciousness, or perhaps it's a lower consciousness, and most of all, he believes in his family, his friends and his art.

“I get to do my work and that's all I need,” Fetters says. “I get to eat, I've got a roof and I get to do my shit. I am so grateful to the people who support me, they're so wonderful. In a weird way, maybe I am trying to be a holy man, to take all my pain and experience and do something good with it. Todd Rundgren had his album Healing, and you're damn right, he's a healer. Wayne Kramer, Pete Townsend, Chuck Cleaver, you are motherfucking healers. Kate Wakefield, you're a healer. All these people are holy to me, and this is what I'm supposed to do.”

Learn more about Rob Fetters at robfetters.net and listen to Ship Shake at robfetters.bandcamp.com.