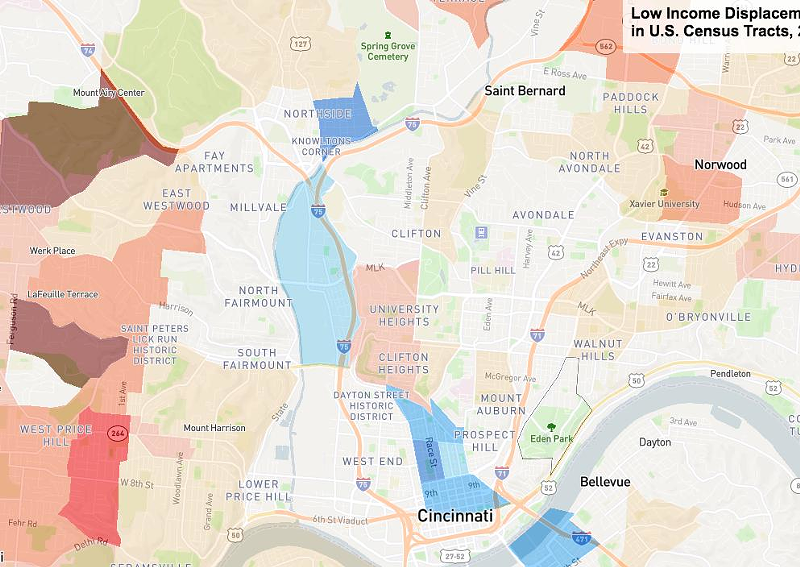

Concentrated poverty is increasing in a number of areas in Greater Cincinnati, new research suggests, while a few Cincinnati neighborhoods have seen a significant outflow of low-income residents, many of them people of color, and an influx of wealthier residents.

Those changes are complex, but roughly seem to follow a pattern: There are increasing concentrations of poverty in outlying neighborhoods and suburbs.

A recent study from the University of Minnesota Law School's Institute on Metropolitan Opportunity looks at patterns of displacement and concentrated poverty in Census tracts across the country from 2000 to 2016. It shows some broad patterns by using data from the U.S Census Bureau — but there are some big caveats to think about when looking through its findings.

The research shows that in many neighborhoods and suburbs outside central Cincinnati, poverty has grown dramatically in the past decade and a half.

For example, one Census tract in Mt. Airy saw more than 1,000 higher-income people move out and more than 3,500 low-income residents move in, raising its percentage of low income residents from 26 percent to 55 percent.

The study defines low-income as someone making less than 200 percent of the federal poverty level — about $23,760 for a single person in 2016.

Another tract in West Price Hill that was hit hard by the 2008 financial crisis saw more than 1,600 higher-income residents leave between 2000 and 2016. Meanwhile, almost 3,000 low-income residents moved in. Neighboring tracts, including the tract just to the west, also saw a big increase in low-income residents and a significant exodus of higher-income ones.

That pattern repeats in some places outside the city. One tract in Sharonville saw 1,050 more low-income residents move into the neighborhood and more than 500 middle-to-high-income residents move out. Its share of low-income population went from 17 percent to almost 38 percent. The neighboring tract to the west saw an even more dramatic change — low-income residents went from about 28 percent of the population to 51 percent.

Even though geographic patterns are changing, some underlying racial inequities are not. While suburbs that are high-performing economically saw an influx of about 1,400 new black residents across the region, most black residents moving to suburbs (almost 26,000) went to places that the study categorized as experiencing strong economic decline. Residents of Hispanic origin saw a similar trend. About 1,600 went to high-performing suburbs, while 17,000 went to suburbs in strong economic decline.

Those economically high-performing suburbs saw about 11,000 new white residents, while the suburbs that are seeing strong economic decline saw an incredible 78,000 white residents leave.

Those demographic shifts can have a number of consequences, experts say, some of which CityBeat has explored in past stories.

Meanwhile, a few Cincinnati neighborhoods have seen another dynamic entirely: loss of a significant number of low-income residents and an influx of higher-income newcomers.

The four Census tracts that make up Over-the-Rhine saw 635 more middle-to-high-income residents move in between 2000 and 2016, while as many as 3,000 low-income residents moved out over time. The neighborhood is still predominantly low income, though by a much lower margin.

Another tract encompassing downtown lost 361 low-income people while gaining 418 middle-to-high-income residents. And a tract encompassing a popular part of Northside saw roughly 1,500 low-income people leave as 199 higher-income people moved in.

