A triangular building with a huge clock atop it overlooks Vine Street in Cincinnati. Inside, the walls are lined in fabric, rugs and thick curtains to help dampen the sound. Flickering candles on triangular tables provide a wavering low light, painting the room with an intimate atmosphere.

For the last two decades, jazz pianist Ed Moss could be found sitting at the piano in the front of the room, face in the keys. This club, Schwartz’s Point, was his passion project.

Moss died in 2016 at the age of 75 and was inducted into the Cincinnati Jazz Hall of Fame in September. His daughter Zarleen Watts and her mother Caryn Watts keep Schwartz’s Point running these days. Maintaining the building – which is more than a century old – is a labor of love for Watts and her mother, who spend 50-60 hours a week scheduling bands and doing other assorted tasks, all to keep the club alive in memory of Moss.

Before he died, Moss told CityBeat during a rare night off in October 2015 that he was interested in discussing the full extent of his club ownership history in Cincinnati – a legacy he didn’t think had been collected in any one piece of reporting. While Moss believed at the time that Schwartz’s Point would likely be his final club, his reputation as an avant-garde jazz club operator and restaurateur was solidified over the decades prior, earned at locations like Mahogany Hall, the Golden Triangle, Emanon’s and more.

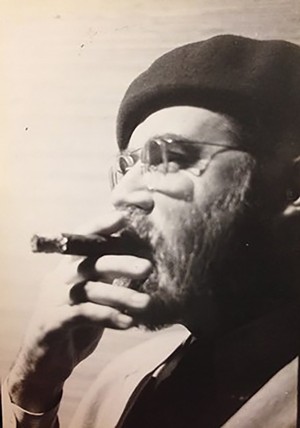

In life, Moss was a tall man with a ponytail, often sporting a black leather vest, thick-rimmed glasses, a beret and a full mustache. He’d been playing jazz and running clubs around Cincinnati since 1965, and he claimed to have started playing the piano as soon as he could reach the keys as a child.

Throughout his lifetime, Moss cultivated a polarizing persona around Cincinnati. Many praised the pianist for playing a central role in the area’s avant-garde music scene, while others found his large ego and opinionated personality too much to handle. Music reporter Cliff Radel captured Moss’ many angles.

“Moss is Cincinnati’s answer to Charles Mingus. He knows only one way to play – his way,” Radel wrote in 1979 for the Cincinnati Enquirer. “He can be extremely difficult to work with. He has fired players on stage. He has screamed others into an early retirement. If he dislikes his playing, he’s been known to walk out in the middle of a solo.”

“Call him what you will, none of these names hurts his playing. Moss is an excellent pianist who sets extremely high standards. What he gives is what you get – the best,” Radel continued.

Sipping fino sherry in a dim corner of Schwartz’s Point in 2015, Moss told CityBeat that he was aware of this split in public opinion and laughed, saying that he thought he had calmed down some in his old age. He fiddled with a couple of cigar butts that lingered in an ashtray to his left, having smoldered out long before, and swirled his sherry thoughtfully.

“Very dry. And just a little more alcohol than a white wine,” Moss said of the drink. “You know, at one time I had three different venues going – had interesting cash flow. I was drinking high-priced cognac, smoking expensive cigars.”

“When jazz was happening in Cincinnati, it was happening,” Moss continued, nodding along to the Society Jazz Orchestra record he had put on in the background. Moss proceeded to reminisce on his musical history and the many clubs he’d run when jazz was “happening” in Cincinnati.

What follows is Moss’ full history in the Queen City as told to CityBeat before he died, with the help of some historical resources and interviews.

Mahogany Hall

The art of improvisation originally drew Moss to jazz music, and Cincinnati’s swingin’ jazz scene in the 1960s was what brought him to the city where he would reside for the majority of his life, he told CityBeat in 2015. Moss originally came to Cincinnati in 1965 from Indiana to help open a business in Mt. Adams called Mahogany Hall, which had a bookstore on the second floor. At the time, the owner wanted to open up a jazz club on the lower level.

“In Mt. Adams alone, there were four big jazz jobs,” Moss said. “They had jazz at least five nights a week. Jazz was thriving. There must have been 25 steady five-night-a-week gigs around Cincinnati. I’m not even counting [that] at that time, every big hotel had a piano player running four or five nights a week.”

The popularity of jazz in the late 1960s through the 1970s was not unique to Cincinnati, though. At that time, faces like Miles Davis, Dizzy Gillespie and John Coltrane were at the height of the scene. Everybody knew the tunes, and the music was in high demand.

“Late ’60s, early ’70s, you could probably work as much as you wanted to. You could work somewhere at cocktail hour, then go somewhere else and play,” Moss said.

Radio station WNOP 740 AM helped tie together Cincinnati’s jazz audience. The station originally was based on Monmouth Street in Newport but eventually moved to broadcasting from three 20,000-gallon, welded-together fuel drums on the Ohio River, commonly referred to as “the Jazz Ark.” Moss attributed much of the local jazz scene’s success to this tiny, floating AM station and its devout following.

