This story is featured in CityBeat's Oct. 18 print edition.

When I began research for a story about a death doula, I set out to uncover and deliver information much like any other story. Find an expert, dig into their experience and report what I found out. Although I’d never heard the term death doula — sometimes called end-of-life doula — before, I assumed it was like a birth doula but reversed.

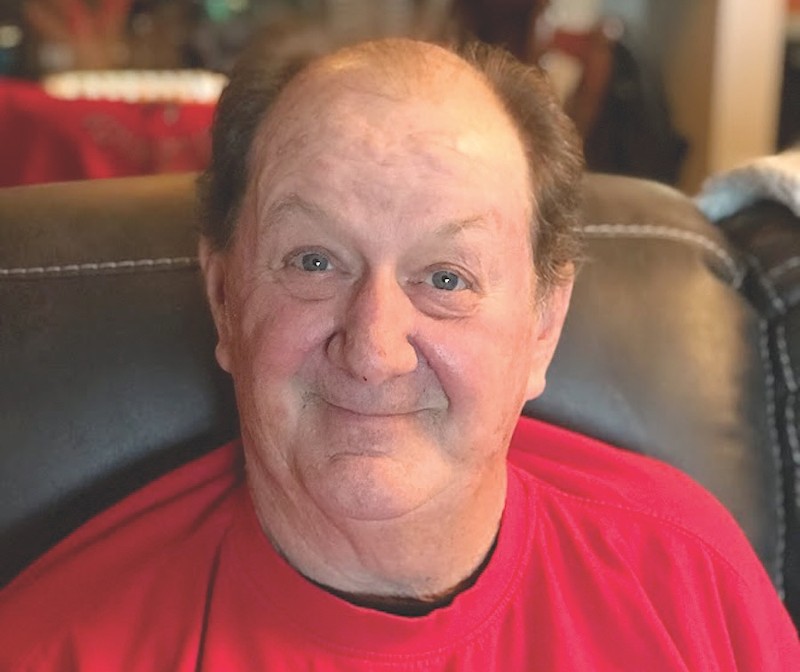

I discovered a local death doula, George Ziegler, and he verified my assumption. Ziegler has been providing end-of-life guidance and support to families and dying people through his business Essential Dignity for four years. He was certified through the National End-of-Life Doula Alliance, though life experience had provided the best training, he says, after losing 10 friends and family members over a three-year period and enduring a near-death experience of his own.

“An end-of-life doula is simply a support person,” Ziegler tells CityBeat. “We provide non-medical, holistic, nonjudgmental support to those nearing the end of life. We typically offer support to the family and friends of the elderly, dying or recently dead. An end-of-life doula educates and empowers individuals to make choices on their own end-of-life care and final burial or funeral.”

You can find a death doula in Cincinnati or elsewhere simply by Googling the phrase. Surprisingly, there are options. Hospice of Cincinnati launched a volunteer death doula program this year and Jen Blalock owns and operates Death Doula Cincinnati, LLC. There is also a Death Doula Collective that provides a nationwide directory of death doulas, including options in Ohio.

It’s up to a loved one or a dying person to hire or request a doula themselves. The prices for a death doula service vary depending on the professional and some — like Ziegler — offer services free of charge in certain circumstances.

As an advocate for the dying, Ziegler explains, a death doula’s responsibilities vary. They are a liaison between the dying and family members, doctors, nurses, etc. They provide company to those who don’t want to be alone and advocate for the dying person's needs, rights and options, whether that be where the person wishes to have their final moments or how to make them most comfortable. A death doula can also be an aid to a family’s practical and emotional needs at the time.

When I reached out to Ziegler, he was instructing a class for the University of Cincinnati’s Professional and Continuing Education program called “A Good Death.” He invited me to join the final installment of the class, which was an hour-and-a-half lecture/discussion that changed my mind about how I wanted to frame my findings.

In short, the class was gently triggering. The raw discussion and sincere questions threw me into a reflective state that urged me to allow a memory I’d been suppressing to resurface. The open dialogue in the class felt more like a support group than a classroom and I realized that it was helping others heal or prepare or understand. I realized I was skipping a step on my own path to heal from losing my stepdad, the only dad I ever knew.

I realized during the class that sharing can be therapeutic and remembering is painful but helpful. Shared experience is powerful and necessary. And death, after all, is the most inevitable shared human experience that exists.