The authors of the study calls tracts like this "displacement tracts." But it isn't entirely possible to know why residents left a neighborhood.

OTR is a good example. The study considers data from 2000 and compares it to data from 2016, but a number of events happened in between those years, including the 2001 civil unrest and the 2008 financial crisis, that could have compelled residents to move elsewhere. The neighborhood's total population dropped somewhat during the years considered.

The study doesn't consider trends in median rents in Census tracts or other data, so it's hard, looking at its results alone, to know why population change happened.

That said, the study's findings are consistent with a 2017 analysis by CityBeat finding that a number of low-income, predominantly black residents left the neighborhood during a more specific time period between 2010 and 2016, as rents rose and development of higher-end business and residential projects boomed in the neighborhood.

A study by Xavier’s Community Building Institute using Census data and real estate listings found that even as middle and high-income housing has increased, the most affordable housing — units costing about $400 for a one bedroom — in OTR decreased by 73 percent from 2000 to 2015, going from 3,235 units to just 869.

OTR has also seen a decrease in residents living in the neighborhood who receive rental help from HUD attached to Section 8 vouchers. With vouchers, HUD picks up the cost of rent above 30 percent of a recipient’s income for any private residence that accepts them. At its peak, in 2004, 545 voucher holders lived in OTR. By 2015, that number had dropped to 326, according to HUD data.

The neighborhood saw 405 mortgages between 2013 and 2017, federal data shows. Of those, only 12 went to black home buyers. In 2017, the median income of borrowers seeking loans in the neighborhood was $147,000 — up from $80,000 in 2013 in a neighborhood with a median household income of about $15,000 a year as of the 2010 Census.

There are other areas where the research isn't fine-grained enough to capture displacement that is in fact happening for economic reasons. Because the study only considers displacement as an aggregate outflow of low-income residents in relation to a net gain of higher-income residents, it misses neighborhoods where more complex dynamics are happening.

For example, CityBeat in 2018 documented the displacement of several households whose rental homes were being redeveloped in an increasingly-popular corner of Walnut Hills. Many of the residents in those homes were unable to find affordable housing in the neighborhood and ended up in Northern Kentucky or West Side neighborhoods experiencing concentrating poverty.

During the scope of the study, however, that tract in Walnut Hills lost both low- and high-income residents, meaning it was not considered to be experiencing displacement.

The study also likely doesn't capture other kinds of displacement that can occur due to the expansion of major institutions like universities and hospitals, which sometimes cause loss of low- and moderate-income housing without adding permanent higher-income residents.

College students, for example, often count as low-income residents in Census counts, even though they often aren't permanent residents of a neighborhood and may sometimes have economic realities different than other low-income individuals and families. The University of Minnesota study counts Census tracts in Corryville, Fairview and University Heights as experiencing concentrated poverty, but, as Twitter user Cole Weirich points out, much of that is likely related to students.

In Walnut Hills and other neighborhoods, coming demographic change may be too early in the process to show up in the study. That, too, may be accelerated by contexts unique to those neighborhoods.

The West End Census tract that will host FC Cincinnati's coming stadium, for example, saw the loss of more than 700 low-income people during the study's timeframe and a loss of more than 400 black residents. During the same time, a handful of higher-income residents moved in. The neighborhood is still predominantly low-income, and there isn't any evidence those two numbers are related. But the coming stadium is sure to heat up a real estate market that was already on the upswing.

In 2012, there were 16 home improvement or mortgage loans written in the three full Census tracts that make up the West End, according to federal data. In a neighborhood that is 85 percent black with a median household income of about $13,000 a year, the $2,124,000 in loans went to applicants with a median income of $58,000 a year. Only three of the recipients were black.

By 2017, the last year for which federal data is available, there were 41 such loans worth $5,554,000 sold to applicants with a median income of $80,000 a year. Thirteen of the recipients of those loans — about 30 percent — were black.

Meanwhile, funding for new affordable housing projects in the West End has lagged. The neighborhood’s last allocation of Low Income Housing Tax Credits — which fund the development of much of America’s low-income, non-Section 8 housing — was $972,000 for the Sands Senior Apartments in 2014.

Overall, the University of Minnesota study shows a demographic change happening in the city limits. Black residents left many of the city's neighborhoods, regardless of economic performance.

Neighborhoods in the city experiencing any level of economic expansion lost more than 6,000 black residents during the years the study considers, while lower-performing neighborhoods lost about a third of that.

Meanwhile, whites left those lower-performing neighborhoods in large numbers — but more than 2,000 moved into high-performing city neighborhoods.