“The unique thing that was beautiful about WNOP was you could call them up and talk to somebody. So you could actually tell them what you were doing,” Moss said. “You have a quick change in venue, they could get it on the air that afternoon. That’s gone, now. It’s really a shame.”

The Jazz Ark stopped broadcasting jazz on Dec. 31, 2000, switching instead to Catholic programming.

Love’s Coffee House and the Golden Triangle

While the jazz scene was still in full swing, Moss helped run a number of clubs around Cincinnati. After Mahogany Hall, he and a few partners opened a joint on Calhoun Street called Love’s Coffee House, which played jazz for the height of what Moss described as the “hippy, bell bottom-wearing generation.” Then he opened a club on McMillan Street called the Golden Triangle in the recently-demolished building that later became Mad Frog. Moss stayed there playing jazz for almost 10 years.

During this time, Moss also began indulging in his ambitions to cook – ambitions which would only grow throughout his career. He worked for an organization called Reality Foods, which he described as “a kind of macrobiotic carryout” that supplied baked goods and health food to the Golden Triangle and other places around the city. Here, he and some friends would spend late nights baking before distributing their creations to clients and customers in the morning.

“That was fun. I’d bake – stay up late on Saturday night – and bake this bread, 100 loaves. We’d open at 10 [a.m.], and they’d be gone by noon,” Moss said.

Emanon

After a decade at the Golden Triangle, Moss was ready to try his hand in a new location, opening Jan. 19, 1974.

“We had this place up on Nixon and Jefferson that was an internationally known jazz club called Emanon,” Moss said. “‘No name’ spelled backwards.”

Bob McKay, a writer for Cincinnati Magazine, called this club the best place to hear live jazz in all of Cincinnati in 1978, describing it as being divided into three rooms: a backroom for patrons more interested in dining than in music, a screened-in porch that opened when the weather became warmer, and a front room with a bandstand in which guests were required to refrain from talking during performances.

By all accounts, Moss was very particular about that last point. In 1979, while Moss was still playing at Emanon, Cincinnati Enquirer’s Radel wrote a column titled “The Cat’s Demanding — He’ll Be The First To Tell You So” about Moss’ requirements.

“I expect a fairly attentive audience. I don’t consider my music any less articulate than what the Cincinnati Symphony Orchestra plays. In fact, I consider it far more articulate,” Moss told Radel. “People have no feeling for jazz musicians. They might do six nights a week, four sets a night, with just as much involvement as a concert pianist. Yet, if those cats [concert pianists] play more than two concerts a week, they think they’re in trouble.”

Cincinnati jazz pianist Fred Hersch wrote in his 2017 book Good Things Happen Slowly that Moss and pianist Frank Vincent had two of the most prominent jazz followings in Cincinnati at that point in the late ‘70s. Hersch described Vincent’s crowd as “Oscar Peterson worshippers” and Moss’ crowd as avant-garde. Hersch did not hide his own opinion of Moss, describing him as “a self-absorbed alpha-male cult-leader type.” Regardless, he painted a vivid picture of the atmosphere that surrounded Moss and his scene at this time in his life.

According to Hersch, Moss was a large man with an even larger ego, who sported a beard, a ponytail and a huge collection of hats and drove around town in an early-1960s Cadillac hearse.

“Late at night, when the gigs were over, the staff and the musicians would hang around the Golden Triangle, sipping Turkish coffee or cognac and smoking high-quality hashish till dawn,” Hersch wrote. “There would be fantastic music playing on the stereo, and that’s where I first tuned into Ahmad Jamal and Erroll Garner and got deeply into Monk.”

Hersch wrote that the exposure to the scene that Moss cultivated was very influential for his personal artistic career and grasp of jazz music.

“‘The scene’ was seriously kooky and kookily serious. I much preferred it to the Frank Vincent-Oscar Peterson contingent, despite my discomfort with Moss himself,” Hersch said.

Mozart’s and Ivory’s

Moss’ ambitions as a chef took off following his time at the Golden Triangle and Emanon, and he decided to try his hand at a fine dining establishment. He called it Mozart’s and hoped it would introduce Cincinnati to what he considered upscale Italian cuisine.

“Not the spaghetti and meatballs thing by any stretch, but risottos and things like that,” Moss told CityBeat.

For Cincinnati Magazine, Melanie Barnard wrote in 1980 that the restaurant was located in a small, aged corner building near the University of Cincinnati which was once a streetcar stop. Barnard said that Cincinnatians could find one of the most extensive wine selections in the city there, as well as espresso served from “a gleaming and steaming copper machine.”

After Mozart’s, Moss took a two-and-a-half year hiatus to earn a doctoral degree from the University of Northern Colorado before returning and getting involved in a few other jazz club ventures around Cincinnati. CityBeat celebrated one of them around the time the paper was founded in 1994.