My stepdad, William VandenEynden, died in February 2022. My family had just celebrated his 70th birthday and a positive note from the doctor about his kidney health. We went to one of his favorite places, the casino, where he always won and knew exactly when to walk away.

Everyone called him Bill. He served our country and loved golf, fishing, his dogs, sports and his family. He was a jokester, king of dad jokes and would quote Family Guy or one of our favorite movies, Bruce Almighty, constantly. He was a retired mailman and worked for the U.S. Postal Service for many years. On days when I would wake up early enough to catch him before he went to work, he’d rise from his beloved spot on the couch, scratch his stubbly chin and say, “Time to move America,” with pride.

The thing that sticks with me about that statement, which I can still hear him say, is that America never stops moving. We lost the head of our family and during and after the fact, the phone still rang, emails still poured in, cars zoomed by and the responsibilities that burden a family after losing a loved one loomed.

If I had known death doulas existed at the time, I would have suggested the resource to my mom, sisters and brother-in-law.

“I am an aid to both [families and dying individuals],” Ziegler says. “The needs are different for the dying person and the loved ones. It is such a … stressful time. People can be overwhelmed with the circumstances. Each needs support in a completely different way — I provide the support to both.”

We didn’t lose our father in an instant; it happened gradually, becoming more apparent yet more unbelievable each day. We were nearing “a new level of powerlessness,” as Ziegler puts it, explaining why it’s so impossible to deal with death.

As I remember it, Bill was in the hospital for almost a month before he passed. Somewhere in that time, he nearly died from complications of an emergency surgery, which left him breathing through a ventilator in the intensive care unit. On top of it all, it was during the COVID-19 pandemic. Because of pandemic restrictions, we didn’t get the chance to visit with him until his final few days, and that will never be okay with me.

To have someone like a death doula, a clear-headed resource, to consult during these times might have made the experience more digestible. Looking back, it would have been helpful to know what to expect when we finally got to walk into that ICU room. What is he going to look like? Can he hear us? Should I bring him his favorite flannel? Favorite book? What should we not do or say?

“The Bengals are going to win the Super Bowl! Can you believe it?” was the first thing we said to him (wishfully thinking) right after a million “I love you’s.” The news played in the background and showed the Bengals getting off of a plane to compete in a playoff game. He raised his eyebrows in excitement. Most of the time, he wore soft expressions unbroken by sound or touch. I could tell he was happy we were there, but he couldn’t speak or open his eyes for more than a blink.

“In the cases where I've been with people who are not verbal, I still talk to the person, even though they're not responding, I still talk to them,” Ziegler says. “And so the communication is still flowing. And then also, maybe a little bit more like rubbing their head or rubbing their arm or just kind of loving on them. I really believe that when we do that with people who are dying, I think it goes much further than we realize.”

Every beep of a machine and rustle in the hallway was unsettling. The room was dull and sterile. I was thankful that all six of us could fit in there without feeling claustrophobic. As Ziegler would put it, we were “emotionally whacked” and didn’t have time to think about ways to improve the atmosphere or create a sacred space for Bill’s final days. These are things doulas think of for you — they suggest it and communicate with the dying person and loved ones about how to make it an optimal experience.

“I don’t like when I see sterile settings and environments,” Ziegler says. “I like to ask the dying person directly, what do you want regarding colors, smells, music, welcome visitors and visitors who may not be welcome? This may also include artwork, paintings and pictures. As simple as this sounds, it sometimes gets forgotten in the intensity of the circumstances.”

Smells. Who thinks of that? Not a family trying to prepare themselves for the worst. Intense is an understatement. But when it comes to these situations, the right words don’t even seem to exist.

It was so unbearably hot. We had to cover ourselves from head to toe in plastic hospital garb on account of COVID restrictions. If we stepped away for a phone call, fresh air or the bathroom, we had to re-do the whole process of dressing up in terrible plastic coverings, even gloves.

And then it came time to unplug the machines. I didn’t think I'd wish for those random beeps to return. I wasn’t prepared for the silence — or a world without Bill in it. The doctor, who was very kind and comforting, sat with my family in the waiting room. She explained that from here on out, there was no telling if it would be hours, days or weeks.

How is this going to play out? I worried. I tried not to cry. I tried to stay composed in the room with him. We held his hands, patted his cheeks with a cool, wet towel. We took turns telling him that we loved him, recounting precious memories aloud.

“If you’re ever with someone who seems like they are completely out of it, the hearing is usually the last thing to go,” Ziegler says. “So they are laying there hearing everything. They can totally hear you. Just know that. Assume they can hear everything you're saying. The good in that is getting close to that person and being able to whisper in their ear, ‘I love you,’ or whatever you want them to hear.”

How long do we have? The thought repeated. What do we say now? Do we still talk about the Bengals? Keep it light? It all seemed irrelevant and all I wanted to do was wake up to a world in which this wasn’t happening. I couldn’t think about anything else — everything was slow and felt like a trudge. A chore. Breathing, eating, sleeping, communicating with loved ones, friends and work.

What I didn’t wonder was, how will dying look? What will it sound like? Which of us has the emotional strength to process all of this after the fact? How long does grief last? When will life feel light again?

“All too often, people just don't know. They're not told what to expect,” Ziegler says of watching someone in their final moments. “And so what I try to tell people as delicately as I can, is here's some of the different things that could happen. And sometimes it's that the person will seem like they're fighting; they're struggling, maybe like they're suffering or fighting. Sometimes people go very peacefully. But there's other times where the body will kind of, it almost seems like they're fighting it and it’s hard to watch. But it's better to let people know that and also let them know sometimes why that's happening. It might look like the person is suffering, but that’s not always the case. Maybe their muscles or their nerves are what's causing the reaction that you're seeing, so they're not suffering. But it's still, it's just important to let people know, here's what to kind of expect. Because when no one tells us that, it can be horrifying.”

We only had hours. None of us would return to the hospital in shifts, like we planned, so he wouldn’t be alone. There isn’t a way the situation could have played out that would have felt like it was “the right way.” The weeks after, however, could have come easier.

Everyone has to learn the shape of their own grief, the weight of it. We have to learn how to hold it, where to store it. If we don’t, it drags us; it gets to lead our lives and emotions. But no one should have to make funeral arrangements for their spouse or write their father’s obituary without guidance — or at all, though there’s no easy solution for the latter.

“In many cases we don’t deal with this until the circumstances of end of life are upon us,” Ziegler says. “At this point, there is a bit of a scramble to find pertinent information. Along with the scramble, the loved ones may also be emotionally knocked off their feet. A part of them may have a hard time even staying present and able to stay in the moment.”

In the delicate moments after death, doulas can remain with loved ones and family members should they request it, Ziegler says. This support can manifest however the person needs, whether it be advice on how to make arrangements, how to communicate with others on the very fresh topic, how to grieve and how to communicate with lawyers, doctors, funeral directors, etc., Ziegler says.

“Absolutely after people die, I'm available,” he tells CityBeat. “A big part of what I want to do is help people with grieving and all the practical stuff that needs to happen. It's like, I'm in your corner. So any tough conversations with doctors or attorneys, I'm right in there with them to help encourage them or help them if need be.”

There is no cure for grief. In my experience, it’s something we can learn to live with rather than waste energy wishing away. There aren’t words or gestures that make losing a loved one easier but there is art and music and the sun and other people to ease the transition to normalcy.

Most importantly, there’s human connection. Whether that kind of support comes from a loved one or a doula, it's invaluable. Ziegler is working to hold more space for those who want to learn about death, caregiving or aging and how to approach it. Essential Dignity is one avenue for that work, as well as his class at UC.

“I am constantly trying to create spaces where we can have dialogue on aging, caregiving and death,” Ziegler says. “They are such important topics and, in my opinion, we don’t talk about these topics enough. I had heard many positive things about UC and their Communiversity program. I thought this would be one more place to continue this dialogue and I’m so grateful for the opportunity.”

It is a privilege to age. With time comes experience and wisdom. And sometimes the most wisdom is earned through the toughest experience. Death is a part of being alive and talking about it, while sensitive and difficult, should not be taboo. Collectively, we can only help each other through compassion, understanding and sharing our human experience.

For more information about death doulas or upcoming classes and events by Ziegler, visit essentialdignity.com.

Follow us: Apple News | Google News | NewsBreak | Reddit | Instagram | Facebook | Twitter | Or sign up for our RSS Feed