For a long time, Springdale presented the image of a bustling American suburb — Tri-County Mall, filled with stores and shoppers, was an anchor to the community about 20 miles north of Cincinnati. Shopping strips, restaurants and, further out around them, light industry filled the surrounding blocks, punctuated by wide roads filled with traffic streaming in and out of the area.

But on a recent weekend, many parking spaces outside the mall — and the dark, closed-up shops inside — were empty. Traffic was lighter. Some of the big box stores have moved locations or pulled out of the area entirely.

People still live and work in Springdale, of course, and some areas still have the same suburban bustle, humming with shopping supercenters or industry. But the makeup of parts of the city and some surrounding areas has been changing. And as demographics shift in places where cars have long ruled, dependence on sparse public transportation options looks likely to grow.

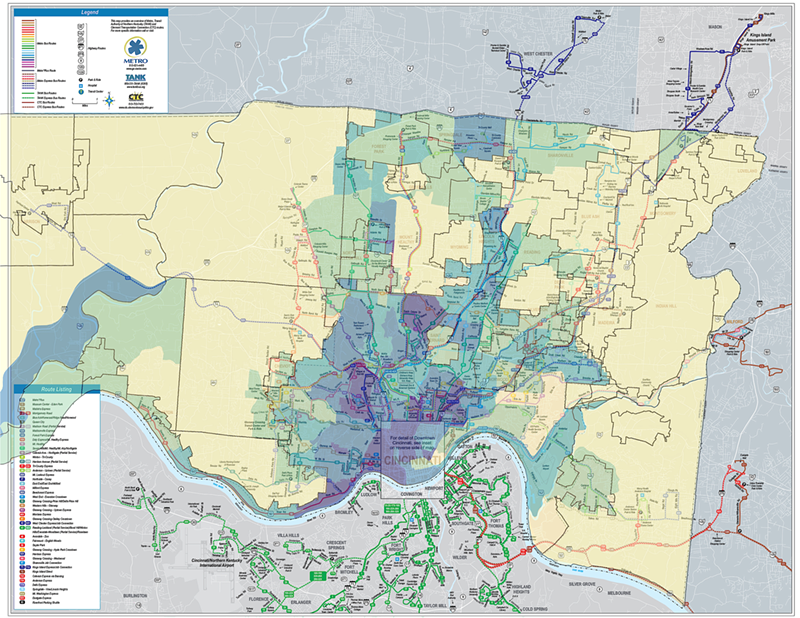

A glance at a map of routes run by the Southwest Ohio Regional Transit Authority’s Metro bus service shows routes are scarce or non-existent in some places with deepening pockets of poverty. The upshot: Folks who are already struggling with low incomes — and who may not own a reliable vehicle — face an added barrier to accessing jobs, health care and other necessities even as they live in places that are more sprawling and less connected.

Swaths of Forest Park, Springdale, Lincoln Heights, Lockland, Mount Healthy and areas in the far western part of Hamilton County are well below the county’s median household income and have larger portions of their populations in poverty, but have few or no bus routes running through them.

Just a few minutes’ drive from the mall in neighboring Forest Park, a Nepali and Indian grocery has filled a space once occupied by a chain drug store. Tiendas, taquerias and small grocery stores, their signs in Spanish, have sprouted along the secondary streets, filling older strip malls.

As these areas’ populations have diversified, so too have their economic makeups. Immigrants struggling to make a better life in the United States, those who can’t afford rising prices closer to the city and other economically vulnerable people have all increasingly begun to call places like Springdale home. The poverty rate here was 18.8 percent in 2016 — almost three points higher than the county’s and 10 points higher than it was in 2000.

That year, Springdale was about 68 percent white, 26 percent black and 4 percent Hispanic, roughly comparable to the composition of Hamilton County as a whole.

By 2016, however, Springdale was 41 percent white, 35 percent black and 17 percent Hispanic.

Those minority populations have median household incomes $15,000 to $20,000 lower than their white counterparts in Springdale, Census data shows. They also have worse health outcomes. The average age of death for a black or Hispanic person in Springdale is nine years lower — about 68 years old — than it is for white residents, who die on average at 77 years old, according to data from the Springdale Health Department.

There are a number of reasons for that divide, but difficult or non-existent access to health care, healthy food, good-paying jobs and other necessities play a role.

Various parts of Springdale are served by three routes — the 78, the 20 and the 23x. But those routes are often low-frequency and many low-income pockets of the city aren’t near bus stops at all.The lack of transit options is a public health issue, Springdale Public Health Commissioner Matthew Clayton says. That's why he's been reaching out to elected officials, other public health professionals and community groups across Hamilton County to find ways to expand transit options for Springdale and other communities outside the urban core.

“If you look at areas of poverty, we have people who are going to live a shorter life span, they’re going to encounter preventable disease, have daily struggles with the stresses of poverty,” he says. “We want to concentrate efforts where need exists. Transportation as a social or structural barrier to access to health care, fresh food, to economic opportunities, to social networks — those are big issues. If we were to look at a map of infant mortality in Hamilton County, I think we would find that it aligns with poverty, and with opportunities to improve public transportation.”

The disconnect between transit options and jobs is well-documented. A study published this year by the University of Minnesota’s Accessibility Observatory found that only about 10 percent of jobs in the Tri-State area are reachable via a one-hour commute via public transit. And a 2015 study of Metro’s reach commissioned by the Cincinnati USA Regional Chamber, the Urban Land Institute and other organizations found that only 23 percent of jobs in Greater Cincinnati are reachable by public transit within 90 minutes.

So far, Clayton says he’s gotten at least some response about his efforts to find funding for expanded transit options from the City of Cincinnati Health Department, the Hamilton County Health Commission and Metro.

He’s also heard good feedback from Hamilton County Commission President Todd Portune.

Clayton isn’t the only one calling for better bus service, of course. Transit activists with the Better Bus Coalition have pushed the issue to the forefront in Cincinnati, leading the city to new initiatives such as the city’s first bus-only lane.

Those victories come as a heavy debate rages about the future of Metro. The bus service faces a huge, $184 million deficit over the next decade if new funding doesn’t materialize.

And that’s just to keep the status quo. An independent report released by consultants AECOM last January found Metro would need at least $1 billion in upgrades over the next 10 years to make it more functional and get more county residents to the region’s jobs.

Metro, which provided 15 million rides last year, has already started reductions and restructuring of several routes to save money. Service on Routes 1, 28, 29x, 32, and 49 was reduced in various ways starting late last year.

The bus system’s budget this year relies on some $56 million from the city’s transit fund, which has paid for buses since 1973 with a .3 percent city earnings tax. The bulk of the rest of the money will come from bus fares ($18.9 million) and federal sources ($11.5 million). Ohio ranks 45th among states when it comes to public dollars per capita spent on transit, even though it ranks 14th in ridership. In 2015, Ohio, the nation’s seventh-most populous state, spent just 63 cents per person on public transit. In contrast, every other one of the nation’s 10 most-populous states spent dollars, not cents, per person.

Last year, SORTA got just $800,000 from the state of Ohio. Making the situation more difficult, Hamilton County as a government doesn’t pay for transit. Cuyahoga, Franklin and six other Ohio counties pitch in for their transit authorities.

There was a window to change that earlier this year, when SORTA’s board mulled a Hamilton County tax levy that could have addressed the bus service’s looming deficit and even funded significant expansions.

With a .6 percent or .8 percent sales tax increase, Metro says it could provide a number of upgrades, including 24-hour service on major routes and extensions of some routes further into the county. But SORTA’s board opted against the levy, in part after opposition from Portune. The county appoints many members of the transit authority’s board, which will consider the levy again next May.

Portune is instead promoting a plan for a regional bus system that would encompass three states, eight counties and more than 200 local governments. He says doing anything less is kicking the can down the road, but his critics — including transit activists looking for quicker improvements — say riders can’t wait the years it will take to get the complex plan off the ground.

Springdale Public Health Commissioner Clayton says he’s well aware of Metro’s financial realities.

“I’m not out to beat up on Metro,” he says. “I get they’re dealing with a fiscal crisis and they have a heavy financial burden. But increased options for public transportation in these places would be significant for people there."

He’s investigating grants and other funding sources that could help pay for expanded service. He also says he’ll be in meetings with Hamilton County elected officials and other groups as he continues to push for better public transit access.

“I’m very much looking forward to working with them and finding ways to advocate for increasing public transportation options in areas where those services are truly meaningful,” he says. “If we want to move the needle, it has to be an all-hands-on-deck approach. We need to have the interest of the general public at heart. It really will bring a lot of benefit.”