“One of [the jazz club ventures] was way down here on McMicken called Ivory’s. We won best jazz club — or whatever that CityBeat crap is — the year I was there. I just managed the place, but everybody thought I had money in it,” Moss said.

Moss didn’t have money in Ivory’s, but people may have assumed he did. He was the club’s “talent scout, music director, house pianist and cook for Ivory’s free Thursday night exotic dish,” Radel wrote in the Cincinnati Enquirer in 1994.

Schwartz’s Point

Throughout his time at Ivory’s and even before leaving for the University of Northern Colorado in 1990, Moss had begun collecting furniture and decor for his passion project: Schwartz’s Point. He had already bought the striking triangular building on Vine Street back in 1977 out of sheer interest in its unique shape. The Over-the-Rhine structure was built in 1875, and it was formerly a dentist’s office owned by three German immigrants called the Schwartz brothers.

“I think we had the bar here, which is from the original Blue Wisp, actually, on Madison Road. We cut about five feet off,” Moss said.

The Blue Wisp was a popular jazz club and bar where the Blue Wisp Big Band formed. The club no longer exists, but the band can still be heard around Cincinnati.

After returning from Colorado in the 1990s, Moss began hosting Tuesday night parties in the building that would eventually become Schwartz’s Point in 1998. Moss told CityBeat that the parties became so popular he was busted by the authorities and told to attain a liquor license. After doing so, he turned the building into a three-night-a-week jazz club, which officially opened in 2008.

Dominic Marino, a founder of the Northside bar Urban Artifact, performed with Moss at Schwartz’s Point while attending graduate school at the University of Cincinnati. He told CityBeat in 2015 that the gig there was never about the money, but rather a musical experience with no rules.

“It’s one of the few places where I felt completely free to express myself,” Marino said. “It was like being transported into the seedy under-bellies of what the stereotypes of jazz clubs used to be, and I wouldn’t have it any other way.”

Marino said that Moss was an interesting character. And while Moss hadn’t always been the most popular musician around town, Marino called Moss “a real musician” – exhibiting passion and genius on the piano – and remarked that Moss had always done things his own way.

“Ed said I was ‘a real motherfucker’ once,” Marino said. “It’s a moment I hold dear coming from someone like him.”

Jazz isn’t as accessible in Cincinnati as it used to be, but there are still a few places around town to hear it, including the still-open Schwartz’s Point. But the scene has tightened over time, and fewer and fewer gigs for jazz musicians are available each year.

Regardless, Moss kept playing in his dimly lit bar, often greeting guests on nights that he played by welcoming them to what he called his “living room,” which was fitting with him living in the apartment above the club. But jazz clubs today aren’t packed like they were in the days of the Golden Triangle or Emanon, especially not in a small club on a corner of Vine Street.

What ultimately kept Moss playing jazz and trying to sustain a club through all the change?

“Faith,” he told CityBeat. “No, I don’t know, man. I really don’t. Why does a painter paint? Why does a sculptor make things? It seems a part of my organic existence. I hate the legwork of it, but I’m willing to do it for those few hours a week where I get to play.”

Moss said that regardless of the crowd that it drew, Schwartz’s Point was by far his favorite club he’d ever owned. With its triangular design, 1.5-inch horse-hair plaster walls, intimate atmosphere and Moss’ hand-picked players, Schwartz’s Point had everything that fit his idea of a top-notch jazz club.

“And these triangle tables, I actually had made for the Golden Triangle,” Moss said, referencing the many triangular tables throughout the bar. “I had them in storage for years and years. The whole idea was this triangle thing brewing in my mind, probably with this building in mind as a final destination for the situation. On all levels, it works.”

Even in his later years, Moss put a great deal of work into playing jazz three nights a week for however many people showed up to his club that night.

“I want everyone to have a good experience. I don’t mean that in a facetious way. I just want people to come in and go, ‘That was worth it,’” Moss said.

When he wasn’t playing jazz, Moss had a few students that he coached. He said that he tried to have a life of his own outside of his club, but that was difficult while running a business, even one that was only open three nights a week. Moss said that one week, he timed how many hours he put into stocking and preparing the club, coming up with almost 50 hours.

“It’s like a full time job. I hate to admit it, but it really is,” Moss said.

Until his death, Moss played and recorded albums with the band he formed at Emanon back in 1979, The Society Jazz Orchestra. They released the album Further Extensions the year Moss died.

Moss said he always enjoyed having his own space near the heart of Cincinnati where he could experiment and hone his craft.

“It all has ups and downs,” Moss said. “But I think we kind of live for the good nights, where nothing goes wrong, everybody feels like playing and maybe the weather’s OK.”

Schwartz’s Point, 1901 Vine St., Over-the-Rhine. Info: thepointclub.weebly.com.

Coming soon: CityBeat Daily newsletter. We’ll send you a handful of interesting Cincinnati stories every morning. Subscribe now to not miss a thing.

Follow us: Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter